Want Your Customers to Save More? Use Behavioral Economics

How many times a month do you think about saving? Are you one of those who have proactively chosen an optimal savings mechanism (e.g., a retirement or index fund) or are you like the majority of us who don’t save nearly enough and think of regular savings as a goal for the distant future? The psychology that influences your own behavior — a discipline called behavioral economics, which draws insights from psychology and economics — may not be very different from one that influences a low-income individual living in the urban center of Dar-es-Salaam or in rural parts of Tanzania.

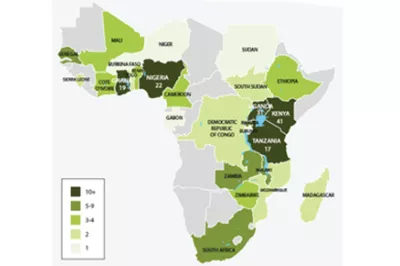

Tanzania is unique in many ways. Although mobile money got a later start in Tanzania than it did in neighboring Kenya, today more than 50 percent of the country's adult population is registered for formal digital financial services, mostly mobile money. As mentioned in our earlier post, Tanzania is also the first country in Sub-Saharan Africa to allow mobile money providers to earn interest on their escrow accounts, with Tigo-Pesa being the first to offer its subscribers interest payouts of 7 to 9 percent per annum (better than a one-year term deposit). Despite these incentives, however, average mobile savings balances remain low, especially among low-income users.

This raises some important questions: Are behavioral economics at play here? Are behavioral inertia or biases guiding people’s decisions? And if so, can solutions derived from behavioral economics move them beyond these biases, resulting in greater use of digital financial services? To help answer these questions, CGAP partnered with the World Bank’s Mind, Behavior, and Development Unit (eMBeD), Financial Sector Deepening Tanzania (FSDT), Busara Center for Behavioral Economics and Airtel Money Tanzania on a savings study. First, using behavioral economics, we set out to understand what influenced the saving habits of low-income Tanzanians. Then we conducted experiments to see what impact targeted messaging interventions could have on those behaviors.

Through our initial research we found four dominant behavioral themes that influenced which savings mechanisms people used:

- Mental accounting. Tanzanians, like most people, use mental shortcuts to build associations between their preferred savings mechanism and their reason for saving. Often, this means putting savings into different places or accounts based on criteria like the source or purpose of the money (e.g., saving money for business expenses in a small jar while saving for school fees in a community box at the local savings and credit cooperative).

- Agency. Agency refers to whether people feel like a product gives them control over some aspect of their lives. The Tanzanians we spoke with wanted products that gave them control over their financial lives.

- Trust and risk. Interestingly, there was no savings medium that respondents considered to be universally “most trustworthy.” Some considered banks trustworthy, while others trusted mobile money or their local savings group lock-boxes. People expressed trust in whichever savings mechanism they used most actively.

- Social influences. Social norms, networks and trends also influence Tanzanians’ savings behavior and the channels they use to save.

Of the two primary experiments we conducted, the first was a messaging experiment, where participants interacted with an SMS system for 14 days. Participants with similar profiles were divided into five groups. A control group received no messages from the platform, while the other four groups experienced an SMS treatment grounded in the behavioral themes identified above. The first group received generic messages that reminded them to save. The second group received messages tailored around the psychology of agency and control. The third group's messages were tailored around mental accounting, while the fourth group received messages that inform them of how much super-savers in the group had already saved.

One of the approaches was clearly the most effective. The group that received SMS messages about the savings balances of other savers saved at a higher rate than the control group. Interestingly, the group that received messages about agency saved even less than the control group did, implying that the wrong message can be worse than no message at all. In any case, the implications of the social influence treatment are striking: a message that compares savings to that of slightly better savers can increase saving by up to 11 percent (for details, see this slide deck).

Our second experiment dug deeper into the behavioral theme of trust and risk. Respondents trusted whichever savings medium they used most actively. This suggests that their choice of savings product might not always reflect their true preferences but rather the product information that was most readily available to them. This experiment aimed to answer two questions: Which common features of savings products do customers value most? And if asked to select from an array of products with different features, will customers choose products that have the features they say are important to them (i.e., optimal products)?

First, participants were presented with a list of eight savings features — security, privacy, convenience, accessibility, fees, interest, check balance and language — and were asked to rank the attractiveness of these features. The rankings were used to create three pairs of savings products (a total of six products) for each participant. Each pair included one optimal choice, based on the participant’s rankings, and one suboptimal choice. Participants were shown each pair of products and asked to choose one product per pair that they would like to use. We found that although having more choices at their fingertips engaged the participants, it often resulted in cognitive overload and suboptimal product choices.

Interestingly, one attribute — privacy — emerged as a clear winner in these experiments; security was the least preferred attribute. This suggests that although digital products are typically marketed as secure, security might not be the attribute that appeals to the greatest number of people. It also means that customers’ choice of savings vehicle, and their trust, may depend on their perception of how risky that vehicle is in terms of confidentiality.

As these results suggest, financial services providers who are looking to encourage savings among low-income customers should take a closer look at socially influenced messaging. Such messages have strong potential to positively impact savings behavior. Additionally, since people tend to make suboptimal choices when presented with too many features, providers should make information on confidentiality simple and clear so that customers can easily choose the most private savings vehicles.

More generally, providers that are looking to build a strong customer base with healthy financial behaviors should apply the principles of behavioral economics.

Add new comment