4 Cyber Attacks that Threaten Financial Inclusion

Few experiences undermine a digital financial services (DFS) customer’s finances and trust in DFS like becoming the victim of a cybercrime. This is especially true of low-income customers, who are least able to rebound from the losses, and of the newly banked, whose trust in financial services may be fragile. Unfortunately, cybercrime is a growing problem in developing countries, where customers often conduct financial transactions over unsecure mobile phones and transmission lines that are not designed to protect communications. In Africa, the number of successful attacks against the financial sector doubled in 2017, with the biggest losses hitting the mobile financial services sector. But which threats pose the greatest risk today?

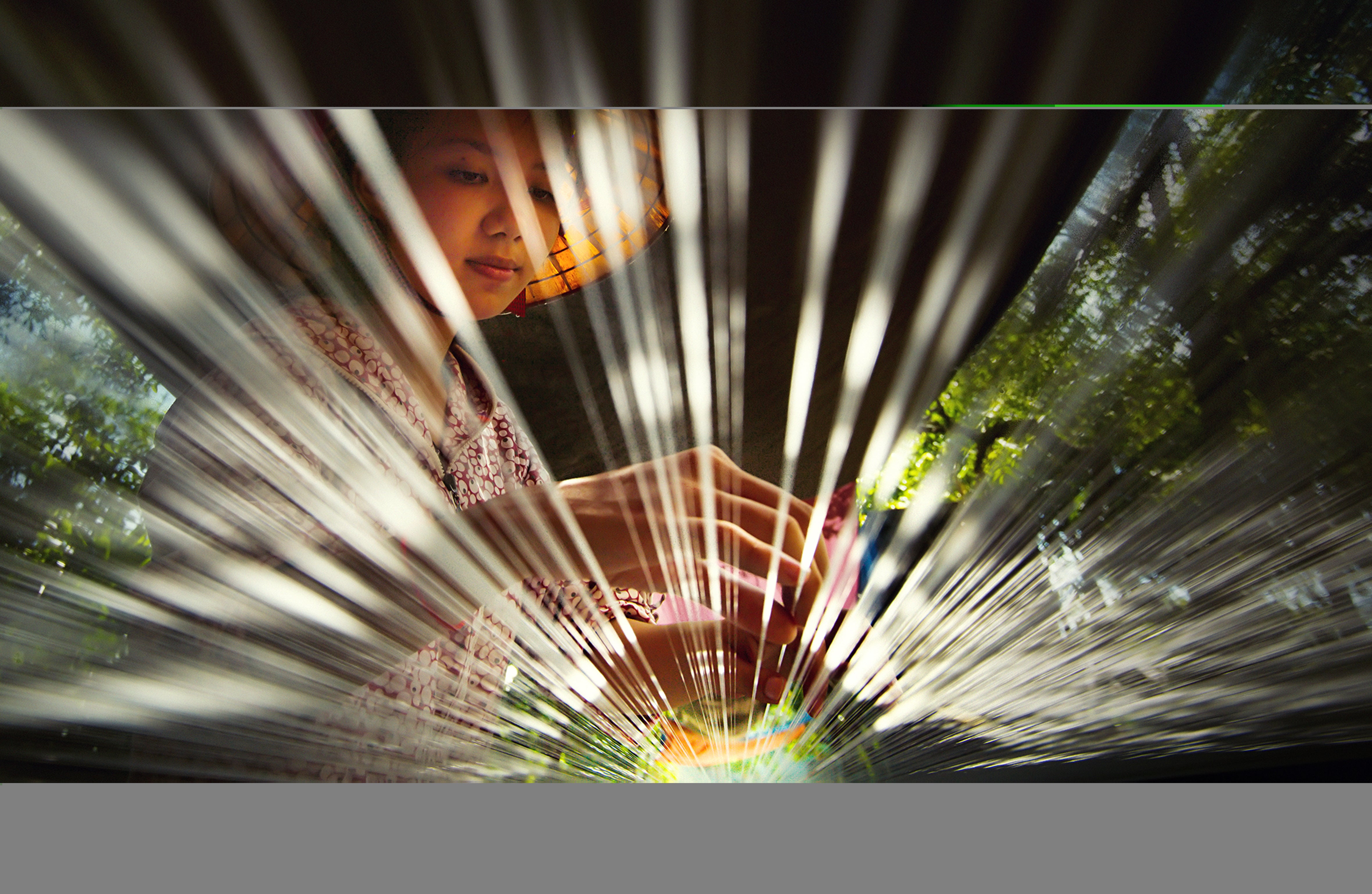

Vietnamese farmer

Vietnamese farmer

In 2017, CGAP surveyed 11 DFS providers operating in Africa to understand how they perceive and mitigate cyber risks. We learned that all of them have been affected by cybersecurity incidents and are at various stages of implementing cybersecurity measures in their organizations. While they are still most concerned about better-known types of fraud in DFS, such as malicious employees and agents, they are seeing themselves confronted with four types of risks emerging in cyberspace.

1. Social engineering

In a social engineering attack, the criminal tricks the victim into revealing sensitive information or downloading malware, which opens the doors to physical locations, systems or networks. The idea is to exploit a vulnerable person rather than a vulnerable system. DFS providers from Ghana, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia told us that fraudsters had duped their employees into sharing their user login details and then accessed corporate information systems. Most DFS providers consider careless or unaware employees to be a major factor in their organization’s cyber risk exposure. But DFS customers are a vulnerability, too. The newly banked are more likely to fall victim to this type of scheme because of their limited experience with digital fraud.

Providers can guard against social engineering through regular awareness and education campaigns. It is also important to appropriately manage user access rights, introduce system log monitoring processes and require two individuals for completing sensitive transactions (i.e., maker-checker controls).

2. Data breaches

Using malware or social engineering, hackers can gain access to valuable information, such as credit card numbers, customer personal identification numbers, login credentials and government-issued identifiers. Weak patch management, legacy systems and poor system log monitoring were cited as the main reasons why DFS providers' systems are susceptible to hacking attacks. In addition to financial losses that can result from a data breach, providers’ reputation and customers’ trust are at risk. In 2017, thieves breached a DFS provider's systems in Kenya and stole hundreds of customers’ identities. The fraudsters accessed sensitive customer information, such as account types and last transactions, which allowed them to pass as legitimate customers and apply for loans in the victim’s name.

To protect against data breaches, DFS providers need to regularly update their systems and software, patch their systems, use strong encryption for data at rest and in transit and implement 24/7 system log monitoring.

3. System outages and denial of service attacks

DFS providers sometimes experience system outages during routine system upgrades or patches. Earlier this year, an upgrade gone awry left DFS users in Zimbabwe without access to their digital money for two days. Systems unavailability can also be the result of a cyberattack. For example, in 2017, M-Shwari customers in Kenya were left without access to their savings and loan products for five days. And, after the outage, several found inconsistencies in their account balances. The most frequent form of attacks that cause system unavailability are denial-of-service attacks. In a denial-of-service attack, cyber criminals overwhelm a server by flooding it with simultaneous access requests, depriving legitimate users of access to the system. In most cases, the objective is to harm the business. Yet, in some cases, cyber criminals have launched denial-of-service attacks to distract attention from an attempt to gain access to the system.

Effective countermeasures include continuous network traffic monitoring to identify and detect attacks while allowing legitimate traffic to reach its destination, a solid and tested incident response plan that allows for quick reaction in an emergency and strong change management processes and disaster recovery planning.

4. Third-party threats

DFS providers rely on third parties for a range of services, such as mobile network, information technology and data storage solutions. Sometimes, these providers misuse their system rights to access confidential customer information that they can sell or use for social engineering. Also, a third party that handles sensitive information may not have appropriate safeguards against cyberattacks, putting at risk the confidentiality and integrity of the DFS provider’s customer data.

To address third-party threats, DFS providers should implement due diligence reviews of current and potential partners, including reviews of their security policies and practices.

Impact on low-income customers

If physical money used to be kept safe in bank vaults, what is protecting money now that it is digital? This is a financial inclusion question because the answer is especially important for low-income customers. In developed countries, it is usually the financial services provider that is legally responsible for bearing the cost of fraud. In developing countries, it is often the customer. The experience of fraud and rumors of fraud experienced by others causes mistrust in DFS, especially among lower-income consumers. The DFS providers we spoke with in Africa recognize their need to invest more in cybersecurity for both themselves and their customers. They acknowledge that better safeguards are needed to mitigate threats and be better prepared to respond to incidents. Failure to take the relevant steps could deter people from entering the formal financial system and significantly harm consumers and markets.

Comments

Dear Silvia, Thank you for…

Dear Silvia,

Thank you for your excellent article, it is great to see that CGAP is now starting to address the challenges of cyber security, following World Bank, IMF, ECB and many others worldwide, but for financial inclusion, which is a track not so much frequented until now. Your observations are very close to what we have noted in Africa.

The fact is that the rapid development of Digital Financial Services in the sector is exponentially increasing the cyber risks; the question is no more if the risk will become material, but more when, at what frequency, and at what cost. And the costs are more and more in the million euro range, and rising. The key lesson we get observing losses in banks, central banks in the last years is that there is a shift from stealing data to stealing money from institutions and customers, in a context where most often deposits are not guaranteed. This means that widening Customer Protection programs is now required, to include customers and institutions in one dimension, data and money in the other dimension. A large awareness effort is necessary for boards, employees, customers, as well as technical and financial partners of financial inclusion.

In Africa, only 14 countries or so on the 54 countries of the continent have a national cyber security centre, and only a handful is really in operation for private and financial sector. Little help is to be expected from that side, at least in the next years.

Additional financial regulation may help at some extent, although experience has demonstrated in more advanced countries that related costs may be very high, probably not bearable by most financial inclusion actors, that it may take many years to achieve, and that it is far from being sufficient given the skills of external and internal hackers, you have now to put your hands in the engine and supervise your systems on 24x7.

Individual approaches may be tempted by largest actors e.g. MNOs, but they are expensive, lack the access to international cyber intelligence networks (CERT Computer Emergency Response Teams) that are necessary to prevent, detect, respond to and recover from attacks efficiently, and in many cases miss the necessary skills to succeed.

That would leave little place for hope to improve cyber resilience for financial inclusion, unless we start thinking as a community of interest, not as individual institutions or countries. The fraud scheme or the hack your competitor is suffering today, you will suffer tomorrow. The great achievements that have been permitted in the telecom industry by the GSMA global Fraud and Security forums may pave us the road. Financial Inclusion may not have the same financial and technical resources as Telcos, for sure, but regional or continental consortiums will make the best use of the money.

That is what we have been building in West Africa in the last three years, we will be happy to share our practical experience and get feedbacks from the community.

You can contact me at jlperrier at suricatesolutions dot com

Add new comment