Bridging the Humanitarian and Development Divide

At a recent Center for Global Development and IRC event celebrating the launch of their joint publication “Refugee Compacts: Addressing the Crisis of Protracted Displacement,” I was struck by the concluding remarks of IRC’s CEO, David Milliband, that one of the key actions necessary to bridge the humanitarian and development divide was to shift more humanitarian aid to cash. He noted IRC’s commitment to delivering 25 percent of its aid through cash by 2020, a significant increase from the current 6 percent for all humanitarian aid. This commitment mirrors other shifts in policy by leading humanitarian organizations, such as the 30 organizations that have signed up for the Grand Bargain. The Grand Bargain calls for increasing cash-based aid and for other important steps to improve the impact of humanitarian assistance.

The increasing use of cash is one important step in the right direction. Evidence shows that cash is more impactful on the lives of the poor than in-kind assistance, giving people with low incomes greater choice in their spending and improving the efficiency of the transfers themselves. The move to cash should be leveraged, but in and of itself it will not be sufficient to fully bridge the humanitarian development divide.

In CGAP’s latest paper, “The Role of Financial Services in Humanitarian Crisis,” we argue that embedding financial inclusion as a stated outcome in humanitarian aid will result in better results for poor people. We offer several important examples of how applying a financial inclusion lens to humanitarian aid can yield a win-win for all actors involved — aid agencies, countries and the impacted populations. Examples include:

Cash transfers as an entry to long-term access to financial services. Today, most benefits of switching to cash accrue to aid agencies in the form of greater efficiency and reduced leakage. Since agencies typically give physical cash or vouchers to recipients, they are not encouraging people to open accounts. This is a missed opportunity for financial inclusion. By linking humanitarian payments to accounts, such as mobile money accounts, we can open up the channels for people to receive remittances through social networks and family when future needs arise. There is ample evidence, cited in the CGAP paper, that remittances help sustain people impacted by crisis and that countries where mobile money is already active see increased remittance flows during periods of crisis. Using humanitarian cash transfers as a mechanism to help poor people open and use accounts presents a compelling opportunity to link crisis response to people’s longer-term development needs.

Cash transfers as an opportunity to build payment infrastructure. Humanitarian actors are using a growing number of out-of-the-box payment solutions (i.e., temporary digital solutions) to facilitate fast and efficient disbursement of cash transfers. While these initiatives are useful in that they allow for quick disbursement, they mostly focus on improving the disbursement process itself rather than the outcomes for the recipients or the country impacted by crisis. If aid agencies look for meaningful ways to leverage and extend the existing payment infrastructure in a country, the benefits of their humanitarian investments are likely to far exceed the short-term gains of a closed-loop system. First, expanding the infrastructure will enable connectivity for local communities. Second, this approach provides an opportunity for the private sector to participate in the crisis response process. Third, solutions that provide benefits for both displaced populations and host communities are likely to be more appealing to government actors, who are often managing tensions around limited resources between these two groups.

Using a financial inclusion lens is not always a quick win, but we know crises situations are increasingly longer term in nature and that adapting responses to longer-term approaches is commensurate with this new reality.

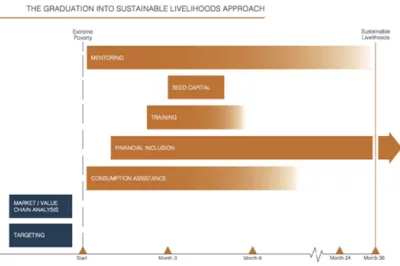

Beyond cash transfers, there is a growing need for humanitarian actors to integrate durable solutions for crisis-affected people to sustain their livelihoods. This is typically seen as the purview of development actors, but given the longer periods of displacement today, addressing people’s livelihoods is clearly another important nexus between humanitarian aid and development. Many aid agencies are already doing this. UNHCR is embedding the graduation approach as part of its Global Strategy for Livelihoods 2014–2018. NGOs like IRC and Mercy Corps also focus heavily on integrating livelihoods programming into their work. While mainstream financial services actors have done some work in crisis markets, there is limited evidence regarding the impact of their work on crisis-affected people. The CGAP-World Bank Group paper identifies a need for more experimentation and evidence on how all types of financial services (credit, savings, insurance, and payments) can support the livelihoods of crisis-affected people. This will likely require more collaboration between traditional humanitarian practitioners and financial services organizations.

There is undoubtedly great momentum to strengthen the humanitarian and development nexus. We hope CGAP’s paper will be useful to practitioners, donors and policymakers as they look for ways they can contribute to this important effort.

Add new comment