Climate-Focused G2P: Beyond Disaster Response

Climate-focused government-to-person payments that are made as part of a social protection program can increase their recipient's capacity to prepare for, cope with, and adapt to the effects of climate change - including losses from rapid-onset disasters as well as the impacts of slow-onset events.

Between 32 million and 132 million people may fall into poverty due to climate change. For reference, that figure is similar in magnitude to the devastating economic impacts of COVID-19, which caused between 71 and 100 million people to fall into extreme poverty. Slow-onset climate change events are likely to undermine poverty reduction efforts and increase the demand for social support globally. Gradual environmental changes such as desertification, sea level rise, and loss of biodiversity are key drivers of multidimensional poverty and social marginalization. Yet most social safety nets are predominantly focused on losses from climate extremes and disasters rather than longer-term adaptation. There is a need to link such programs with comprehensive climate risk management policies and consider long-term adaptation in their design.

How does climate change affect those experiencing poverty?

Slow-onset climate change will displace large numbers of people. The poorest areas – which also happen to be the most climate-vulnerable – will be hardest hit. People will migrate from less viable areas with lower water availability and crop productivity and from areas affected by rising sea levels and storm surges.

Those living in poverty have greater exposure to climate risks and fewer coping mechanisms. Climate plays a role in most of the shocks that keep or bring households into poverty — notably, natural disasters, which the poor suffer disproportionately from. According to the World Bank, people experiencing poverty have greater exposure to drought and high temperatures, and to flooding in cities. For example, when Cyclone Sidr struck Bangladesh in 2007, the most affected districts were those with the highest population density and poverty rates in the country.

How can social safety nets help people facing poverty adapt to climate change?

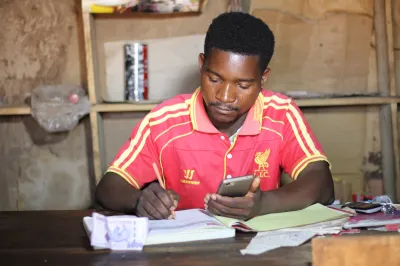

Social protection programs are a useful vehicle for climate change adaptation because of their large existing coverage of the poor – those most vulnerable to climate change. The average level of social safety net coverage of the poorest globally across 96 countries is 56%. Moreover, there is a global commitment to increasing the coverage of these programs under the UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 1 on ending poverty. Target 1.3 states, “Implement nationally appropriate social protection systems and measures for all, including floors, and by 2030 achieve substantial coverage of the poor and the vulnerable.” Social safety net programs reduce poverty. From the available household survey data, it is estimated that 36% of people escape absolute poverty because of receiving a social safety net transfer. Small but predictable flows of cash to the most vulnerable recipients improve their strategic livelihood choices and stimulate productive investments. Well-established program delivery mechanisms can be used to deliver regular payments, extra payments for adaptation activities, and emergency payments in response to a climate disaster.

Social protection programs’ response to climate change adaptation can be placed along a continuum. However, most social safety nets do not build the long-term adaptive capacity of their recipients (see Figure 1), with most making insignificant or unintentional impacts.

Figure 1: Climate change adaptation continuum for social safety nets

-1) Negative impact

Some programs may have a negative impact on their recipients’ adaptation to climate change. For example, social safety nets targeting those living in natural disaster-prone areas can create a perverse incentive to stay and invest in locations threatened by long-term environmental degradation.

(0) Insignificant impact

A large proportion of social safety schemes have no impact or an insignificant impact on their recipients’ adaptation to climate change. These programs are either too small in scale to have a significant impact or poorly designed and implemented, and as such, are unable to deliver on their core poverty reduction objective.

(1) Unintentional impact

These are programs that support their poor recipients through the delivery of a well-designed and implemented program that effectively reduces poverty but without deliberate climate change adaptation objectives. The value of these poverty reducing programs should not be underestimated.

(2) Disaster-focused

These programs have an explicit focus on disasters including natural disasters such as storms, floods, and drought as seen, for example, in the 4Ps in the Philippines and HSNP in Kenya. These programs are able to disburse emergency payments to recipients and in some case increase their reach to new recipients.

(3) Explicit climate change adaptation focus

Programs with an explicit climate change adaptation focus most typically achieve this through public works which both build community assets and provide cash transfers in the form of wages, both of which can support climate change adaptation as seen in the PSNP in Ethiopia and MGNREGS in India.

Overlaps between social protection, climate change, and disaster risk management

Using social protection programs to address climate change adaptation is not a straightforward proposition because poverty and vulnerability to climate change are complex multidimensional problems. Climate change and poverty combine to amplify the impacts of shocks. Social protection programs are of interest because they aggregate the poor and vulnerable, making targeting them with new climate adaptation interventions both easier and cheaper.

IPCC 2022 states that “Integrating climate adaptation into social protection programs, including cash transfers and public works programs, is highly feasible and increases resilience to climate change.” Implementation of this vision requires three sectors, with different frameworks, approaches, and language, to work together – social protection, climate change, and disaster risk management.

Many existing social protection schemes make transfers to support recipients’ ability to meet their daily needs and may help them prepare for climate-related hazards. However, the current focus on emergency response is insufficient to support long-term climate change adaptation. Consideration may be given to disclosing climate change vulnerabilities to scheme recipients supporting migration to more sustainable areas and better-supporting livelihood diversification. The specific needs of women and girls in disasters and long-term adaptation to climate change also need to be understood and addressed.

Our next blog post in this series will highlight the significant learnings on climate change adaptation from social safety nets in the Philippines, Kenya, Ethiopia, and India. Our last blog will consider supporting women to adapt to climate change through social safety nets.

Add new comment