Exclusion Costs: Financial Inclusion in the Arab World

The Arab Spring leaves no doubt: financial exclusion costs. Arab policy makers, who long regarded microfinance as charity for the poor, are realizing that a financial system that serves only 20 percent of the population is a key ingredient in the recipe for political instability. For too long, positive aggregate growth figures were hiding the underlying causes of the unrest: unemployment, high inflation, authoritarian rule and a lack of economic opportunities for the majority of the population, especially younger generations. It is within this context that CGAP, GIZ and Sanabel co-sponsored the Arab Policy Forum on Financial Inclusion in Cairo in mid-May. In her keynote address at this Forum, Ms. Lobna Helal, Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Egypt, stated that the Arab Spring was above all an expression of discontent with economic conditions and inequalities.

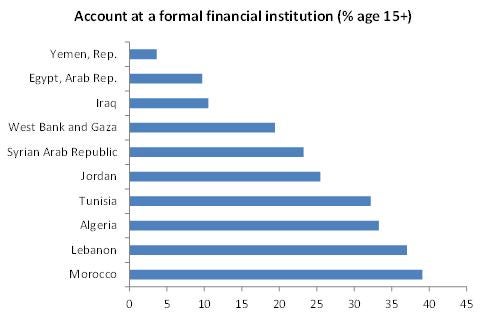

Indeed, economic and financial inclusion in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region lags behind other parts of the world. According to the global financial inclusion survey (Findex), MENA ranks last in regional comparison on financial inclusion. On average, only 18 percent of adults have an account with a formal financial institution compared to a global average of 50 percent (41 percent in developing countries). Only 5 percent of adults in the Arab World have received a loan in the past year. At the same time, working age youth comprise one third of the Arab World, and one quarter is unemployed. Given demographic prospects, that means that countries in the MENA region need to create 80 million jobs in 15 years.

With the Arab Spring, the spotlight has turned to the large segments of the populations that have been financially excluded: micro and small entrepreneurs, rural populations, and young people. There is a need to increase outreach and offer a broader range of services that match the needs of these segments. With the rise in Islamic political parties, there is also an increased call for Shari’a compliant products, which until today only represent a marginal share of overall microfinance portfolios. Several countries are looking at branchless banking as a possible solution to overcome access barriers such as high costs and lack of retail infrastructure, but regulatory reforms are needed to make this happen. At the same time, financial service providers struggle to operate in still unstable economic and political environments.

This transition period in the Arab World offers an opportunity for deep-rooted reforms, now that there is a strong public demand for more inclusive growth. Participants of the Arab Policy Forum identified “non-conducive legal and regulatory frameworks” as the main challenge for financial inclusion in Arab countries. For example, few countries allow NGO microfinance institutions to transform into fully-fledged microfinance banks that could offer savings services. Forum Participants see a clear mandate for governments and central banks to support financial inclusion.

However, the question for many in the forum was whether the newly elected governments across the region will share a common vision of sustainable access to finance for all. Charity-driven microfinance alone is not likely to meet the needs of the currently excluded, which represent a large majority of the population in many Arab countries (see chart). Sustainable financial inclusion Arab policy makers identified a need for awareness raising, a high level commitment to financial inclusion, coordination around a common framework and better metrics to measure progress and identify gaps.

The MENA region has a long way to go towards financial inclusion, but an important step – a change of perception in policy makers – is taking place.

Comments

Expression of discontent with

Expression of discontent with the economic condition and inequalities has been identified as root cause of Arab spring as stated.Further for challenging these issues , ‘ broad range of services that match the needs of these identified segments have been prudently highlighted .However, given the task and its complexities, does mere ‘financial inclusion’(what ever means -branch or branch less )in terms of opening account or availing micro credit alone adequate for accomplishing the said task?

In this context, two issues merit attention of the concerned people for addressing them towards reduction of the exclusion cost

1. Evidences in developing countries such as in Indian and Bangladesh , suggest that even after intensive financial inclusion, there is an exclusion phenomenon by the included ones in terms of ‘ defunct a/c , inoperative account , drop outs, closure of a/c (more pronounced in group system).

2. In the context of regional disparity in economic growth with in any country for that matter, Financial inclusion will not work without adequate regional economic infrastructural development(roads, power, communication, bridges, transport, marketing etc) for ensuring enabling environs for productive functioning of the financial products and services.

Here prudential sequencing the development efforts assumes importance other wise exclusion cost issue cannot be effective challenged.

Dr Rengarajan

Add new comment