Facing Climate Events in Nigeria, Farmers Left With Scarce Options

Ummi squinted in the bright sun in June 2021, wondering whether the rains would even come this year. In this rural area of Nigeria’s Kano state, the rains usually come in March. Last year, they came in April – not late enough to do damage, thankfully. This year, though, with rains three months late, 75% of Ummi’s cassava plants had already died.

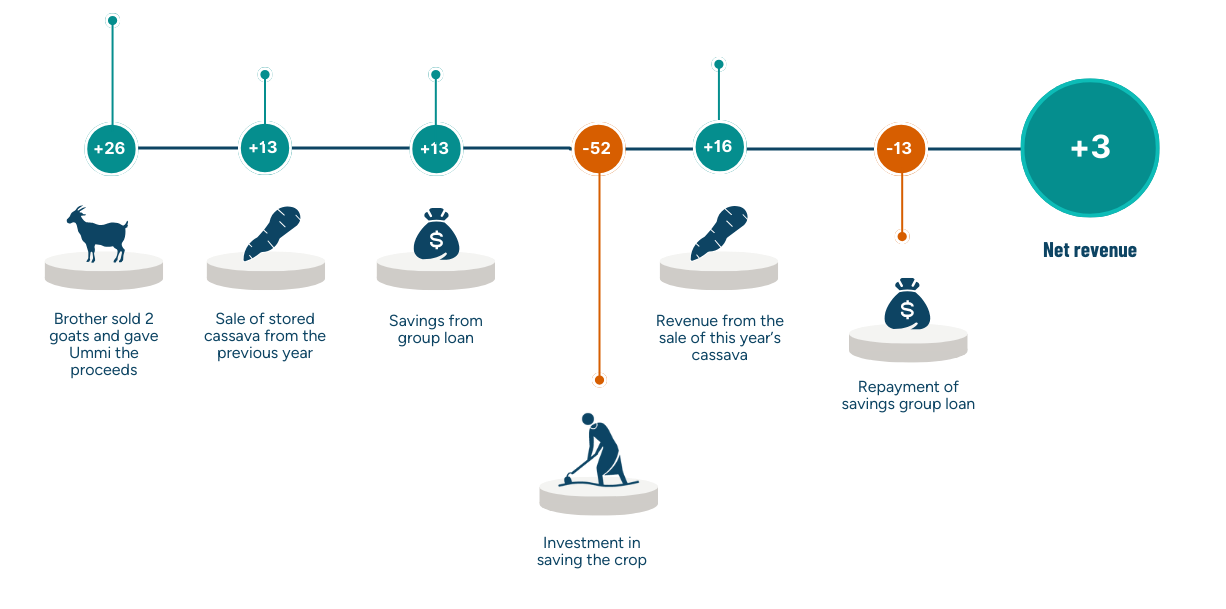

This was despite her multiple efforts to save the crop: hiring labor to bring water from a far-away well, shaping the soil to maximize water flow, and laying down manure to retain that water. Luckily, Ummi had stored a small amount of her crop from the previous year, but to pay for these efforts she also needed a gift of two goats from her brother which she sold, and a loan from a local savings group. The quarter of her crop that survived only fetched 4% of her usual income, so in the end, she made barely anything in net revenue.

Ummi’s cash flow and eventual earnings (in USD)

Ummi also worried about her own 10 goats. Already, the heat had diminished their desire to eat, and they were getting thin. Worse, she worried that their weakened state would make them more susceptible to parasites and bloating from suddenly eating lush grass when the rains did come. She also knew she needed to reinforce their shelter, but had little money left after trying to save her cassava crop. In the end, she sold two goats to reinforce the shelter, but still lost half of the remaining eight goats.

Ummi’s experience is but one of a sample of 250 farmers in northern Kano and southeastern Enugu—two of the most populous states in Nigeria—interviewed for a CGAP-commissioned study to better understand how people experiencing poverty prepare for, cope with, and adapt to climate shocks and stresses – and what role financial services played in supporting them.

Our interviews with Ummi and others highlighted three key implications of climate events for household use of financial services.

Financial strategies play a role even where formal financial options are sparse

In the rural areas of Nigeria where we did our research, formal financial services were limited to urban bank branches and mobile money transfers. Though they were in the minority, those using formal financial services, particularly saving in bank accounts, were able to better mitigate the extreme losses so many of their neighbors suffered. For example, the few cassava farmers who could fund the expensive but effective solution of renting a water pump experienced the smallest declines in income. Of those who rented a water pump, more than 50% used at least some bank savings to garner enough funds to do so. Nonetheless, this was not the strategy used by most farmers we spoke with.

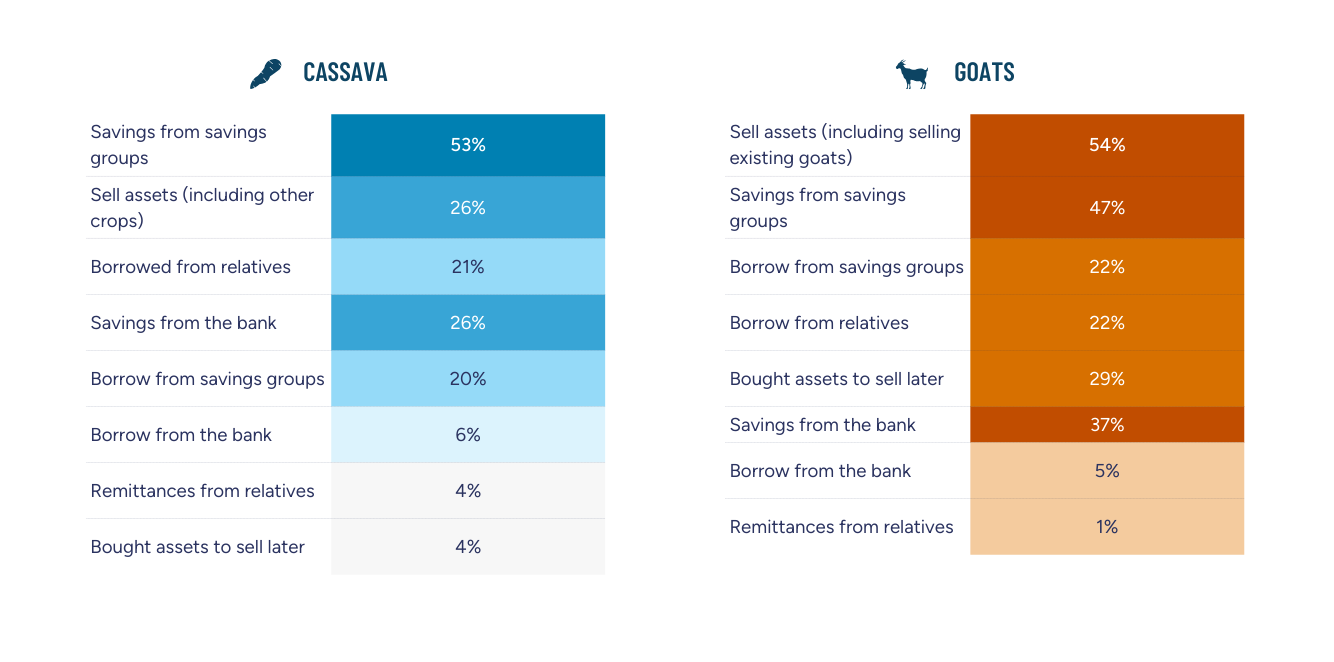

Far more farmers relied on informal financial services to respond to shocks. Most people relied on their own savings and assets before borrowing money, worrying that they would need to repay a loan even in the likely event that they would not have a good crop. Selling assets was an important strategy, but it was easier for goat herders than cassava farmers. Remittances played a strikingly small role.

Financial tools used to fund coping strategies for cassava and goats

That is not to say these services were sufficient. The people we spoke to were happy with how quickly they could access savings group loans, but not with the size of the loans. Moreover, informal savings groups are not always reliable. In both Kano and Enugu, some savings groups failed because many members struggled to contribute during difficult periods. Bank loans were larger and more reliable, but slow — by the time they were approved, crops had already died. Storing crops to sell later was risky since strong rains could cause them to rot. Assets sales were effective but came with a clear feeling of setback.

The cumulative impact of consecutive climate shocks can be devastating, as each depletes the financial options for responding to the next

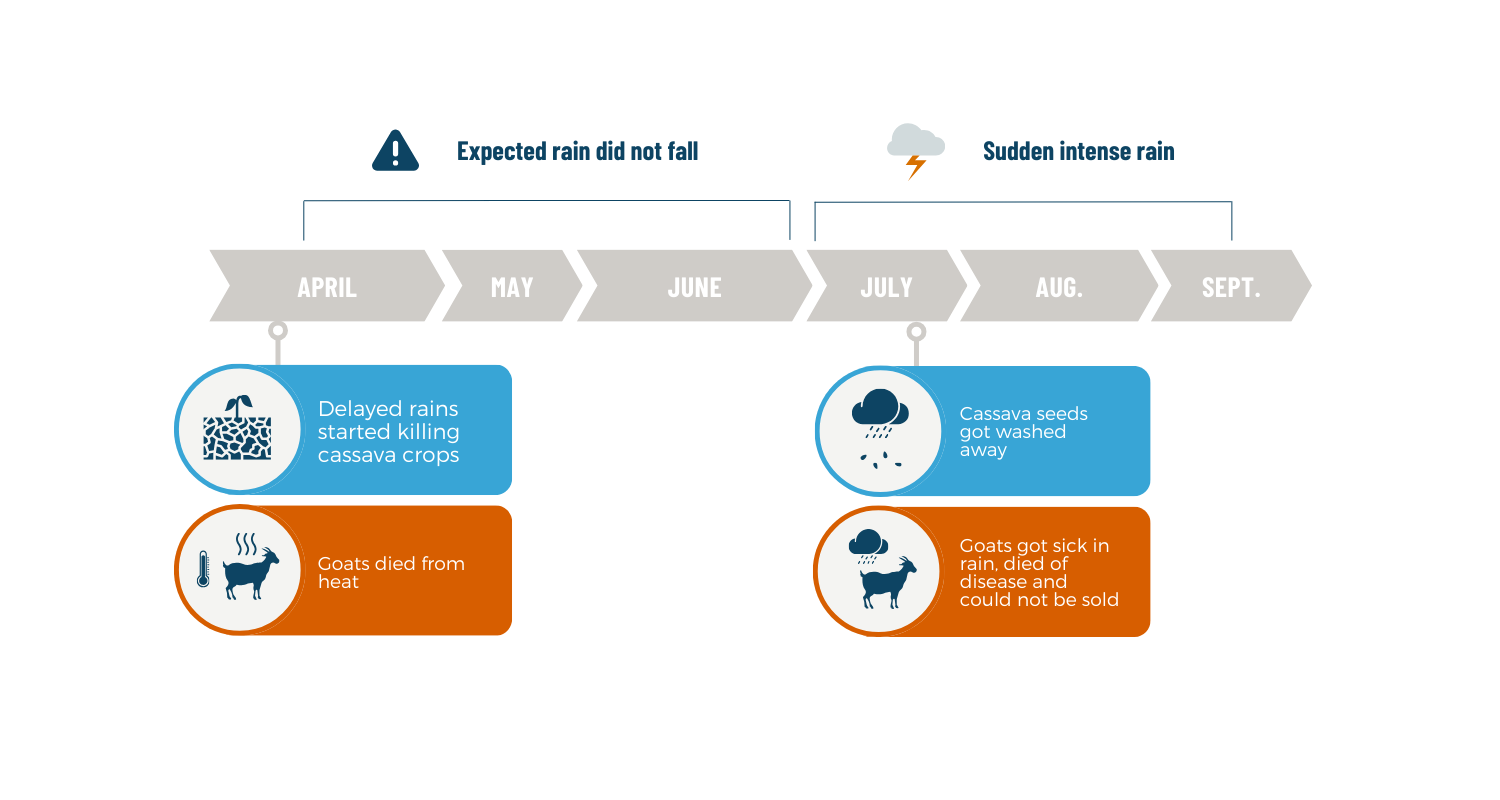

A single drought or flood rarely impacted people as much as a one-two punch of consecutive shocks within several months. The rains came three months late, prolonging the dry season, and then poured all at once, causing flooding and washing away seeds as the dry, hard soil could not absorb all the water. Our research focused on this sequence of shocks for two important livelihoods: cassava and goats.

Timeline of weather events in Kano and Enugu states, Nigeria

The actions that households take to withstand this type of double-barreled sequence of weather shocks can range from free (such as moving earth to efficiently channel water) to expensive (such as renting a water pump). Both the cost and the success of these strategies have direct implications for the available resources and options to respond to the next shock.

Asset depletion over time can severely undermine longer-term climate resilience

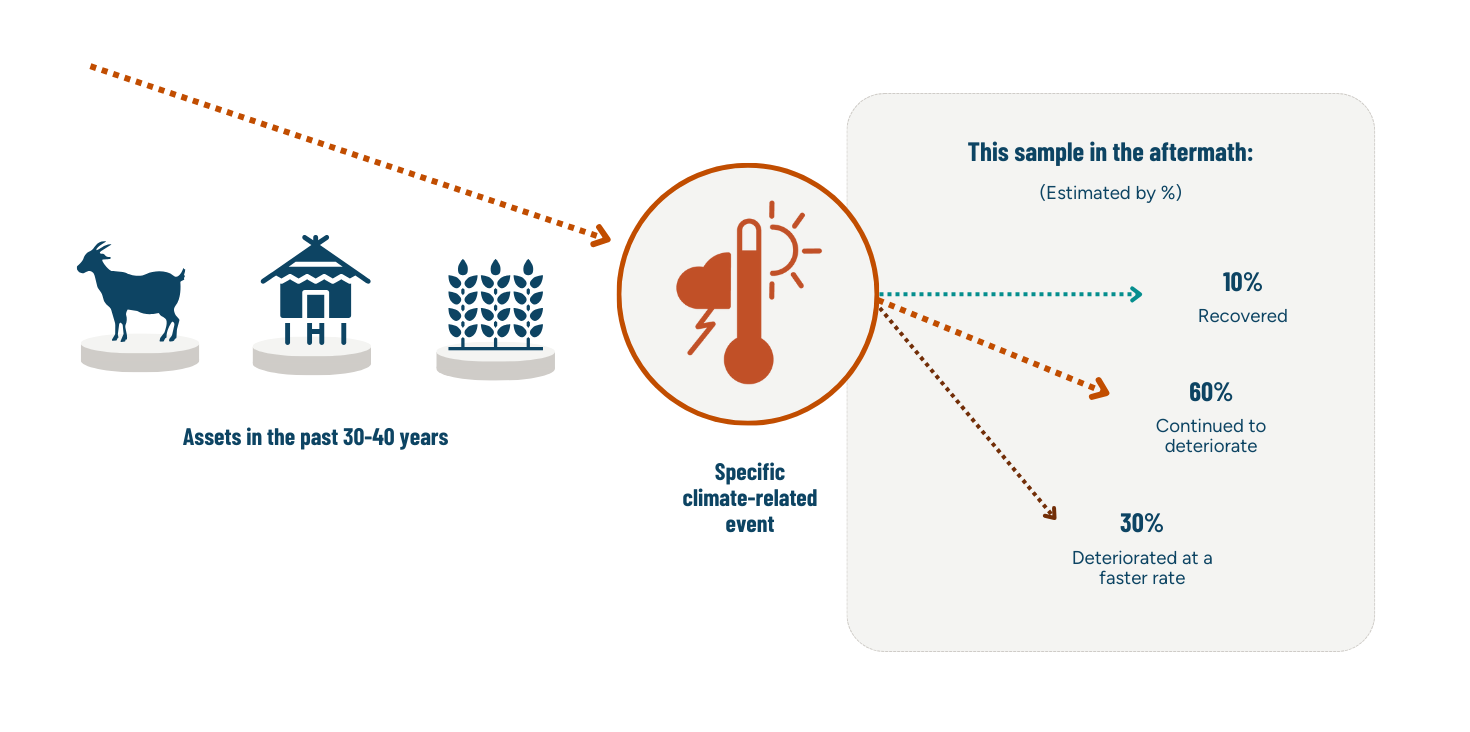

These dynamics of weakening through consecutive shocks fed into and amplified longer-term asset depletion described by respondents in both states, including falling crop yields, lower consumption, higher pressure for multiple incomes, children being taken out of school, and the need to sell central assets such as land and livestock.

The longer-term trajectory this points to for people in these areas and their livelihoods is worrying. As climate shocks grow in both frequency and severity, the resources available to low-income households for managing them have steadily declined. According to the 250 people we spoke to, only around 10% were able to fully recover after the 2021 season, while 90% said their asset base continued to deteriorate. Nearly a third indicated that the 2021 climate shocks had accelerated that deterioration (see figure below).

Impact of a climate event on decades of asset decline in two regions of Nigeria

These findings illustrate not only the importance of financial solutions in supporting climate resilience but the implications when those solutions are lacking (particularly when accumulated across consecutive shocks). Most importantly, they demonstrate the worrying longer-term consequences of insufficient resilience and the need for more fundamental adaptation to climate change. Our next blog will consider what adaptation looks like in practice and what is needed from the financial system to make it work.

This three-blog series shares findings from research by CGAP along with Decodis and MSC on how people living in poverty in Nigeria and Bangladesh are preparing for, coping with, and adapting to climate shocks, and what role financial services are playing in supporting them. The first outlines how households in Nigeria are using financial services in responding to climate events, while the second considers the complexities of locally-led adaptation, and the third explores how financial systems can better support climate adaptation.

Add new comment