Findex and G2P: Are Transfers Translating to Inclusion at Scale?

Governments are enrolling the unbanked into the formal financial system at scale in developing countries, primarily to facilitate government-to-person (G2P) payments. According to the recently released 2021 Findex, roughly 865 million individuals have opened their first account to receive money from the government, about half of them women. While governments send several types of payments, including public sector wages and pensions, the type of transfers Findex measures (payments for educational or medical expenses, unemployment benefits, subsidy payments or any kind of social benefits) disproportionately target the poorest 40% of the population and beg the question, do all these accounts with funds flowing into them amount to financial inclusion?

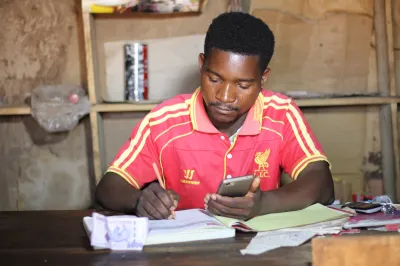

If, as the Findex says, the goal of financial inclusion is, “for account owners to benefit from the use of accounts for digital payments, savings and appropriate credit because such uses provide a range of positive benefits, which extend far beyond convenience” things do seem to be edging in the right direction, but broad usage beyond payments from these accounts isn’t happening – yet.

Green shoots

A whopping one in five Findex respondents reported personally receiving a government transfer in the past year – a five percentage point jump from 2017 and one no doubt greatly impacted by COVID-19 emergency relief payments. While significant, that worldwide average obscures some interesting regional differences in recipient percentages ranging from 30% of North Americans at the high end to 8% of Sub-Saharan Africans and 12% of South Asians. Significantly for financial inclusion, over the last Findex reporting period 67% of transfers in developing countries were made into an account of some kind.

It is worth underlining that most of these individuals are now in an ongoing financial relationship with their government as many payments (one-off COVID-19 relief payments notwithstanding) are recurring, with money hitting accounts monthly, quarterly or biannually. This regular infusion of liquidity is significant as it encourages engagement and leads to more familiarity with financial services and provides possibilities for further financial deepening.

Unfortunately, the Findex doesn’t allow us to disentangle government transfers from pension payments. It does, however, report that many adults receiving a government transfer or pension payment into an account also made payments, but a smaller share stored, saved or borrowed money.

In developing economies, 13% of adults received a government transfer or pension payment into an account over the past year. Of these payment recipients, 70% also made a digital payment from their account, including;

- 50% who made a digital merchant payment;

- 40% who made a bill payment using a mobile phone or the internet;

- 32% who made a utility payment from an account; and

- 22% who sent a domestic remittance payment from an account.

About half of those who received a government transfer or pension payment into their account over the same period also used their account to store money. About one-third of government transfer or pension recipients saved money formally, and one-third borrowed money formally.

This is all very encouraging and shows that government payments can set recipients down the path to more robust financial lives and, in time, the prospect of deeper financial inclusion. As we’ve stated above, this optimism must be tempered by the fact that Findex 2021 numbers may overstate G2P recipients’ breadth of usage of financial services vis a vis those receiving a government pension.

Untapped potential

Poor financial products, lacking financial education and the persistence of physical cash transfers mean that much of the potential of developing account ownership into financial inclusion remains unrealized. The 2021 Findex suggests a number of areas to focus on in future:

- Government transfer recipients (who disproportionately tend to be poor and financially inexperienced) may not be able to benefit from account ownership if they do not understand how to use financial services in a way that optimizes benefits and avoids consumer protection risks such as fraud, over-indebtedness and hidden fees. Tellingly, about two-thirds of unbanked adults said that if they opened an account (excluding mobile money) at a financial institution, they could not use it without help.

- 12% of those receiving government transfers still receive them in physical cash. Shifting these payments to financial institutions or mobile money accounts could create an entry point for financial inclusion.

- A common complaint among those receiving government transfers is that the payment products represent a poor user experience, are often difficult to use and recipients often contend with long lines at bank agents and struggle to get help when they have a question or a problem with their payments.

Finally, government transfers matter not only because they drive financial inclusion, but transfer volumes seem sure to balloon over the coming years. Two new drivers could well be climate change and inequality. First, climate. Those traditionally targeted by government transfers, such as the poor and vulnerable, also tend to be those most susceptible to climatic risks. As these populations grapple with adaptation or relocation, transfers will likely increasingly flow to them. Inequality, too, may drive transfer volumes as once fanciful ideas such as Universal Basic Income (UBI) enter the mainstream as a means of lifting those sections of society left behind. Let's see if they emerge and whether the Findex 2024 proves me right.

Add new comment