Freemium: Spawning An Insurance Market In Ghana

In the post last week we described how Tigo Family Care Insurance is leveraging the mobile channel to rewrite the insurance landscape in Ghana and expanding the borders of financial inclusion. This week, we go deeper into the business case to explore how the freemium strategy has contributed and what is being learned about mobile insurance for poor customers.

Three men stand together using mobile devices

Three men stand together using mobile devices

As a brief recap, Tigo Family Care Insurance is offered as a free product for Tigo voice customers who meet a threshold of airtime use in a given month; but it also allows customers to double their coverage for a fee of US$ 0.68 per month. The point of this pricing model is to introduce customers to a new product free of charge in the hope that they will see its merits and agree to start paying premiums. The free product generates no direct revenue, but is expected to bring indirect revenues by reducing churn and increasing airtime expenditure.

The question is: will that be enough? Can companies create healthy business lines serving poor people by offering products for free?

The answer seems to be yes, judging by initial lessons from Tigo Family Care Insurance in Ghana.

Premium uptake has been substantial: of a total 489,000 insurance subscribers, more than 55% are now signed up on the paying plan and the share is increasing. That means Tigo in a single year has gone from zero to 270,000 paying customers in a segment where only 7% previously had insurance. Tigo is convinced that the freemium model has been the main driver behind this achievement: the free offering created a market where none existed.

Churn is indeed lower on insurance subscribers than voice customers at large, though in Ghana the difference is so far not as great as anticipated. Average revenue per user (ARPU) is also higher for insurance customers, but the extra revenue is modest and less important than the churn factor. The business case thus still largely relies on direct revenues from premium payments to offset costs for the insurance premium, platform development, administration, claims and the dedicated sales force. Churn reduction and ARPU increases alone have not shown themselves to be sufficient to generate a higher profit margin on their own. However the churn and ARPU effects appear to vary significantly across countries and their contribution to revenue in other cases seems to be higher—we hope to come back to this subject in future posts.

As with any new and somewhat complex product, the skill and approach of the recruiting agents is paramount– agents may determine the fate of the business in their ability to communicate the product and its benefits to prospective customers. Once signed on, these customers have uneven cash flow and are highly price sensitive, so Tigo charges premium clients in daily installments of GHȼ 0.05 ($ 0.025) per day, deducted continually over the course of the month until the full GHȼ 1.3 fee has been collected. Even slightly higher increments significantly increased the number of customer complaints.

Traditional insurance underwriters may take some persuading before being willing to commit to such an untested product, delivery channel and market segment. If so, working with an intermediary institution like MicroEnsure or BIMA can ease their hesitation by reducing the costs of designing and administering the product, pre-processing claims, doing monitoring and reporting, etc.

So there you have it.

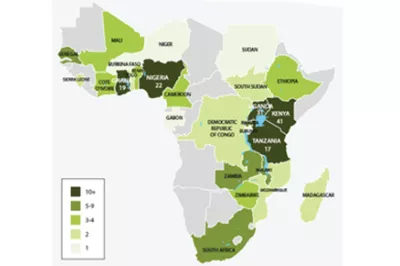

The initial experience with Tigo Family Care Insurance supports the idea that giving people value for free may be a good strategy to introduce a complex product in an underdeveloped market—call it the onboarding case for freemium. Tigo sure seems to think so and is planning to employ it in other countries, starting with Senegal where the Kiiray insurance product is currently being rolled out along the script developed in Ghana as well as Mauritius where they just launched. In more developed markets, however, customers may not need to be educated through a free product and competition may limit uptake volumes enough to weaken the case for a Freemium numbers play.

CGAP’s initial thinking around Freemium pricing was focused on mobile money, not microinsurance, and there are some signs that these ideas are starting to be tested in this space as well. In Kenya, where the breakthrough of mobile money into the mass market has unleashed a tidal wave of innovation, the recent entrant yuCash has made all transfers free in an attempt to gain market share from the dominant M-PESA. In Tanzania, Vodacom grants a modest level of coverage under its insurance product Faraja (which is normally premium-based) free of charge for customers making more than 10 mobile money transactions in a month. In Pakistan, Easypaisa’s Khushaal offering uses a freemium model for savings with embedded insurance for mobile account customers. We will be watching this space closely to report on developments and hopefully write a success story on Freemium strategies for mobile money before long.

------- The author is CGAP's consultant based in Accra, Ghana.

Add new comment