How Can Data Sharing Support Inclusion?

Diogo*, a street food vendor in Sao Paulo, counts himself lucky. Although COVID-19 led to several lockdowns in Sao Paulo and dried up demand for his street food, through a loan from Rebel (a fintech) he was able to keep his business afloat despite having been previously denied credit due to his lack of credit history and formal employment. By sharing his banking transaction data, including instant payment Pix transactions by his customers, Rebel was able to calculate an alternative credit score for Diogo and offer him a loan. This type of data sharing can now be facilitated by Brazil’s open finance regime.

In a recent blog, we highlighted that the poor are generating significant volumes of digital data due to increased digitization, and that these .

Data can be a driver of growth and change, especially for poor individuals in emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs). But for such digital data to create these opportunities, the data needs to flow freely – subject, of course, to individual consent. Further, the providers and other entities implicated in the data life cycle must be able to access this data in order to leverage it for their expertise and create use cases that can provide opportunities and support the resilience of low-income people in emerging markets. Such use cases include savings trackers, utility switching, personal finance and budgeting applications, automatic saving sweepers, debt rehabilitation services and credit products, which remain the most common data use case.

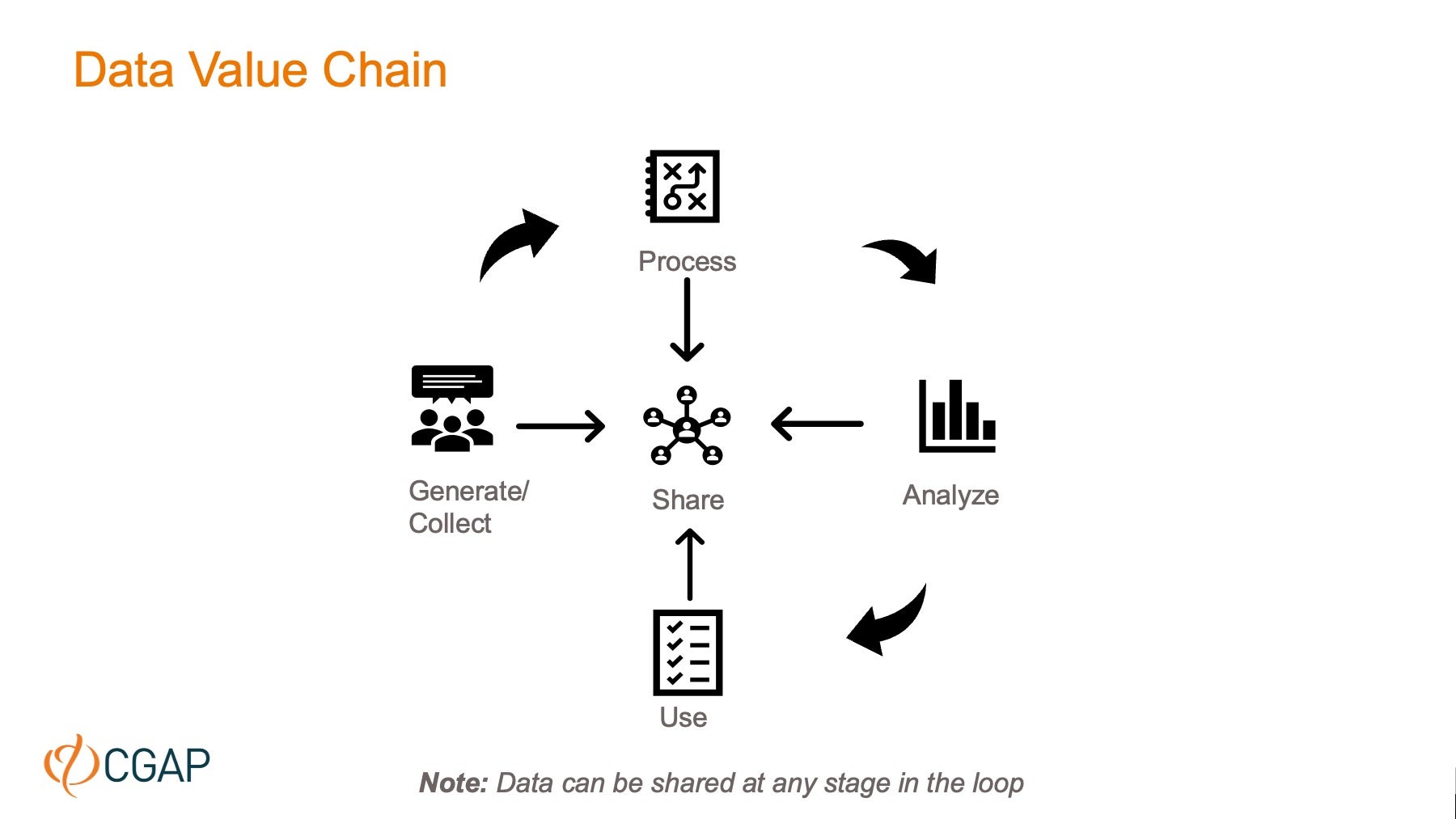

To understand how data can unlock these opportunities, a look at the data lifecycle is instructive.

Multiple pathways for data sharing

Data generated by individuals, including consumers, is collected by a data user who typically processes and analyzes the data before using it for their purposes. This collection is often based on explicit consent from the individual. If the data is unstructured when collected, it must first be structured before being processed. Data can be shared at any stage of the data life cycle, whether immediately after it is collected in raw form, right after it has been processed, or following any data analytics applied to it. Data is usually stored until it is no longer used and then generally deleted.

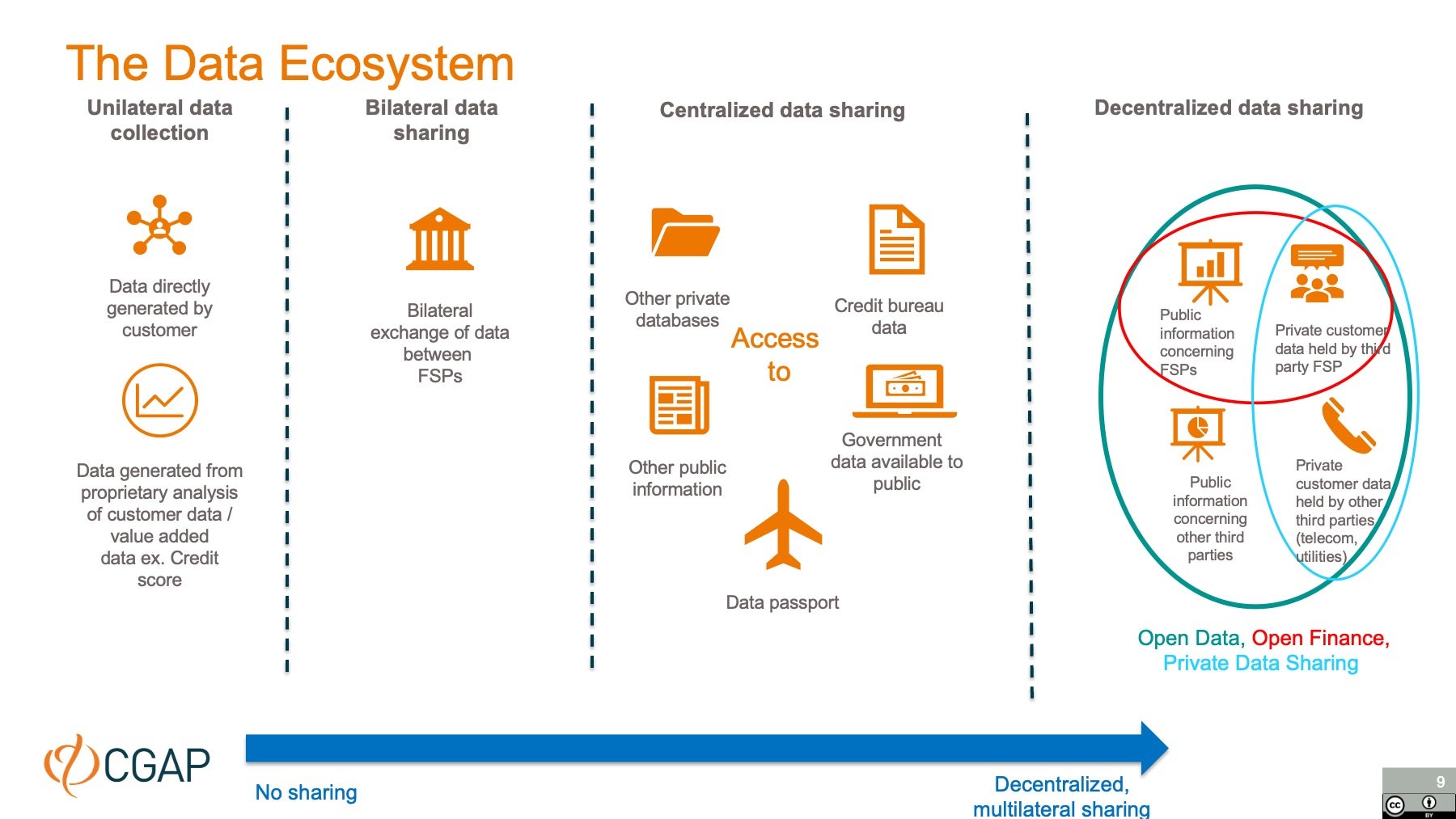

Although in theory, each data user can collect its own data directly from consumers, such unilateral data collection usually requires a contractual relationship and may be limited by data protection regulation. Thus, data is often locked in silos of databases held by users who have contractual or legal relationships with customers – such as banks, government agencies and telecom or social media companies. These data silos are often seen as contributing to the opaqueness and lack of competition in many industries, including financial services. , from finance to health care and utilities.

Third parties can enter into bilateral data-sharing agreements with data holders in order to access their data. An example of this is India-based fintech Fundfina, who partners with multiple companies to access their customers’ sales data. Using this alternative data they are able to provide loans to support the small businesses, for example, to finance their inventory. Raghvendra is an Eko agent in Bangalore and earns commissions from his work as such. Through a partnership with Eko and with the customer’s consent, Fundfina accesses Raghvendra’s sales data and pre-qualifies him for loans that are automatically repaid in small installments from his future income. These loans have allowed him to purchase inventory and expand his business to also sell school supplies and offer photocopy services.

Third parties can equally access databases, which may be public or private, often on a fee basis. One pertinent example in financial services is credit bureaus that provide potential lenders with both raw data and credit reports concerning consumers that wish to obtain a loan. In Brazil, credit bureaus are adding utility payments data to complement credit data and expand coverage of people without a credit history. Another example is data aggregator Plaid, which provides consumers in the U.S. with the ability to aggregate data from certain financial accounts in one place and then share that data to third parties to access certain financial services.

These are types of centralized data sharing, where the data to be shared is collected from various sources and centralized in the possession of one entity, i.e., a database owner, a data aggregator or even the consumer him or herself, if they are able to hold their data in a data passport. OneZeroMe and Dataswift have offered consumers in Brazil the ability to upload their social media data to a data passport that belongs to them, and from which they can share an alternative credit score to third parties upon request.

Lastly, we have decentralized data sharing, of which open finance regimes are a perfect example. Here, data is accessed from a variety of sources and directly shared with third parties based on the consent of the consumer, either through bilateral exchange via APIs between the data holder and user (the UK/EU model) or via a third-party intermediary (i.e., account aggregators in India).

Although there are many ways that data can be accessed by third parties, each model has its drawbacks. Bilateral sharing requires a contractual agreement and may be out of reach for some third parties. Most databases have a price tag (i.e., access on a cost basis) but the actual value for a potential buyer can be hard to estimate ex-ante, while data passports have not yet reached sufficient scale to be viably used by consumers on an exclusive basis. Open finance regimes often do away with contractual relationships and usually moderate the fee structure, but there needs to be political will to implement such frameworks and/or sufficient industry participation and alignment (depending on the implementation model).

What’s next? Diving deeper on data sharing models

. In our working paper on open banking, we argue that if open banking/open finance regimes are structured in a certain way, the framework can support the development of financial services use cases that serve low-income populations in EMDEs and thus bolster an inclusive data ecosystem. But such regimes are clearly not the only way inclusive data ecosystems can be supported. On this basis, CGAP’s Data Project looks to understand the various models of data sharing as set up above, and how these models may result in an inclusive data ecosystem.

As part of the Data Project, we are studying the digital data low-income individuals create to better understand the demand side of data ecosystems. We’re identifying and analyzing the key basic enablers of such an ecosystem, looking at data protection aspects of data sharing (one of the basic enablers we have so far identified), and undertaking pilots and case studies with financial service providers to understand how they can use these data trails to create inclusive products and services. , and are working to understand how these opportunities can be best leveraged in EMDEs. Data may not be the new oil (as claimed by the Economist), but it can help individuals like Diogo and Raghvendra weather crises and find new chances to grow their businesses.

*Diogo is a fictitious persona.

Add new comment