How Can the Poor Embark on a Pathway To Sustainable Livelihoods?

Creating the appropriate pathways for people to escape extreme poverty is one of the biggest challenges of our time.

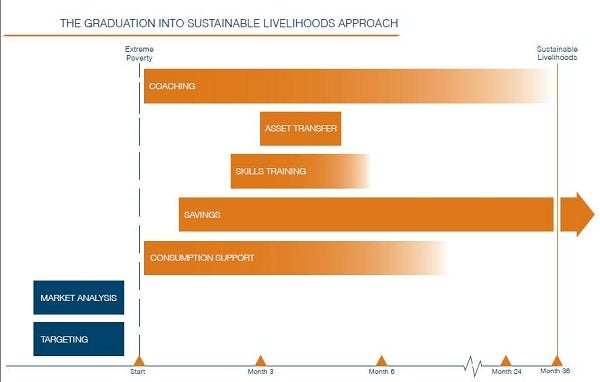

At CGAP, we’ve been exploring the potential of the Graduation into Sustainable Livelihoods Approach (Graduation Approach)—a model designed by BRAC in Bangladesh, which combines a mix of interventions to escape extreme poverty, ranging from safety nets and the creation of livelihoods, to access to financial services. Participants receive consumption support, access to savings services, skills training, a variety of assets, and regular individualized coaching over a period of 18-36 months. The goal is to help them create livelihoods that will end a lifelong existence in abject poverty.

At the global level, the extreme poor are those living with less than $1.25 a day, estimated in 2012 to be nearly 1.2 billion people. Individual countries may use higher poverty lines, but however defined, the extreme poor tend to be food insecure, lack education, usually have few or no assets, and are limited in their options to make a living. They often exist on the outskirts of society and lack self-confidence or opportunities to build the skills and resilience necessary to plan ahead.

In Paris next week about 100 leading policymakers, practitioners, and development experts will be gathering for the Reaching the Poorest Global Learning Event 2014 to look at what we’ve learned so far from implementation and research on the Graduation Program, which was launched by CGAP and the Ford Foundation in 2006. We’re also examining how we can incorporate this approach into social protection policies in order to reach the extreme poor at a large scale.

According to the International Labor Organization, only 20 percent of the world’s population has adequate social security coverage such as a pension or health insurance and more than half lack any coverage at all. In the least-developed countries fewer than 10 percent are covered by social security. This reflects the structure of the underlying economies and their large share of informal and/or self-employment. Fiscal constraints mean that many middle and low income countries will likely not be able to deliver universal rights-based social protection in the short- to medium-term. Safety nets, i.e., non-contributory transfer payments to those in need have generally also been poorly developed: in Africa close to three-quarters of the 20% poorest families receive no transfers at all (World Bank ASPIRE Database, 2014). Given these realities, we feel it’s important to try new approaches to meet the ambitious goal of ending extreme poverty by 2030.

We realize there are many challenges to working with the poorest, which are often harder to reach and feel pressured to prioritize immediate needs over longer-term investments. Moreover, interventions are more expensive and complex because of the need to overcome the multiple barriers of extreme poverty. However, the poorest are also likely to benefit most from any interventions. When given the opportunity, they tend to increase their household’s food consumption first, which holds great promise for future generations since child malnutrition has many long-term negative consequences, including lower IQ and stunting. Both of these drag down a country’s growth potential.

In our mind, the Graduation Approach is one pragmatic pathway to address extreme poverty. We’ve been testing this approach since 2006 with 10 pilots in eight countries. By 2012, between 75 and 98 percent of participants at six of the 10 CGAP-Ford Foundation Graduation Pilots met locally-determined criteria for graduation into sustainable livelihoods, including indicators of improved nutrition, increased assets, and enhanced social capital. Early results from randomized control trial impact assessments show very promising results: beneficiaries served by BRAC (Bangladesh), Bandhan (India), REST (Ethiopia), and four sites in Pakistan increased total annual household consumption by 11-36% compared to control groups. Assets, including savings and livestock, increased as well. Another pilot in Honduras increased happiness and food security, despite having no impact on other measures of consumption.

Behind the figures are the firsthand results of the Graduation Program. For example in Ethiopia, Asqual Gimay, 31, a single mother living with her seven year-old-daughter, her ailing mother, and a divorced sister had no land, limited access to food and very little cash income when she joined the CGAP-Ford Foundation Ethiopia Graduation Pilot: “I’m usually not lucky, so I’m happy I got a chance to be in this program,” she told researchers in 2010. As part of the program, Asqual chose to start a bee-keeping business, with a clear goal in sight: “I want to be rich because I have suffered for a long time because of my poverty.” Her business expanded rapidly during the program: in 2012 she had 10 bee colonies and still occasionally worked as a daily wage labourer to earn extra cash. She also managed to save 12,000 Ethiopian Birr (approximately $USD 645) at a local microfinance institution: “Now I feel confident that I can provide for my daughter in all ways – material and otherwise. I can even cover the cost of [her] long term study. I can buy her enough clothes. Now I want a separate house and stop crop-sharing. I want to buy oxen and hire paid laborers instead.”

Asqual Gimay, CGAP-Ford Foundation Ethiopia Graduation pilot participant

Asqual Gimay, CGAP-Ford Foundation Ethiopia Graduation pilot participant

Asqual Gimay, CGAP-Ford Foundation Ethiopia Graduation Pilot participant. Photo credit: BRAC Development Institute*

We know that not everyone will be as successful as Asqual: the Graduation Approach is not a silver bullet to ending extreme poverty. But it holds great potential for a large proportion of the poorest. At our Learning Event next week, academics will be sharing some new data on the relative efficiency of the Graduation Approach versus other interventions. We will also try to find innovative ideas to address the many design constraints (e.g. how to provide adequate coaching for large numbers of people?) and coordination challenges that governments face in reaching the poorest at scale with multi-sector interventions. We’ll keep you posted on the outcomes via this blog, the Graduation Program’s Community of Practice website, and share new ideas on Twitter, using our meeting hashtag #reachingthepoorest.

*Asqual Gimay’s story is summarized from Pathways out of the Productive Safety Net Programme: Lessons from Graduation Pilot in Ethiopia, BRAC Development Institute (BDI), 2012. Since 2010, BDI has been conducting qualitative research at the Ethiopia Graduation Pilot, following the lives of 22 participants.

Add new comment