How Greenfield MFIs Advance Market Development in Africa

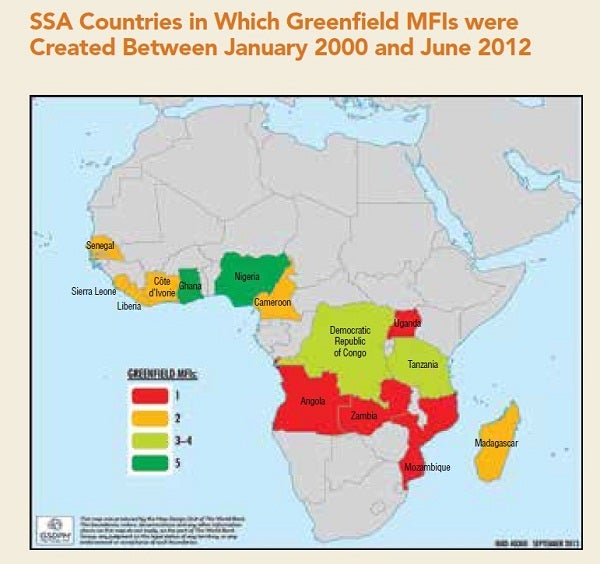

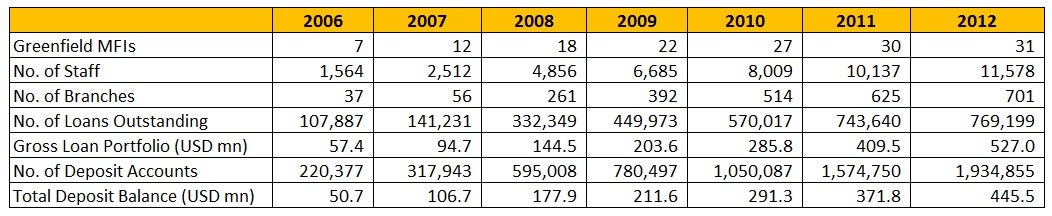

The proliferation of greenfield microfinance institutions (MFIs) - newly created financial institutions established without pre-existing infrastructure, staff, clients or portfolios – has been a trend across Africa in the last decade. By 2012, 31 greenfield MFIs had started operations in twelve countries (see map). CGAP and IFC studied their performance and analyzed the business models of the organizing bodies that created them, including holding companies. One of our objectives was to test the theory that retail institutions can positively impact responsible market development by successfully demonstrating the viability of institutions that serve base of the pyramid customer segments, especially in frontier markets.

The holding companies that have created greenfield MFIs in Africa, such as ProCredit, Opportunity, ASA and Ecobank, have found ways to overcome and address some of the key challenges operating in difficult markets. They have done so by adopting a systematized approach that relies on strict procedures and standards, heavy investment in professional development and sufficient patience and resources. For the creation of market leaders in microfinance, the holding companies attracted public funding, most notably from development finance institutions (DFIs). The greenfield MFIs studied needed on average $6-$8 million for initial capital and external support for technical assistance for the first 3-4 years of operations.

Source: Greenfield MFIs in Sub-Saharan Africa

We studied the market development effects associated with the start-up of greenfield MFIs in three countries with different levels of financial sector development: the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Ghana and Madagascar. Each country has several greenfield MFIs, and has at least two that have been operational for more than five years, increasing the likelihood that effects of their interaction with the market can be observed. It’s complicated to attribute changes in a market to the intervention of one or more individual institutions. However, using a mix of quantitative and qualitative information, we examined the effects of greenfield MFIs on financial access and market development through the lens of staff recruitment and investment in training.

Do greenfield MFIs demonstrate the viability of serving low-income customers? The holding companies all use a tested approach and patient capital to move the new institutions through the difficult start-up phase onto a growth trajectory. Greenfield MFIs tend to break even in 3-5 years. Half of the 31 MFI studied had positive returns by the end of 2012. While many greenfield MFIs are still young, there are signs of solid long-term institution building and some positive spill-over effects for local markets. We found some evidence of the transfer of practices to other market participants, by example or through staff movement. For instance, in the DRC, the performance of ProCredit, which reached financial sustainability in three years, triggered banks such as BIC and TMB to downscale and serve the small and medium sized enterprise segment. To acquire the necessary expertise they partially relied on former employees from ProCredit to roll out these services.

How do staff recruitment and training investments of greenfield MFIs affect the rest of the market? The most significant effect of greenfield MFIs on market development appears to be their contribution to professional development in the banking and microfinance sectors. They employ and train an impressive number of young adults (typically with little previous work experience). In Ghana, the five greenfield MFIs employed more than 2,000 staff while the entire mainstream banking sector employed 16,000 in 2011. In Madagascar, Access Banque and MicroCred had more than 1,000 staff, which represented 23% of staff in the microfinance sector and close to 19% of banking sector employees. Greenfield MFIs typically have an intensive and systematic approach to staff selection, recruitment and training and spend 3 to 5% of their operating budget on staff development. Much of the technical assistance funding is used for these training efforts. The employees of greenfield MFIs eventually become attractive candidates for mainstream banks. Some holding companies calculate that they will train two to three times the number of required staff to address expected attrition to local financial institutions.

The report highlights other effects on market development through the introduction of new products, the replication of credit policies and service standards by other financial institutions and ways in which greenfield MFIs have contributed to a more favorable regulatory environment. However, demonstration effects do not happen automatically and the transfer of know-how and experience of the greenfield business model has not happened systematically. Double bottom line investors, in particular the DFIs, should continue to promote the sharing of information on lessons learned and performance of greenfield MFIs to ensure purposeful demonstration.

For a summary version of this report, please see IFC's Field Note. You can read the full paper on CGAP.org.

Comments

Je vous remercie pour cette

Je vous remercie pour cette communication et je pourrais m'inspirer et vous donner des exemples locaux de Guinée Conakry dans le furtur proche !

Add new comment