Minimize Risk to Drive Smallholder Adoption of DFS

For the world’s smallholder families, risk is an ever-present part of daily life. Faced with a changing climate and economic transformation, smallholders are constantly living under the shadow of threats to their already tenuous livelihoods. Considering this uncertainty, and equipped with few safety nets and limited savings to cushion against a major loss, it comes as no surprise that smallholders are typically reluctant to risk what little they have by trying a new and unfamiliar digital financial product or service.

Minimizing the risk of trying digital financial services was one of the key takeaways from CGAP’s four smallholder-focused human-centered design projects, lessons from which are detailed in a recently released publication, "Designing Digital Financial Services for Smallholder Families." Working with smallholders, designers identified three main product features that are critical to minimizing the perceived risk to smallholder families when trying DFS for the first time: flexibility, familiarity, and tangibility.

Flexibility

Facing myriad risks and volatile livelihoods, smallholders are hesitant to try digital services that make it difficult to access their money in a time of need.

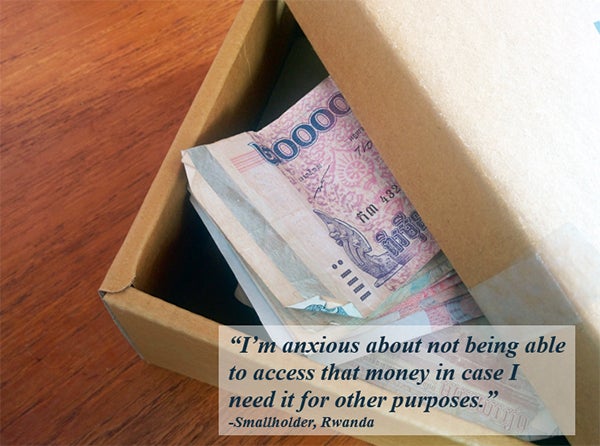

One of the most important factors when seeking to minimize the perceived risk of a new digital financial product or service is flexibility. For example, when considering whether or not to try a new goal-based savings account, a customer’s decision may hinge on whether or not she can easily withdraw that money on demand. “I’m anxious about not being able to access that money in case I need it for other purposes,” explained a Rwandan cooperative group member when asked about savings accounts.

CGAP’s previous HCD work, which did not focus on smallholders, found that low-income customers prefer terms and conditions that encourage discipline, such as penalties for early withdrawal. However, even though many smallholders expressed a similar desire for features that promote discipline, they told designers that they would be less likely to try a digital savings account that penalized them for accessing their money in a time of emergency.

When designing a digital goal-based savings product in Cambodia, smallholders emphasized the importance of having flexible access to their funds, even as they sought features that would encourage savings discipline. After considering several strategies, designers settled on an incentive-based system that would offer preferential interest rates on deposits to customers who stuck to their savings plans. Still, to ensure that smallholders had some “skin in the game” designers also recommended a modest minimum balance requirement of US$3.

This prioritization of flexibility among smallholders does not always hold true. While flexible withdrawals were important to smallholders in Cambodia and Rwanda, Zimbabwean smallholders felt that discipline was a priority that trumped flexibility. The majority of Zimbabwean smallholders who participated in the prototyping of a goal-based savings product for school fees actually preferred that their savings remained “locked,” which was a reflection of the importance that they place on their children’s education. It also pointed to a larger issue of gender in management of household finances: some female smallholders insisted that locking savings would prevent their husbands from using school fee money for other purposes.

Aside from providing access to savings in times of need, several additional strategies exist that can increase the perceived flexibility of DFS. myAgro, which offers a mobile layaway service for purchasing packages of seeds and fertilizer in Senegal, found that many customers were hesitant to pay in advance without being sure of the quality of the inputs and their impact on crop yields. Instead of using the service to purchase all of their seed and fertilizer, they preferred to purchase small packages that they could test on just a portion of their fields. These behavioral observations led to the design of micro-packages for things like vegetable seeds (among other input combinations) that smallholders could use to quickly test the myAgro system. Because vegetables can be grown year round in small gardens, these low-cost packages allowed farmers to get results in a matter of weeks instead of months, thereby allaying fears that myAgro would run off with their money and giving them the confidence to enroll for larger input packages.

Familiarity

New technology can be intimidating, especially for smallholders who may be interacting with digital services for the first time. Designers in Rwanda turned to the country’s ubiquitous savings groups as entry points for DFS, with the goal of increasing the familiarity of these services.

Another important approach to minimizing perceived risk is to design products that feel familiar to smallholder families. As CGAP has found in previous design projects, poor people can often be uncomfortable with, or even fearful of new technology. This is especially true of smallholder families, who tend to have even less exposure to new technologies than their poor urban or nonagricultural peers. This discomfort and lack of familiarity with technology can increase perceptions of risk when considering whether or not to try a new digital financial service.

To overcome this aversion to technology, designers sought to leverage existing financial behaviors in their product concepts. For instance, designers in Rwanda used savings groups as a channel through which to introduce smallholders to formal financial services. The first step in this process was to simply digitize savings group transactions, which not only provided groups with more efficient and secure management tools, but also began to familiarize them with UOB’s mobile banking platform.

myAgro’s approach to customer deposits offers another example of how FSPs can make DFS feel more familiar to smallholder families. By using scratch cards to add credit to customers’ layaway accounts, which mimics the already well-established behavior of purchasing airtime top-up scratch cards, myAgro offers smallholders a familiar touch point in their digital interaction with the layaway platform.

Tangibility

A myAgro customer in Senegal displays the scratch cards that he holds onto to keep track of his layaway balance. Making digital finance more tangible is key to driving service adoption among smallholders, who may be more comfortable saving and transacting in-kind.

The third consideration when seeking to minimize risk perceptions is tangibility. Throughout interactions with smallholder families, designers often observed a tendency to save in-kind rather than in cash (or in a bank account). From jewelry to livestock, many smallholders prefer these stores of value due to their tangibility, even though they are sometimes forced to sell them at a loss when they need cash: “We bought jewelry for our children… When we need money, we sell the jewelry back to the goldsmith,” explained one smallholder in Cambodia.

Given this preference for tangibility, transitioning smallholder families from a practice of saving in-kind to saving in electronic stores of value will require a “double jump” from in-kind, to cash, to digital. Considering the already low use of cash as a store of value among smallholders, there is a clear need to make DFS seem more tangible if FSPs want to spur greater adoption of these services.

The myAgro scratch card model also provides an interesting insight into how FSPs can minimize risk perceptions by increasing the tangibility of DFS. Although myAgro did not necessarily consider tangibility when designing the scratch card system (see familiarity example above), the designers observed that customers were actually holding onto the scratch cards even after the secret code had already been submitted. For these smallholders, the cards represented tangible proof of the electronic value in their layaway accounts even though such proof was also available digitally on their phones.

Over the following months and years, CGAP will continue to collaborate with designers and our FSP partners to see some of these product concepts through to implementation. As the products are rolled out to smallholders in Zimbabwe, Senegal, Rwanda, and Cambodia, some of the design principles will be validated along the way, while others will need to be reevaluated in light of new information. In the meantime, FSPs should constantly be testing their assumptions in the field with customers, and iterating based on the feedback that they receive. While the recommendations outlined here can serve as a starting point, they are by no means a substitute for designing along with your customer.

Add new comment