A New Generation of Government-to-Person Payments Is Emerging

A new generation of government-to-person (G2P) payment systems is emerging in Africa, Asia and the Pacific. As described in CGAP’s new publication, “The Future of G2P Payments: Expanding Customer Choice,” modern approaches of transferring cash assistance can reduce costs for governments, significantly improve recipients’ access to payments and bring digital G2P one step closer to becoming the large-scale conduit for financial inclusion that observers have always hoped it would be.

The main difference between these new systems and traditional approaches to digital G2P is that they give people greater choice over how to receive government payments. Instead of the government selecting a financial services provider (FSP) and opening accounts for recipients, these systems allow people to choose where they open accounts and access their payments. This is possible thanks to the increasingly advanced and integrated payments infrastructure in low- and lower-middle-income countries, which enables G2P programs to channel payments through multiple providers. Modern G2P systems run on a shared, connected payments infrastructure that multiple programs and multiple providers can plug into.

Shared, Inclusive Payments Infrastructure Underlying New G2P Systems

The result of giving recipients greater choice is that FSPs start to see recipients — not governments — as the customers they seek to serve, and they have a stronger incentive to improve the customer experience. This is an important shift with implications for FSPs, recipients and, ultimately, financial inclusion.

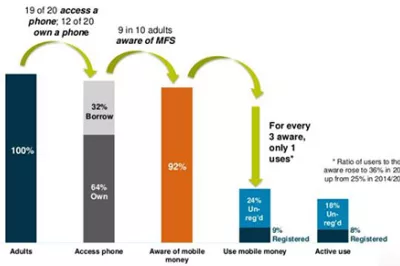

When governments and donors started to digitize social transfer programs in the early 2000s, many in the financial inclusion community saw an opportunity to improve vulnerable populations’ access to and use of formal financial services. However, the evidence for meaningful financial inclusion through digital G2P payments remains thin. Studies show that most recipients withdraw their payments as soon as they arrive instead of using their accounts to save or transact digitally. And while digitization has created efficiencies for governments, the inconveniences and costs associated with accessing payments at government-prescribed cash-out points means that recipients perceive little improvement over in-kind or cash transfers. Bad customer experiences do little to encourage people to use DFS more broadly, a constraint on G2P payments’ potential to advance financial inclusion at a large scale.

The new “direct-to-citizen” payments system in Bangladesh shows what the future of G2P payments could look like. In 2016, Bangladesh’s Access-to-Innovation (a2i) Initiative launched an effort to improve how G2P payments are transferred to citizens. One of its largest G2P programs is the Old Age Allowance, which provides a regular allowance to over 3.5 million elderly people. The program suffered from the typical problems associated with digital G2P systems that lack choice. Payments were unpredictable in terms of frequency and amount, there were high levels of fraud and related financial losses and the collection of payments was inconvenient and costly. An assessment of their experiences revealed that recipients spent on average three hours traveling to collection points and waiting in lines to collect their payments. Especially for the elderly, the need to travel far from home and then stand in line without any sitting arrangements represented commonly cited pain points. In addition to the physical strains, the journey cost them on average 23 percent of their allowance, and several recipients complained about account opening fees and additional costs for borrowing money when disbursements were delayed. The customer experience was hardly any better in the other 100+ G2P programs.

Typical Pain Points for People Receiving Old Age Allowance in Bangladesh

To address these challenges, a2i designed a more integrated, citizen-centric G2P payments architecture that allows any government program to channel payments through a shared payments infrastructure to accounts at multiple providers. This new design enables citizens to choose their preferred FSP and access point. It also enables citizens to switch providers if their circumstances change or they discover a better service.

Giving choice to recipients will incentivize providers to compete for them as customers. For providers to capture a part of the country’s $150 million annual G2P transfer volumes, they now have to win and maintain customers’ trust and interest. Bangladesh’s direct-to-citizen payments system was piloted with 128,000 recipients across three G2P programs in mid-2018. The pilots proof-tested the technical viability of customer choice, the involvement of multiple government programs, the functionality of a newly developed ID-account mapper (i.e., a directory that links individuals’ ID numbers with their payment addresses) and the routing of payments directly from the treasury. In a next step, a2i and the ministries will need to invest in educating recipients on how to choose an appropriate financial institution to make customer choice a reality.

Based on these recent developments in Bangladesh and similar efforts in Zambia, Tanzania and Kenya, CGAP is seeing what the future of G2P payments may look like and the benefits they can bring to customers, governments and the financial system. Most importantly, we see an opportunity for G2P recipients to receive better payment services from providers they trust and value — an important first step for a sustained financial inclusion journey.

A supplementary case study can be found here.

Add new comment