Papayas and Digital Finance: Emerging Consumer Risks in Colombia

Every month, Angelica, who lives on the outskirts of Bogota, Colombia, receives the Familias en Accion government cash transfer benefit via the Daviplata platform. She isn’t too comfortable with technology, so her sister makes the withdrawals for her. In fact, Angelica registered her account under her sister’s SIM card, since she didn’t have a phone back then. Her PIN and account were blocked a few months ago, and she didn’t know what to do. She was very upset since she relies on the monthly amount to pay for her young son’s basic needs. She tried going to Daviplata agents to retrieve her blocked money instead, but they curtly told her “You are not on the list [to receive payments],” and sent her away. She then remembered there was an SMS string she could dial to get help, but she has to wait for a call-back, which can take up to 8 days, with no assurance that in the end she would receive help.

We met Angelica in August 2014 when Bankable Frontier Associates carried out one of four country “deep dives” on emerging consumer risks in digital finance for CGAP. We found that digital finance and branchless banking clients are cautious. They told us repeatedly “No dar papaya” (“Don’t give a papaya”): don’t put yourself in a position where you can be taken advantage of… ” If something goes wrong, such as when a client’s PIN is stolen, clients tend to blame themselves for not being sufficiently alert. Many clients take precautions to protect their money; some never travel alone when they visit an agent or an ATM, or they cover transaction screens with their hand when entering a PIN. Colombians have not forgotten a time about six years ago when destructive financial pyramid schemes were common in the country, and their residual caution is still apparent.

But, as we found, these basic precautions do not protect clients from all potential risks. Some mobile banking interfaces make it difficult for clients to use standard protections to safeguard PINs and do their own transactions. And their lack of clarity about and confidence in recourse options make it less likely that they will complain or seek help when something does go wrong.

Here are some key takeaways from our research with mobile money consumers, providers and other stakeholders in Colombia.

Clients report network outages are the most frequent problem. Generally, we found that while clients appreciate the convenience and speed of digital financial services, network outages are a common complaint. Many clients said that they can get around network issues by going to another agent or transacting at a different time of day. However, interviews with agent network managers on the supply side revealed a more insidious aspect of network unreliability: it allows for increased potential of agent fraud.

When the network is down, clients leave money with agents to pay bills once the network is back online. Unfortunately, some of these agents hold onto the cash and use it for their own needs, paying the client’s bills at the last minute. In Colombia this is known as “jineteo”— keeping cash to use for one’s own purposes. Clients would not know that the agent used their money in this way unless the agent ran into a liquidity problem. Interestingly, although agent managers are aware of this practice, banks did not report it during our interviews. Indeed, the banks and other providers did not seem well-informed about the impact of network down time on the customer experience and mobile and agent financial transactions.

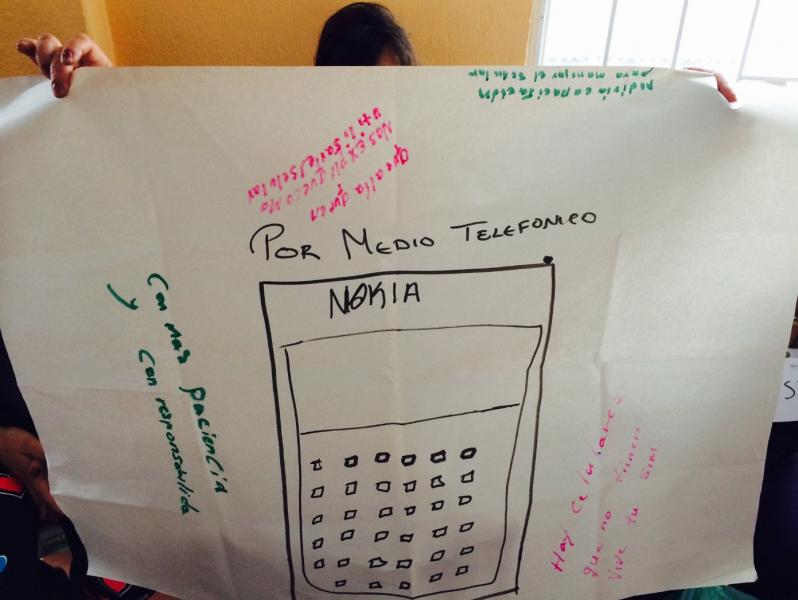

“What would an easier to use mobile money interface look like?” – Female focus group design workshop

Clients find digital financial services difficult to use – their coping strategies open them up to risks. Many clients, particularly older ones, told us they found mobile money interfaces and ATMs confusing and difficult to use. These clients often rely on members of their social network, especially family members, to carry out transactions for them. One woman we spoke with in Usme, in the very south of Bogota, told us: “My sister always withdraws and brings the money for me…. She tries to teach me, but I’m scared with all those buttons of messing up and losing the money.”

Clients who are uncomfortable with using new technology for financial transactions told us they share their PINs freely with others who help them access their accounts. While most participants fully trust their helpers, many clients also said that they know people who have been victims of fraud because they shared their PINs.

In an iterative informal focus group design workshop, clients helped us come up with innovative ideas for more user-friendly mobile interfaces. Clients told us that mobile money menus should be interface agnostic. The menus currently do not work on some phones, and the menu also changes depending on the phone, making it harder for clients to figure out how to work it and how to get help from peers. Many respondents wanted more training on how to use interfaces.

Clients are most concerned about the confusion around recourse: where to complain and whether it is worth the hassle. Clients expressed concern regarding the lack of information about the correct channels for resolving a problem, fueling a fear of having no recourse when they experience difficulties or are victims of fraud or unfair practices. Others were unsure which channels were the most effective for complaints. Clients said they would complain to another agent or to the police if they had a problem with an agent or mobile money, rather than complaining to the bank. Often, this approach is based on unsatisfactory experiences in trying to resolve complaints and problems. Clients also felt like they “lacked power” in resource exchanges. For example, one well-known customer hotline can be accessed only by using an SMS string and clients have to wait for a call-back, which can take up to eight days.

We asked participants to describe their ideal helpline. Clients said that when they had issues, they:

- Wanted to reach someone right away by phone, not SMS strings;

- Did not want to deal with prerecorded answer options or hold music;

- Preferred access to several different direct numbers in case one was busy;

- Wished the process was quicker;

- Suggested that their interactions with help staff be assigned a unique record number so that their efforts to solve a problem are properly documented and they can avoid continuously repeating details of their situation to additional help center staff.

- Requested that representatives be available for longer hours, be more respectful, and be more knowledgeable.

The Colombian market is nascent compared with others. While overall feedback from our client research was positive, it’s clear that real and potential risks do exist. Results from our brief design workshops with digital financial services clients point to simple, yet innovative ideas to help mitigate certain risks. At a time when Colombia has just issued regulations to open up the market and permit non-banks to offer additional services beyond cash out and bill payments, strengthening consumer trust and confidence is crucial to promote increased uptake and usage of DFS.

Read the country deep-dive, Emerging Risks to Consumer Protection: Key Findings in Colombia.

Add new comment