Poverty, Social Assistance and the "Graduation" Agenda

The big picture of poverty reduction trends and forecasts are encouraging but imply increasing complexity for poverty reduction strategies.

As we approach the end date to reach the Millennium Development Goals in 2015, there is a new spate of thinking on how to reduce global poverty and what can be achieved over the next 15 years. Noted Australian economist Martin Ravallion issued a report last year on the prospects for ending extreme poverty and the Brookings Institution published some interactive infographics on the topic. Another big picture analysis has been offered by Yoshida et al. Among their takeaways are:

- If current growth trends continue, we will still see strong progress on poverty reduction, but not its elimination;

- That the inclusiveness/income distribution of that growth will matter;

- That the geography of poverty shifts over the decades from 1990 to 2030, with China, then India then Sub-Saharan Africa leading the charge in poverty reduction;

- That the share of the poor in the world that live in fragile and conflict affected states will rise to half by 2015 and to two-thirds by 2030;

- That as the world, or a country, gets closer to reducing poverty, it will become incrementally harder to make progress;

- That shocks – macro instability, bad weather, civil unrest and the like – can quickly reduce years of progress on poverty reduction;

- Business as usual won’t get us to zero, or very low, poverty levels.

If we take a more country-focused view, we note that countries’ poverty lines rise with their income so even countries with little or no poverty as measured at the World Bank’s $1.25 per person per day may still be focused on their own poorer citizens, though as these become fewer they may also differ more from the non-poor. Thus different poverty reduction strategies may be needed. Moreover, as the income of countries increase, policy attention may be increasingly focused on those who have risen out of poverty but haven’t quite made it into the middle class, or to those in the middle class. In Latin America, for example, Ferreira et al show that there are now about as many middle class as poor people, and more of those in between.

Social Assistance is taking a bigger role in poverty reduction

In 1990, when the above cited poverty projections started, social assistance didn’t play a big role in poverty reduction strategies, but this is changing rapidly. The number of World Bank client countries with flagship social assistance transfer programs has increased dramatically, with dozens of new or reformed conditional cash transfers, social pensions or public works programs. Though numbers are hard to tally precisely, the increase in programs with modern administration and design has gone up several-fold. Social assistance is playing a bigger role within countries too. In the 10 countries for which we have comparable data in the Social Protection Database for Latin America compiled by the World Bank, spending on social assistance programs trebled over the decade from 2000 to 2010, from 0.4% of GDP to 1.2% of GDP. In Latin America, where increased labor earnings were the predominant factor in reduced inequality, transfer programs still account for a significant share of the reduction in inequality – about 20 percent, as calculated by Azevedo et al. There are many factors behind this sea change, but it is consistent with the need to bring in new strategies as poverty falls. It is also consistent with the increasing evidence that social protection is not only a viable tool for redistribution, but can contribute to inclusive growth (see for example Grosh et al. 2009, World Bank 2012,or Alderman and Yemtsov, 2013 Social Assistance Supports Inclusive Growth (also known as “redistribution”)

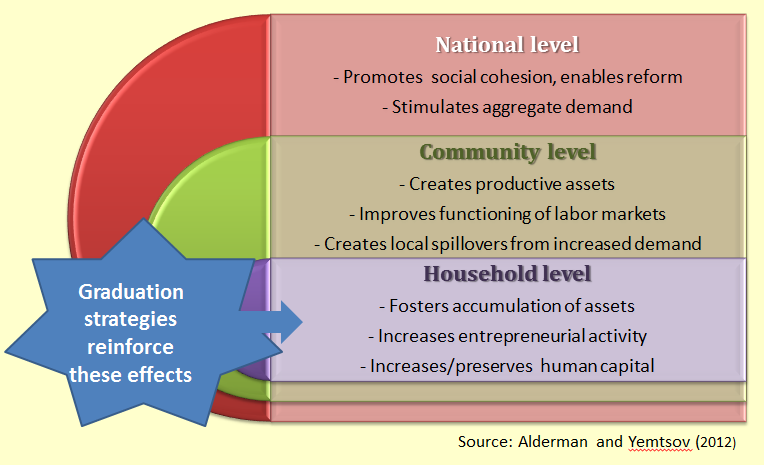

Graphic showing social assistance support of inclusive growth.

Graphic showing social assistance support of inclusive growth.

As Social Assistance has Grown, so too has Interest in the Graduation Agenda

Once a country has a sizable and sound social assistance program or two, with all the basic mechanics of eligibility and payments working, attention often turns to how to fine-tune its impact and thus to help people graduate out of extreme poverty and into sustainable livelihoods. To me, the graduation agenda is about raising the level or stability of the autonomous income of recipients of social assistance through linkages between the basic income support provided by social assistance and some other program elements – asset transfers, financial inclusion, training, job search assistance or the like. All of these interventions are included in the CGAP-Ford Foundation Graduation Program which is being discussed at a learning event in Paris this week. (I discount here the all-too-common sense of ‘graduation’ as a euphemism for removing people from the rolls of social assistance based on anything other than the improved welfare of those people).

The premise of the graduation through linking income support to other things is attractive and intuitive but it may not be easy. After all, the people in social assistance haven’t [yet] prospered with the set of opportunities and programs available to them in their present form. To make graduation work implies figuring out what is missing. Is it direct linkages? Is it the other services? Is it the quality of the other services? How do you match the social assistance recipients, who are diverse, with services, which are also diverse? How do you get different service providers to coordinate? How many people will have their income raised and how fast? How much has to be invested in either the linkages or the complementary services? What tradeoffs are implied? These are the issues that the Reaching the Poorest Global Learning Event 2014 is designed to reflect on. I look forward to the learning.

Comments

This is quite interesting,

This is quite interesting,

Add new comment