USSD Access: A Gateway and Barrier to Effective Competition

Approximately 90% of developing mobile phone users do not yet use smartphones, relying instead on basic phones with little or no web capability. This means that to serve the unbanked, mobile financial service providers continue to rely on USSD technology to bring innovations like mobile money to the unbanked.

A challenge with USSD is that MNOs have a monopoly over the service, leaving providers at their mercy when it comes to pricing and licensing, and creating a conflict of interest: In many markets, financial institutions are both customers of, and competitors to mobile network operators. This conflict of interest raises several concerns for promoting fair competition in mobile financial services that should be of interest not only to financial and telecommunications regulators, but also to competition authorities as well. Our research in Kenya and Tanzania identified several competition-relevant issues in USSD access, which are highlighted below.

Cost and cost variance in USSD

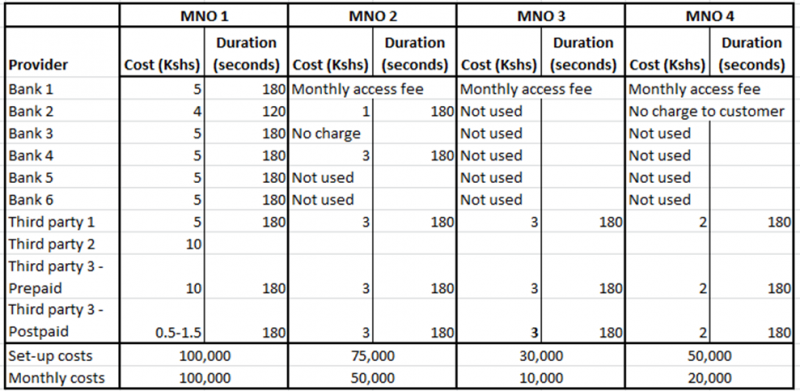

In Kenya, consultations with financial institutions and other providers revealed a wide range of prices paid by providers to MNOs for USSD sessions, from one to ten Kenyan Shillings per session (see table). In contrast, in Tanzania prices appeared to be more consistent, and one provider—Tigo—has even opened up its USSD to several financial institutions at no cost. This difference may be in part due to the monopoly-level market share in mobile money of Safaricom, which gives them considerable leverage over competing financial service providers seeking to use USSD to provide services to their consumers. By contrast in Tanzania market share is more dispersed between three MNOs, with leading provider Vodacom having 53% market share, Tigo 18%, Airtel 13%, and 16% users of multiple mobile money providers, and anecdotal conversations with providers in the market did not raise as many concerns about USSD access as our conversations in Kenya.

Table 1: Survey of costs of USSD access paid by MFS providers to MNOs in Kenya (July-August 2014)

Our research also showed the role market power may play in USSD price, as the prices paid by providers varied significantly across MNOs, with larger banks enjoying better terms than third-party providers. This means new or smaller entrants to a market may be at a disadvantage in channel access and pricing, which can hinder innovation and greater competition. This disadvantage may in some cases impact smaller financial service providers in similar ways to its impact on third party providers. One financial institution in Tanzania noted they prefer using third-party aggregators for USSD, as these aggregators have more leverage to negotiate better terms with the MNOs since they are negotiating on behalf of a number of firms and regarding a higher overall volume of services and transactions.

However, setting fair prices for USSD remains difficult due to the opacity of the true cost of a USSD session. Without greater detail on the costs incurred by MNOs to offer the USSD channel it is not possible to determine if USSD sessions are priced fairly or enjoy exorbitant markups. This suggests a clear role for regulators in the telecommunications and financial sectors, as well as competition authorities. A regulatory inquiry could gather information from all providers that would clarify the commercial terms between MNOs and providers for USSD channel access across sectors, firm size and product type; as well as the fixed and incremental costs to MNOs of delivering USSD, in order to determine whether there is exorbitant or discriminatory pricing in the market.

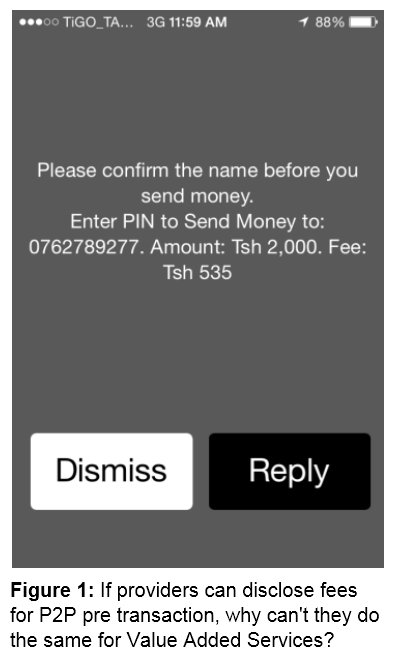

In addition to the costs charged to providers by MNOs, there are costs passed on to consumers for the transactions they make via USSD sessions. This raises a basic consumer protection concern that needs to be fixed in Kenya, Tanzania and many other markets. In sum, there is a near total lack of transparency of disclosure of USSD costs to consumers pre-purchase during USSD-based transactions in both Kenya and Tanzania. In almost all such cases the consumer also bears the USSD session costs in their entirety via a pass-through from the bank or other third party, which exacerbates the consumer protection issues of no pre-purchase price disclosure.

This means most consumers are not aware of the costs they pay for transactions such as bill pay, or transfers in mobile money, part of which is the cost of USSD channel access. This was confirmed in a CGAP experiment with 500 low-income consumers in Nairobi, where we found that for consumers who used Pay Bill services, 20% reported not knowing the fee on their last Pay Bill transaction, while 35% of them thought the fee was zero, and those who estimated costs generally estimated them at 2-3% of the transaction amount. This occurs despite requirements in the Communications Authority’s “Procedures and Guidelines for the Management of Telecommunications Short Codes and Premium Rate Numbers in Kenya” that consumers are sufficiently informed of the nature, tariff(s), terms and conditions of access of the services using the numbering resource at the time of sale, in advertising and while using the service.”

Licensing and access to USSD

In addition to greater monitoring of USSD pricing, authorities should also be involved in the licensing process at multiple stages. In Tanzania, MNOs, third party providers of value-added services and users such as banks receive USSD short codes directly from the regulatory authorities. By contrast, in Kenya, licensing of USSD services is done by the regulatory authority, but it is the MNOs which issue the codes. Having the issuing of codes handled directly by the MNOs, could leave certain actors at a disadvantage: in cases where direct competitors for financial services are requesting the access codes, the MNO is in an easy position to delay the request or reject it all together.

Authorities in Tanzania note that they have not heard of any issues around the pricing or quality of access to USSD raised to them by firms. This sentiment was confirmed in interviews with stakeholders, who while sometimes raising issues on pricing, did not raise issues on access to USSD codes. By contrast, in Kenya, the issue of USSD code access was raised by several third-party providers as a barrier to access. This may mean that having MNOs issue the codes directly could be a subtle, but significant, barrier to fair access, and that authorities should be involved in the licensing and short code allocation from start to finish.

Until the day everyone uses smartphones, and conducts mobile banking via apps, USSD will continue to play an important role in fair competition and consumer welfare in digital financial services. It is therefore important that competition authorities become more active in this space to ensure fair access, equal treatment, and sufficient consumer protection.

Read the Brief: Promoting Competition in Mobile Payments: The Role of USSD

Add new comment