We Agree – Life Stages Likely Impact DFS Usage Among Young Women

CGAP's recent blog about data-driven insights on gender and financial services resonated deeply with us at IDEO.org. The article summarized several gender-related differences in financial services in South Africa and Kenya, including data points on how formal financial services adoption flattens out for women starting in their early 20s. These insights align with many of our qualitative and quantitative findings from the Women and Money program.

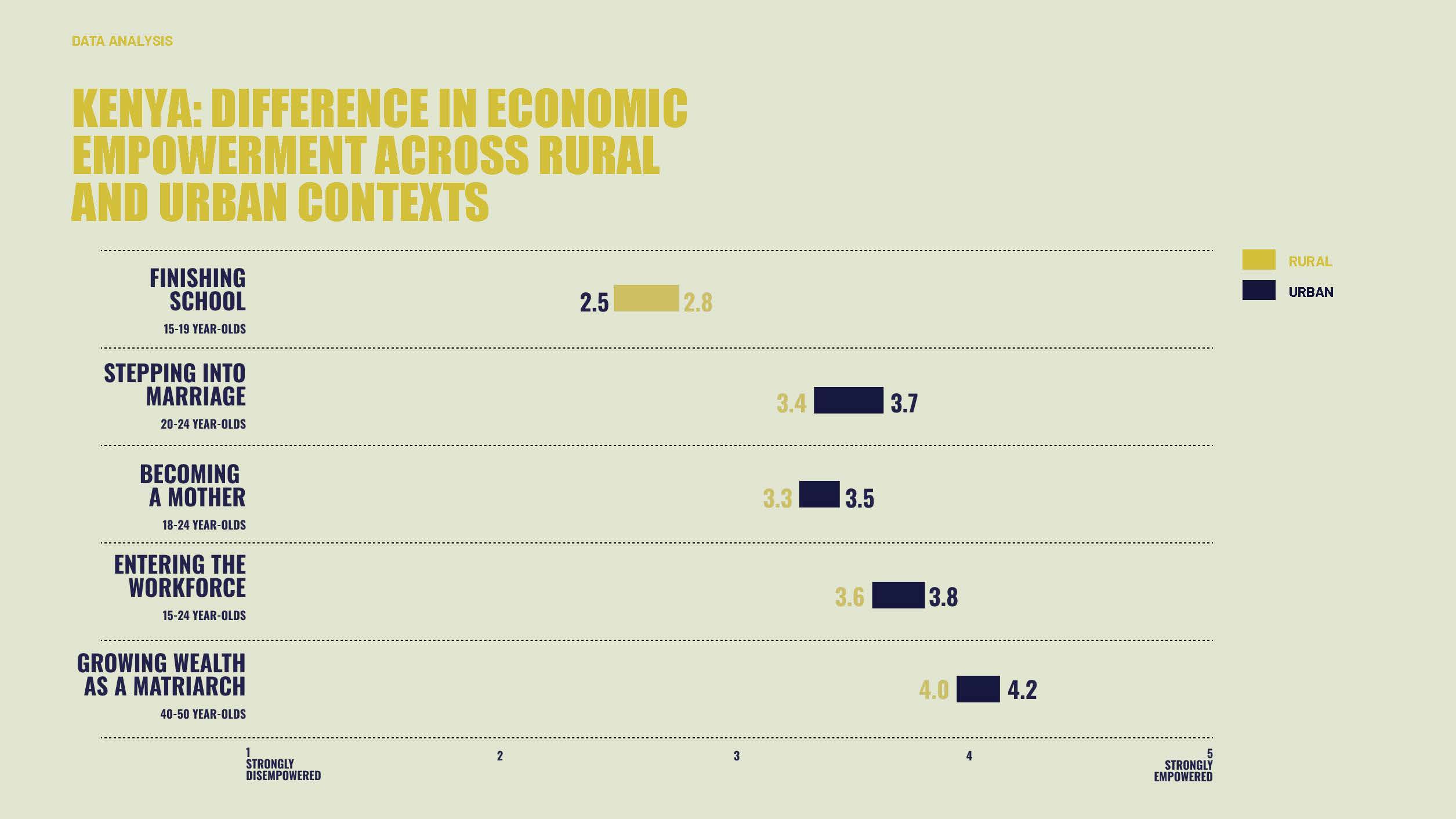

Through our research on the Women and Money program we saw how certain life stages had a significant impact on women’s economic empowerment and financial service use. What is a life stage, you ask? To answer this question, our extended team, including DrivenData and Kore Global, ran a quantitative analysis of country datasets in Nigeria, Kenya and India, conducted a literature review and held four roundtable discussions with over 100 gender experts. These analyses allowed us to identify five important moments of transition in women’s lives:

- Staying in school

- Entering the workforce

- Stepping into marriage

- Having a child

- Growing wealth as a matriarch

We believe these life stages are pivotal for design and women’s equality — whether the shifts are through policy, products or societal norms.

Women in their early 20s often experience several life stages simultaneously, including marriage, entering the workforce and becoming a mother. The median age of a woman’s first birth is just over 20 years in Nigeria and Kenya, and the median age for marriage across multiple African countries is 21-22. Each of these experiences comes with a set of implications for women’s use of financial services and economic participation, but the fact that the life stages are compounded for many women leads us to believe that their impact on decreased formal financial service usage is even more dramatic.

Recently married women’s and new mothers’ DFS usage is lower than at any other life stage

CGAP’s article identified that in South Africa and Kenya, account opening for boys and girls rises quickly in their teens but then diverges sharply. In Kenya, adoption of formal savings products flattens for women in their early 20s, but informal use increases.

These insights aligned perfectly with our learnings. In Kenya, we saw that matriarchs use mobile money at a much higher rate than all young women — and the lowest rate of use was among recently married women and young mothers. These women are often joining new households and communities, settling into new roles with their spouses, and experiencing the full force of social norms that assume women’s role as caregivers in the household. These factors limit women’s exposure and ability to participate in financial services.

In our qualitative data, most of which come from long-form in-person interviews, these points were expressed directly by women we met with:

- Motherhood and money can be at odds. Gender differences in labor force participation and employment impact women’s ability to access and manage resources. Despite the fact that young women are in their prime working years, women aged 20-24 have the lowest workforce participation rates. For example, Busara from Tanzania has a small business selling maize. She also takes care of her two children, cooks all the meals for her house, does all the laundry, decides on purchases for the household, and manages the money her husband gives her as table tax to save in her local upatu ("merry-go-round" group). If she has too much on her plate, her business is the first thing she sacrifices. It will always be her foremost responsibility to take care of the household.

- Gender norms limit mobility and earning potential. In our research for Women and Money, we saw that for many women, a marriage might mean they have to quit their job because it is seen as a reputational risk. One of the women we met in Bangladesh, Abjana, stopped working after she got married because it was deemed improper for her to be an earner in the community.

- Home-based informal work makes formal financial services less relevant. Our research also suggests that if women are working during this stage of life, informal work is more likely to be preferred due to the flexibility when balancing with other family needs. Our interviews in Nigeria surfaced that a woman who wanders too far outside of her home (even for work) is questioned for her morality and decency. Further, a woman who works can threaten the position of a man. When women are working from the home, they are most often transacting in smaller increments and in cash-based ecosystems. The value proposition to engage with financial services – even digital financial services – is diminished for these cash-driven small businesses.

These examples illustrate the human dynamics behind the insights surfaced by the CGAP team. There is a need to build solutions that meet women where they are in life and improve access to digital financial services. For example, at IDEO.org we are currently piloting a roving agent model in Northern Kenya in partnership with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, BOMA Project and Pesakit to bring financial services closer to rural women. If safe, private, affordable financial services can come closer to new mothers, newly married women, and women who are running businesses at home, we will see women have greater voice and control of household finances.

Mary Katica is a senior program director and Shalu Umapathy is a managing director at IDEO.org. They lead the Women and Money program, a four-year initiative funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to surface the complex realities that keep women excluded from digital financial services and build solutions that unlock new opportunities of inclusion and build their agency, voice, and influence over money.

Add new comment