How Can Regulators Enable Last-Mile Agent Networks?

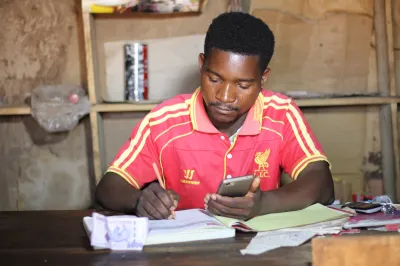

CGAP has been looking closely into one of the toughest challenges of financial inclusion: ensuring access to Digital Financial Services (DFS) in rural areas where most financially excluded people live. Extensive and inclusive cash-in/cash-out (CICO) agent networks are key to solving this challenge. Regulators play an essential role here by enabling DFS providers to innovate agent network models that are sustainable in rural areas.

To be truly inclusive and effective, regulation must balance the risks and benefits of expanding DFS to hard-to-reach regions and clients. This does not often happen. To support innovation and sustainable agent business models, regulators need to be familiar with the types of enterprises, business practices, documentation, and customer transactions (type, frequency, and volume) prevalent in rural markets. With this understanding, regulators can weigh the advantages of easier agent recruitment and monitoring against risks such as fraud, money laundering, and harm to consumers.

Especially important for financial inclusion, regulators can permit DFS providers to recruit rural agents with a variety of profiles and capabilities

When regulation is designed to support low-tier or basic agents, these types of agents can channel entry-level services (e.g., payments, receipt of transfers, simplified credit and savings products) to clients in underserved regions. The most extensive and sustainable rural penetration occurs when regulators ensure that:

-

Providers may recruit agents with low capabilities (e.g., minimal education, basic financial and digital literacy) and from different profiles (e.g., local individuals and shops, fast-moving consumer goods distributors, agro-dealers, or community leaders). It is especially important to include women entrepreneurs. These are what we call basic agents.

-

Basic agents may conduct CICO and distribute entry-level products, including opening simplified accounts.

-

Third-party agent network managers (ANMs) may be shared by various financial and non-financial service providers and aggregate these services under a single agent float account, creating economies of scope and scale that make rural operations viable. This requires regulators to allow DFS providers to decide if they want exclusive or non-exclusive contracts with ANMs.

-

Protections are in place giving consumers confidence that services are safe and appropriate.

CGAP’s research has identified four key regulatory steps to enable far-reaching and inclusive networks

1. Adopt low-tier agent requirements that are proportionate to the (low) risk levels of typical rural financial activities.

Regulation often dictates uniform eligibility and due diligence standards for agents (Know-Your-Agent or KYA). These standards may be based on unrealistic expectations about the capacity and resources of prospective rural agents, and thus prove too stringent in that context. A balanced, inclusive regulatory framework, by contrast, would incorporate risk-based agent tiers and services. This should at least allow basic agents to perform CICO, thereby enabling rural customers to, for example, use their accounts to receive domestic remittances and government cash transfers (G2P), and to pay for public services.

Several countries have allowed for flexible, risk-based KYA by introducing tiered requirements tied to the sophistication of services on offer through different categories of agents. However, CGAP’s in-country experience shows that even the lowest-tier KYA standards are sometimes too high for rural agents to fulfill. For example, agents are often required to be registered enterprises or companies, which excludes most rural entrepreneurs.

Or, they must meet conditions that are common in urban markets but are challenging to comply with in rural areas – such as having fixed premises, established working hours, security protections, and specified types of personnel and outlet infrastructure. These requirements make unfeasible the use of individual and roving agents, who are crucial for outreach in rural areas. Viable agent businesses are even harder when conditions are imposed such as exclusivity (serving a single DFS provider) or dedication (cannot engage in non-DFS).

Another complexity of KYA, beyond getting the formal requirements right, is ensuring that the verification processes and standards are not overly demanding or imprecise. KYA rules often require prospective agents to produce a business registration, tax ID, police record, or other documents. Access to this kind of documentation may be difficult, time-consuming, and in some cases perhaps impossible. Some countries like India eased these constraints by allowing agents to operate during a grace period pending complete verification. Further, when faced with imprecise rules on KYA documentation, DFS providers often err on the side of strictness (imposing a higher than necessary standard of proof) to avoid potential scrutiny by the authorities – in effect, tightening constraints on access still more.

2. Enable DFS providers to exercise some discretion when managing risk in rural contexts

DFS Providers have a more direct exposure (relative to regulators) to the risks faced in rural financial markets. Therefore, allowing DFS providers to have a wider margin of discretion in setting KYA requirements may strengthen the market by enabling providers to pursue strategies consistent with their assessment of opportunities and risks. Setting strong liability and penalty provisions in regulation encourages them to closely monitor their agent networks (directly or through a trusted third party, like ANMs). This incentive structure may be more effective in containing risk in small last-mile DFS transactions than regulators setting rigid limits on definitions of low-tier agents.

Nonetheless, in other contexts where negative country risks assessments have been made, this approach could create uncertainty and result in providers adopting a conservative, risk-averse stance. Last-mile services may be put on hold if regulators fail to clarify the rules. Therefore, regulators should always discuss the intent of their approach to agent regulation transparently with the financial industry even if this regulation is clear on paper.

No one model fits all contexts. In countries where regulatory capacity is relatively low and perceptions of risk comparatively high, a detailed framework that constrains provider discretion may be appropriate. In contrast, more open and discretionary frameworks may be suitable in settings where capacity is high, risks are well understood, and communication channels between providers and regulators are well established (as in India, Brazil or Colombia). In either case, some reality-testing of tiers and due diligence standards is necessary to avoid unduly constraining access.

3. Allow for non-traditional partnerships and Agent Network Managers (ANMs)

Distribution of DFS can gain scale and efficiency when providers bring in third parties to contract or manage retail-level agents. This requires regulators to enable wholesale-level agents, often called master agents or ANMs, to recruit individual agents. Thus, a basic agent might lack the capacity (or fail to meet KYA standards) to operate on its own but can serve under the master agent’s legal umbrella, as we see happening in markets like Cote d’Ivoire.

Further, regulation should provide for ANMs. They may be permitted under general outsourcing rules in banking law or by explicit ANM provisions in digital finance regulations. These firms bring expertise, efficiency, and scale in supervising and supporting agent networks (e.g., through training, liquidity management, and service aggregation). A provider may partner with an entity that owns or has access to a large existing network (banks have long distributed services through big store chains while payment providers have joined up with telcos). Increasingly, DFS providers are partnering with digital platforms that distribute financial services along with consumer goods or agricultural products. Providers plug into a modular agent network that the platform offers to any number of DFS and other businesses.

Newer ANM models need the ability to outsource agent management functions and aggregate financial and non-financial business. These business models, with such features as consolidated float accounts for agents, integration of the ANM’s systems with the DFS providers, fee-sharing provisions, etc., depend on regulatory flexibility. Colombia and India have been successful in applying such an approach.

4. Alleviate constraints in the general “doing business” environment

General conditions for establishing and operating small enterprises have a major impact on agents. The friction encountered in complying with local regulations or obtaining credit, for example, can play a critical role in the agent’s viability. A combination of financial regulations and tax policies may impose excessive burdens on basic agents (e.g., to produce fee receipts or withhold transaction taxes) and increase DFS providers’ costs. The pool of potential agents may be reduced where women face legal and social constraints to becoming agents, which in turn discourages potential female customers. Lack of interoperability may reduce volume, scope, and therefore viability. Regulation often cannot address these issues directly but can reduce their impact. For example, formalization requirements (including registration and proof of tax compliance) can be simplified, at least while agent networks are emerging. Regulators can also encourage the inclusion of women by publishing gender-disaggregated data.

The urgency of agency

Given the importance of rural agents to digital financial inclusion, it is striking how difficult it can be for a rural agent to sustain a viable business. This is especially clear where regulation fails to allow for basic agents (or unduly constrains them), where network manager support is lacking, and where the local business environment is adverse. For these reasons, ‘last-mile’ agents deserve serious consideration at regulatory and policy levels. This means careful periodic review and revision of regulatory frameworks, open to experimental approaches such as pilots or regulatory sandboxes. Authorities should, as a high priority, set enabling conditions and incentives for providers to go rural and for agents to reach those customers who remain underserved or excluded.

For more details on CICO agent regulation, please see CGAP's "Agent Networks at the Last Mile: Implications for Financial Regulators" research.

Resources

Rural agent networks are critical to “last mile” financial inclusion.

Add new comment