FATF's Proposed Rules for Payments: Balancing Integrity and Inclusion?

It is impossible to entirely rid the global financial system of money that’s been involved with crime or terrorism in some way. There is, however, a lot that can be done to identify and combat money laundering and the financing of terrorism in the formal market. The question is, what is the price to pay for a high-integrity system that combats these abuses effectively, and who pays that price? The phenomenon of international banks withdrawing from “high-risk” regions not deemed profitable enough to justify the required compliance expenditure – known as de-risking – leaves those living in such geographies underserved and financially excluded. This trade-off between integrity and inclusion poses a continuing challenge to policymakers.

The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) – the international standard-setting body responsible for anti-money laundering and anti-terrorist financing (AML/CFT) standards – is now seeking the right balance between integrity and inclusion as it revises its Recommendation 16. This Recommendation sets international standards on the information that must be included in payment messages and is known as the “travel rule”. Whatever the final revisions are, they will have a bearing on the accessibility of payments for low-income customers. It is therefore critical that the financial inclusion community makes its voice heard and supports the FATF in this delicate revision – a process that should ideally also be informed by a regulatory impact assessment.

What is the travel rule and how is it changing?

The travel rule was first adopted in 2001 in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks. The current standard focuses on wire transfers and requires that accurate information about the sender (the originator) of funds remains with the transfer throughout the payment chain (see Figure 1). The data is intended to support the work of law enforcement and financial intelligence units and also crime combating by financial institutions. Originator (sender) data is verified by the initial (ordering) institution while beneficiary data is verified by the beneficiary’s (receiver’s) institution.

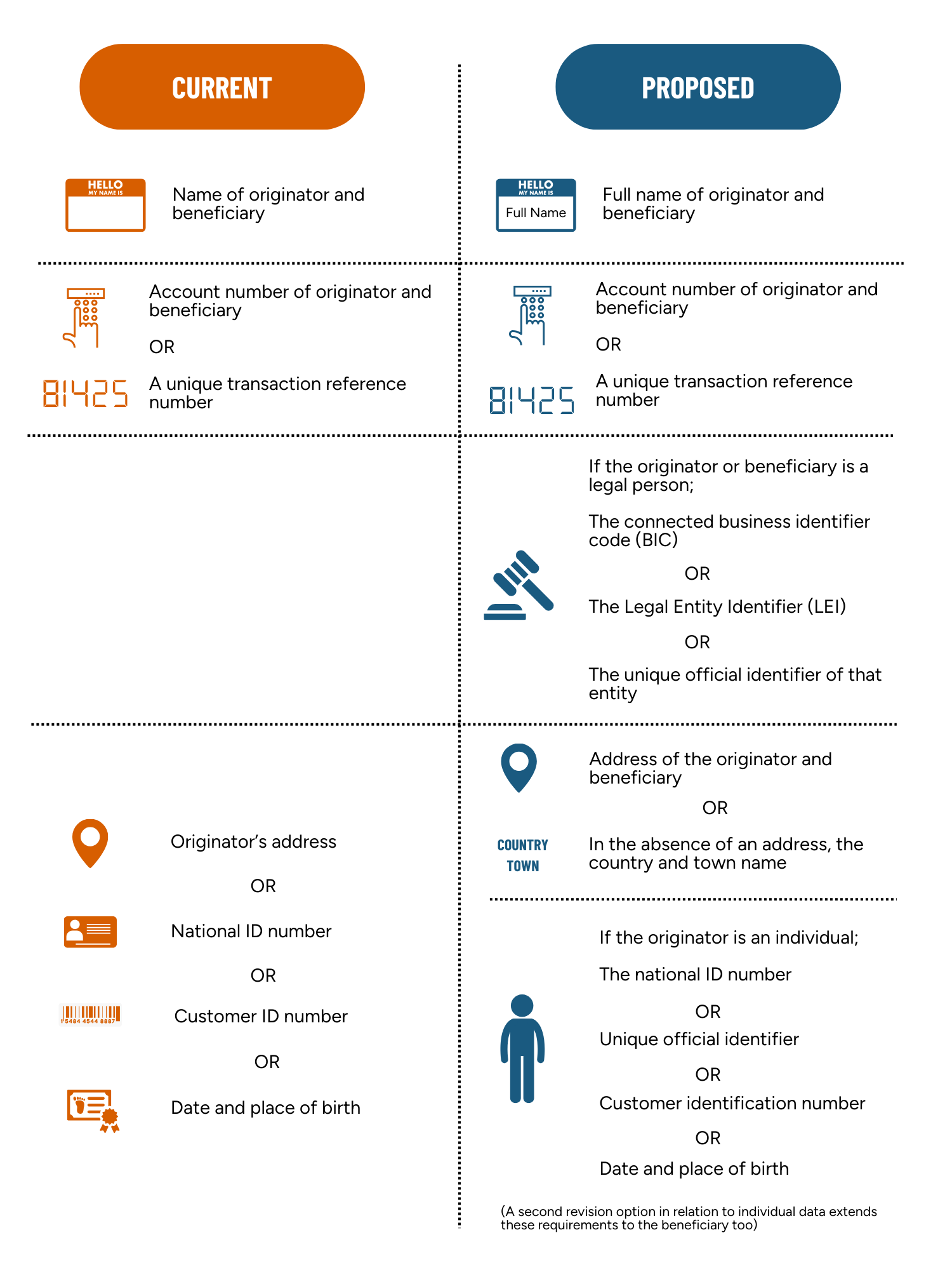

Figure 1: Example of current “travel rule” standard that requires accurate information about the originator of funds to remain with the transfer throughout the payment chain

The standard requires revision to ensure it remains relevant for the emerging payments environment that itself has dramatically changed over the last two decades. The FATF released its proposed draft revisions in February 2024, calling for feedback by May 3, 2024. The proposed revisions would, for example, extend the Recommendation to include credit, debit, and prepaid card-based cash withdrawals. The standard would apply to domestic card-based transactions with a withdrawal value of USD/EUR 1,000 or more, and to all cross-border withdrawals, regardless of value. It would also require more customer data to accompany payment messages (see Figure 2).

The proposed revisions raise important questions about costs and benefits, including possible unintended consequences for the financial inclusion of low-income customers. To illustrate the point, imagine as an example a migrant worker attempting to withdraw foreign-earned money from an ATM in their home country. This migrant may now face additional hurdles. For instance, they may first have to open an account with the institution that controls the ATM to allow for identity verification by that very institution. Such barriers and costs could negatively impact the productive use of remittances for sustainable development and the well-being of migrant workers’ families in their home countries.

Proposed restrictions to the rules regarding card-based purchases of goods and services provide a further example of the potential negative impact on financial inclusion. The revisions will limit current exemptions of such transactions to purchases from merchants only. The draft definition of ‘merchant’, however, may leave many types of entrepreneurs either subject to stricter rules or labeled as high risk, including smallholder farmers who do not engage in 'the regular provision of goods and services' or microentrepreneurs that use their personal accounts to conduct business and have therefore not been onboarded as a merchant by their financial institution.

Figure 2: Summary of current data fields for cross-border wire transfers and proposed changes

The FATF acknowledges that the new measures may be costly and could create unintended consequences for inclusion objectives such as the hypothetical instance above. Importantly, it is well understood that the negative impact on inclusion may be more significant in low-income countries. Those countries often have high exclusion rates and lack reliable official national identification systems, leaving many users without data that can be readily used in identification. In these countries, for instance, a legal entity identifier (LEI) may be inaccessible or prohibitively costly for micro and small enterprises (MSEs). And, while technology now allows for alternative means of compliance with AML/CFT requirements (e.g., by collecting alternative data), our experience suggests that providers tend to over-comply rather than experiment with new solutions. They also tend to collect more rather than less data, for instance, by insisting on recording the national identity number, customer identification number, and date and place of birth of the customer, when the standard requires only one of those data points to be collected.

Forming appropriate perspectives on the implications of the proposed revisions is difficult, as the measures may impact people differently in different countries. To get a better sense of such variability in impact, we need to ask what specific requirements mean in each context (see Table 1 below for some such questions). Answers to these questions would inform a better assessment of the impact of revised Recommendation 16.

Richer customer data fields: country infrastructure and implications for users | |

| Full name |

|

| Address |

|

| Unique number |

|

| Legal persons |

|

Before any decisions are made, a regulatory impact assessment is needed

Let us be clear – the revision of Recommendation 16 is welcome. It is important to ensure that the standard appropriately supports integrity in the current market, especially in light of changes in cross-border payment architecture. The public consultation and engagement regarding the proposals are welcome, too.

A revised Recommendation 16 will, however, affect a significant number of payments and customers for many years to come. It is therefore important to ensure that the drafting process is sufficiently informed to avoid requirements that would unintentionally undermine financial inclusion policy objectives. Therefore, it is of utmost importance for the financial inclusion community (providers, NGOs, funders, customer organizations, etc.) to participate in the consultation process, voice their concerns, and offer alternatives to the current revisions informed by their experience on the ground.

Equally important is that FATF and its stakeholders support a regulatory impact assessment, tailored for a global standard-setting process. That assessment should consider how richer travel rule data will benefit crime combating and impact data protection, cyber security, competition, and financial inclusion. Once adopted, the standard should be subject to an annual review to determine whether its objectives are achieved and whether the benefits outweigh the costs.

Add new comment