Social Assistance Payments in Response to COVID-19: The Role of Donors

COVID-19 BRIEFING: Insights for Inclusive Finance

|

To mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, countries worldwide are working to provide people, particularly low-income and vulnerable individuals, with financial aid. Financial aid delivery relies on social protection and payments systems and the extent to which these are already in place and functioning effectively. This Briefing addresses how donors and their partners can design and implement social assistance payments that are efficient and secure while providing recipients with reliable, convenient, and safe access to their payments. Although it focuses on short- to medium-term response, this Briefing also considers the importance of the longer-term development objectives of building more resilient and responsive digital payments systems. |

Countries worldwide are using social assistance payments as a component of their response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Governments are creating new—and adapting current—social assistance payments programs to include a wider swathe of the population, increase benefit amounts, advance future payments, add extra payments or increase their frequency, or waive conditionalities. According to World Bank estimates, government-led social assistance payments in response to COVID-19 have globally benefited 1.8 billion people, including 1.1 billion new social assistance payments recipients.1

At the same time, humanitarian agencies are deploying cash and voucher assistance to support the immediate needs of households and communities and to help local markets function (CaLP 2020). If and when government programs are launched, the humanitarian programs may complement these or be discontinued.

A key element of social assistance payments is the delivery of financial aid from the government or humanitarian agency (i.e., the sender) to the intended recipients. Senders face a set of choices when making these payments, ranging from physical distribution of cash or vouchers to direct payments into recipient bank accounts. The options depend on a country’s infrastructure and its level of investment in digital financial services. (See Box 1 for a description of how the term “social assistance payments” is used in this Briefing.)

The COVID-19 crisis has shown that countries with well-developed social protection systems, payments infrastructure, and wide access to digital financial services are able to channel social assistance payments more quickly than other countries. For example, in Chile, the national ID-linked basic account CuentaRut allows emergency COVID-19 payments to be sent directly into the bank accounts of more than 2 million vulnerable people. In Thailand, the government uses its interoperable payments system, PromptPay, which allows payments to be sent to a recipient’s ID-linked bank account. Similarly, in Kenya, COVID-19-related payments are paid quickly and directly into recipient accounts and mobile wallets thanks to the country’s wide-reaching digital payments infrastructure.

|

BOX 1. Our definition of “social assistance payments” In this Briefing, the term “social assistance payments” refers to financial aid distributed by governments and/or humanitarian agencies to help individuals and households pay for their basic needs. Social assistance payments might be delivered in the form of vouchers or fee waivers for the purchase of goods and services or through a physical or digital financial transfer. The term encompasses a range of commonly used phrases, including cash transfers, cash and voucher assistance, and government-to-person (G2P) payments. It excludes in-kind assistance such as food and clothing. Social assistance also may be referred to as social welfare or social safety net programming. |

The pressing need for fast and secure social assistance payments during the COVID-19 crisis has built the political momentum that allows some countries to leapfrog to more efficient digital payments systems. For example, the Central Bank of Jordan relaxed its regulations to allow for online account opening with simplified know-your-customer requirements. Regulators in Peru and Ecuador also adjusted their regulations to allow for remote account opening on mobile phones and at agents. While regulations may quickly be passed in an emergency, thoroughly implementing new regulations takes time and infrastructure cannot be built overnight. It is possible that the urgency of the crisis means some programs revert to older, nondigital systems that are seen to be more reliable in the immediate to short term.

Payments delivery

Social assistance payments can be delivered through physical distribution of cash or through some form of digital payment, either in part or in full. A digital payment requires recipients to have a payments instrument that enables them to access and use the financial aid. Some payments instruments, such as vouchers and cards, require physical distribution, while digital instruments, such as mobile vouchers, QR-codes, and one-time passcodes, are delivered through mobile phones.

Physical distribution of cash. Recipients gather at cash distribution points or, in situations that involve vulnerable populations, financial aid may be delivered to or near a recipient’s home. Transporting the cash may be outsourced to specialized companies, moneylenders, or local law enforcement, among others, depending on the context.

Partial digital payments (no recipient account). Recipients receive a physical or digital voucher, scratch card, prepaid card, token, or passcode that allows them to purchase goods, pay for essential services, or withdraw cash over the counter. The payment is digitally transferred to the merchant, utility company, or cash-out provider (i.e., the services provider) after a social assistance recipient has claimed her goods, services, or cash. A purchase or cash withdrawal usually involves verifying the recipient’s identity and/or using a personal identification number (PIN). Recipients may be required to use or cash out the full payment amount or may be able to store funds and use the same payments instrument several times. Some payments cards, such as smart cards, can be reloaded with funds and used for other or subsequent social assistance payments.

Fully digital payments (deposit into recipient account). Payment is made directly from the sender into the recipient’s account at a financial services provider (FSP), such as a regulated financial institution or a mobile money provider. The FSP may provide the account holder with a payments instrument, such as an automated teller machine or debit card, or payments application, such as a mobile money app, for withdrawals and merchant payments. Digital payments into a recipient’s account have the advantage of being more direct and, therefore, less vulnerable to leakage. They also provide recipients with more flexibility in accessing and using their payments at their convenience, and allow them to save part of their payments until needed. Deposits into accounts also may encourage recipients to use digital payments, and less cash, in the medium to longer term.

Because measures to contain COVID-19 have constrained physical mobility and personal interactions, physical distribution of cash and payments instruments have become riskier and more difficult (Haque, Shamsuddin, and Saltmarsh 2020). Digital payments methods, especially payments into recipient accounts, and the use of digital payments instruments are faster and safer than cash distribution. However, in cases where recipients live far from distribution points, do not have reliable mobile connectivity or access to mobile phones, or face other barriers to conveniently access and use digital financial services, complementary physical distribution of cash may be needed.2

Payments process

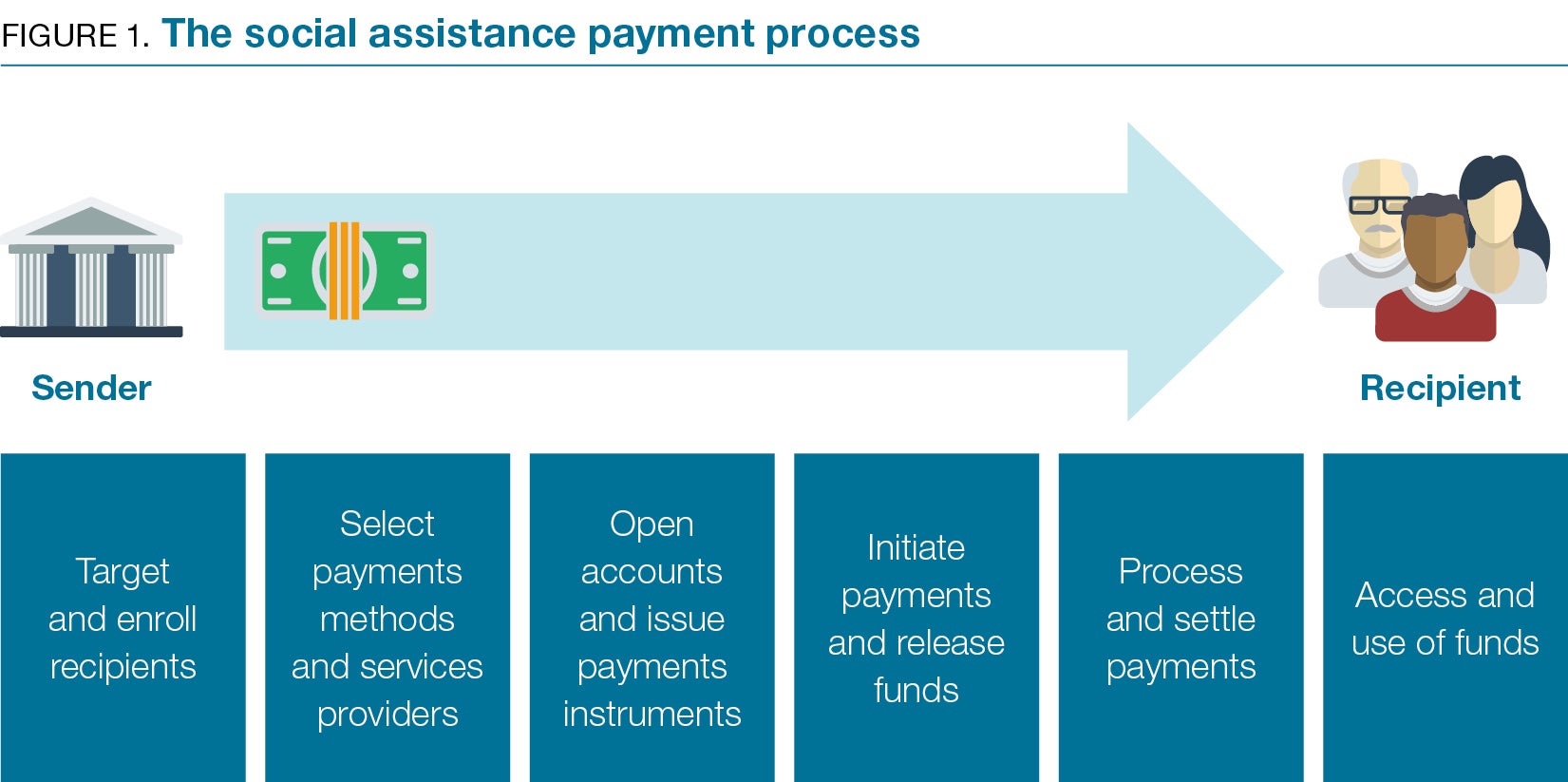

Regardless of the method used, the goal of a social assistance payment is to facilitate the transfer of value from a sender to a recipient in an efficient and secure way that offers the recipient reliable, convenient, and safe access to their payment. The process of sending social assistance payments from senders to recipients entails the following steps:

- Target and enroll recipients.

- Select payments methods and services providers.

- Open accounts and issue payments instruments

- Initiate payments and release funds.

- Process and settle payments.

- Access and use of funds.

This transaction between the sender and the recipient relies on a set of support functions and rules, including informal social norms, that support either, or both, the sender and the recipient and the social assistance payments process. The level to which support functions and rules are developed depends on the context and the payments method. Some support functions and rules may be more important than others; some will be specific to fully digital payments. There is a range of market actors, such as those in the public, private, and civil society sectors, who can perform and pay for these support functions and rules. Support functions and rules can be thought of as a system on their own.3 In describing the process steps below, we have highlighted (in bold) some important social assistance payments support functions and rules that are particularly relevant during the COVID-19 crisis.

1. Target and enroll recipients. The first step is to determine the target group and selection criteria, then identify and enroll recipients. Senders often rely on social registries to identify recipients. However, these registries may not be up to date or may not include people targeted for COVID-19 assistance, such as those who lost employment or became sick, informal workers, and others. Therefore, the registries will need to be complemented with information from other databases that can serve as proxies, such as tax registries, health registries, or alternative data sources, including data on the use of utility and telecommunications services (Rutkowski 2020; Blumenstock 2020). Enrollment also involves verifying recipient identity, which usually is done through a national ID system or some type of proxy identification when national ID documents are not available. Once enrolled, recipient household and payments information usually is managed in a program management information system (MIS).

2. Select payments methods and services providers. Once recipients are identified, senders need to assess which payments methods and services providers are most appropriate and effective for transferring the payments. More than one payments method may be required to accommodate various recipient needs, and several services providers may be preferred or required, depending on the context. This step typically involves procuring and contracting services providers, though this may not be required if senders can leverage a services provider network or payments scheme that already is in place (Baur-Yazbeck, Chen, and Roest 2019). Whether a sender has to launch a public procurement also depends on public sector procurement rules. Market research about recipient access to bank accounts and mobile wallets, recipient access to and familiarity with mobile technologies, and recipient household location in relation to services provider access points can provide useful information for selecting an effective payments method. Social norms, such as consumer perception of cash and digital money and gender inequalities, can heavily influence the selection of suitable payments methods. Mobile infrastructure and connectivity are key enablers for digital payments methods and instruments.

3. Open accounts and issue payments instruments. Recipients need to be given the tools to receive, access, and use their payments. Depending on the payments method and the recipient’s current access to accounts and payments instruments, this step may involve opening accounts or mobile wallets and issuing payments instruments. Opening an account involves a customer due diligence process in which an FSP collects and verifies detailed information about the customer. Senders can help FSPs in this process by providing information about recipients and supporting initiatives for remote account opening (Jenik, Kerse, and de Koker 2020). Senders also may support the distribution of physical payments instruments, such as vouchers or payments cards. ID systems are important tools that will help to verify a recipient’s identity for account opening or distribution of payments instruments.

4. Initiate payments and release funds. To initiate a payment, a sender needs to have an authorized budget and access to the funds. In the case of G2P payments, this step may involve transferring funds from the government treasury or donor into the sender’s account.4 In a second step, the sender needs to identify ways to transfer funds from its account to recipient accounts—in the case of a fully digital payment—or to a services provider’s account—in the case of a partially digital payment. Senders may be able to initiate a payment through a single command in their MIS. However, in most cases, more than one step and several people are involved in the process of initiating payments and authorizing the release of funds into the financial system.5

5. Process payments. The FSP needs access to the sender’s source of funds, either directly or indirectly, through a third-party provider or a payments scheme.6 Depending on the payments method and program design, payments may be processed before or after a recipient accesses and uses her social assistance payment. In partially digital payments, the payment usually is processed once the recipient makes her purchase, bill payment, or cash-out request. Senders may prefer this arrangement because it allows them to maintain ownership over the funds until the recipient accesses—and uses—the full amount. In fully digital payments, the time needed for the payment to become available in the recipient’s account depends on the arrangement made with FSPs and the functionality of the payments and settlement systems used. A real-time payments switch can process payments within minutes or seconds. In an ideal scenario, recipients are notified as soon as the process is completed and funds are available for their use.

6. Access and use of funds. The ultimate goal is for recipients to either use their social assistance payment at an acceptance point, such as a merchant for the purchase of goods or a utility provider for the use of fee waivers; transfer it to another account; or convert it into cash. To access and use their funds, recipients need to identify themselves and authenticate the transaction. This may be done with a payments instrument, an identification document, a passcode, or a PIN. To convert their digital money into cash, recipients need to access an FSP branch, ATM, banking correspondent, or mobile money agent. These access points are managed by cash-in and cash-out (CICO) networks, which may be managed by FSPs or nonbank distribution networks, such as fast-moving consumer goods and e-commerce (Hernandez 2019b). It is important that senders understand CICO networks’ business models and incentives to reliably and fairly serve recipients. This last-mile distribution is one of the most important and most expensive steps of the payments process because it involves liquidity management—availability of cash at every CICO access point. It also strongly relies on consumer education. Recipients need to understand the eligibility criteria, payments dates, payments methods, where and how to access and use their payments, and available customer support and recourse mechanisms. Adequate consumer protection frameworks and recourse mechanisms are important to protect recipient rights.

COVID-19-related payments objectives and the role of donors

Donors have a variety of funding mechanisms and a range of potential partners to support social assistance payments (see Box 2). Context and the donor’s remit and development strategy will determine which mechanisms and partners are most appropriate. Regardless of the mechanism, the goal remains the same: efficiently and securely transferring value from the sender to recipients to offer recipients reliable, convenient, and safe access to their payments.

While there is a range of objectives for building robust, integrated, and customer-centric payments systems over the medium to long term, the response to the COVID-19 crisis has highlighted the need to focus on four key objectives:7

|

BOX 2. Donor mechanisms to support social assistance payments

|

- Ensure recipients’ diverse needs are considered as caseloads rapidly expand.

- Reduce crowds at payments access points to lower risk of virus transmission.

- Help providers prepare for and manage a growing number of cash-out requests.

- Coordinate and collaborate with the government, other senders, and the donor community to respond quickly and efficiently.

OBJECTIVE 1. Ensure Recipients' Diverse Needs are Considered as Caseloads Rapidly Expand.

The need for a rapid response and expanded recipient caseloads should not mean that the design of social assistance payments cannot thoroughly consider all recipient circumstances. Those who were vulnerable before the COVID-19 crisis are now even more vulnerable, while other groups have become vulnerable as a result of the pandemic. Many social assistance programs target women, but the payments process is seldom designed to meet their needs and capabilities—and this is especially noticeable during crises. Experience from the Ebola crisis in West Africa and the earthquake in Haiti, among others, has shown that the “tyranny of the urgent” often sidelines gender (Smith 2019).

It is important to consider that women are more likely to lack access to identification, financial accounts, and mobile phones, which are needed to receive digital payments (Gelb and Mukherjee 2020a, 2020b). Women, especially those who are pregnant or lactating, and people who are elderly, disabled, and burdened with underlying health conditions have special needs and can be more vulnerable to falling ill from COVID-19. If the chosen payments method does not work well for all recipients, it can negatively affect their experience. Even more damaging, it can make them susceptible to fraud because they may need to ask others for help, or it may lead to exclusion because they are unable to access their payments. The overall pressure on the payments system and the psychological pressure on people during the crisis may cause unfair treatment of vulnerable groups and elevate risks of fraud (Neyra 2020; Medine 2020).

What can donors do to advance Objective 1?

- Support and advocate for inclusive and gender-sensitive payments methods. For example, support the collection of gender-disaggregated data and information about the specific needs and circumstances of the target group (Chamberlin et al. 2019; Hidrobo et al. 2020).

- Advise senders and financial sector regulators on using proxy identification for enrolling and opening accounts for recipients without access to national ID documents (Cooper et al. 2020).

- Advise senders on payments methods that offer women and other excluded groups privacy and convenience (Holmes et al. 2020).

- Support market research and facilitate information exchange with FSPs and distributors to understand recipient access to CICO distribution networks and voucher acceptance points. Take into consideration that reduced availability of public transportation can make travel more difficult and more expensive for recipients in remote areas. • Promote and share good practice examples of effective consumer protection rules and recourse mechanisms to guard against inadvertent exclusion and ensure that all recipients are supported.

- Promote and share good practice examples of effective monitoring and evaluation processes that focus on recipient experience, including processes for addressing inefficiencies. This is particularly important because of the evolving and fluid nature of the COVID-19 pandemic.

See Box 3 for an example.

|

BOX 3. Objective 1 in action In Togo, the government decided to pay women a higher benefit than male recipients because it recognized that women carry a heavier burden than men, and that women are more likely than men to invest in their household and children’s welfare. This type of design choice may encourage households to have female household heads register for payments programs (World Bank 2020). |

OBJECTIVE 2. Reduce Crowds at Payments Access Points to Lower Risk of Virus Transmission.

To minimize the risk of COVID-19 transmission, it is important to manage crowds at CICO access and voucher acceptance points. Long lines at payments access points are common for social assistance programs; they are exacerbated during the pandemic and may facilitate further spread of the virus. In almost all countries with COVID-19-related payments, there have been reports of recipients queuing for several hours (World Bank and CGAP 2020). Sometimes recipients need to wait under strong sunlight, in the heat, and without seats, which can be particularly burdensome for people who are elderly, pregnant or lactating, disabled, and otherwise vulnerable (Dreze 2020).

Reducing crowds at payments access points means reducing the number of recipients that visit the same access point on the same day and increasing the reliability and efficiency of the cash-out or voucher validation process. It also means senders must improve their communication with recipients and ensure that recipients, especially those that are new, understand their options on when and where they can access their payments. Clear information on eligibility also is important—to reduce the number of consumers who go to an access point only to find they are not eligible for payment through the program and need to request enrollment. Consumer information needs to be communicated through a variety of channels, methods, and local languages.

What can donors do to advance Objective 2?

- Advise on and support the development of comprehensive information and education strategies for both consumers and access point operators so they can learn who is eligible and where, when, and how recipients can access their payments. Information and education needs to include teaching consumers and operators how to interact safely, for example, by social distancing, wearing a face mask, and washing their hands (WFP 2020).

- Advocate for and provide examples of good practice about regulatory measures that categorize payments access points, including CICO networks, as essential business during the lockdowns. Provide clear guidance on permissible business practices and operating hours to ensure that access points remain open during the lockdowns.

- Advise on measures that allow senders to increase the total number of access points available to recipients. For example, CICO access points can be expanded by contracting additional FSPs or opening multi-provider payments systems to more, if not all, providers.

- Advocate for CICO network development, for example, through agent licensing requirements. Provide examples of regulatory measures that enable CICO networks to expand.

- Advise on and help to assess options for staggering payments dates to reduce the number of recipients who are paid on the same day. Where other social assistance programs make payments at the same time that COVID-19 relief payments are made, donors can help programs with overlapping payments schedules to coordinate with each other on when to issue payments.

See Box 4 for examples.

|

BOX 4. Objective 2 in action In Ecuador, the regulator for financial cooperatives relaxed the requirements for operating agent networks and onboarding agents to allow CICO networks to expand. The the financial sector regulators also enabled non-FSPs, such as pharmacies and grocery stores, to become cash-out agents for the government’s COVID-19 social assistance payments. In Jordan, the central bank licensed a new mobile money provider through an expedited licensing process. In Colombia and Ecuador, payments are made on the day of the month matching the last digit of the recipients’ ID number. In Ecuador, the Ministry of Economic and Social Inclusion sequences the payments of its new COVID-19 social assistance payments and other G2P payments programs to spread them out across the month and stabilize cash-out demand. |

OBJECTIVE 3. Help Providers Prepare For and Manage A Growing Number of Cash-Out Requests.

In many areas, digital financial services are not widely adopted among populations targeted for COVID-19 social assistance payments. Recipients often prefer using cash over digital money because they are not familiar with digital financial services, there is limited acceptance of digital payments among local merchants and services providers, or they face restrictive social norms. As a result, they often rely on converting their digital payments into cash at a CICO access point. This reliance on cash is seen even in countries with mature mobile money markets. As the payments infrastructure develops, business models and regulations adapt, and consumers become better prepared to use digital money, more recipients may be ready to accept fully digital payments and to keep them digital.

During the COVID-19 crisis, FSPs may not be able to disburse social assistance payments at fees that were viable before the crisis, given the added pressure on their systems. The increase in social assistance caseloads and transfer amounts add pressure to their CICO networks’ cash flow—their liquidity management system. Liquidity relies on bank branch operating hours, physical mobility, and economic activity—all of which are being restricted during the lockdowns (Hernandez and Kim 2020).

New service protocols and recommendations, such as disinfecting devices and using masks and protective shields, may involve additional expenses that reduce CICO networks’ commercial interest to provide good and reliable customer service (MSC and Caribou Data 2020). In some countries, FSPs have reduced or waived transaction fees during the COVID-19 crisis, both voluntarily and per regulatory mandate. The resulting revenue losses, if enforced for extended periods, could jeopardize the long-term stability of CICO networks in some countries and put them in a more vulnerable position in future crises.

What can donors do to advance Objective 3?

- Facilitate dialogue between senders, government stakeholders, FSPs, and CICO network managers to identify solutions that are viable for the CICO business model.

- Support data gathering and the development of data analytic tools to help providers and CICO operators effectively manage liquidity.

- Help gather and analyze data on the impact of the crisis on CICO networks to inform senders and FSPs how they might temporarily support the networks and ensure they continue operating during the lockdowns (Hernandez and Kim 2020).

- Provide technical advice and facilitate negotiations for enabling interoperability between CICO networks to allow recipients to access their payments through thirdparty providers and thus spread out cash-out demand. Also advise on, and potentially subsidize, temporary reductions in or removal of cash-out fees for accessing funds through third-party CICO networks.

- Advise on introducing fully digital payments where possible and appropriate, and support consumer information/education campaigns that encourage recipient use of digital financial services, thus reducing recipient reliance on cashing out.8

See Box 5 for examples.

|

BOX 5. Objective 3 in action In Colombia, the government created a “situation room” where government and private sector stakeholders regularly meet as part of a participatory decisionmaking process and co-creation of solutions that work for recipients. Together, the stakeholders decided to eliminate ATM withdrawal fees, including fees for using a third-party ATM, to give recipients a greater choice of access points. The Central Bank of Jordan dropped the interchange fee on mobile wallet transactions and required all mobile money providers to offer full interoperability through the central JoMoPay switch. In India, the government is offering temporary subsidies to mostly rural agents that are representing state banks, which helps offset the losses they face while operating during the lockdowns. |

OBJECTIVE 4. Coordinate and Collaborate with the Government, Other Senders, and the Donor Community to Respond Quickly and Efficiently.

Senders can be far more efficient in their response and in expanding payments programs or setting up new payments programs if they work together and leverage the payments systems already in place. Other actors from the social protection, financial services, telecommunications, and other relevant sectors may have information about vulnerable populations, including their circumstances, their access to financial services, mobile phone ownership, and mobile connectivity.9

Dialogue also helps participants understand the myriad changes resulting from the pandemic that are important to improving the efficiency and security of transfers as well as the recipient experience. Examples of this include changes in access point availability, opening hours, and movement restrictions.

What can donors do to advance Objective 4?

- Identify important stakeholders and facilitate dialogue to coordinate, collaborate, and leverage knowledge, experiences, and systems.

- Facilitate peer exchange and sharing of experiences with social assistance payments programs and experts from other countries.

See Box 6 for examples.

|

BOX 6. Objective 4 in action Colombia’s National Planning Department, which issues COVID-related social assistance payments, leveraged and expanded on the social assistance payments systems of the Department of Social Prosperity. They also exchanged data with FSPs and mobile network operators to identify recipients with active bank accounts or mobile wallets and to understand recipients’ readiness for digital payments based on their access to mobile network connectivity. In Ecuador, a donor-supported dialogue between financial sector and social protection agencies and FSPs helped identify regulatory barriers to the expansion of CICO networks. In Lebanon, the government is collaborating with a humanitarian agency to leverage its payments system and experience to channel social assistance to vulnerable populations. |

Operating principles for donors

There are several higher-level operating principles for donors to efficiently and effectively support social assistance payments during a crisis like COVID-19.

INTERNAL COLLABORATION

Social assistance payments have become increasingly multidisciplinary because COVID- 19-related responses may include other social assistance, humanitarian, or development efforts. As senders shift to digital payments methods, they increasingly rely on, and contribute to, other development goals, such as digital inclusion, financial inclusion, and access to identity. These usually are managed by specific teams within donor agencies. Therefore, collaboration among various teams within a donor agency can be valuable, yet it can be challenging to accomplish because the different teams may use different terminologies and may have distinct, and sometimes contradictory, objectives.

Collaboration between headquarters and country office teams becomes even more important during the crisis. Decisions about new donor programs or adaptations of existing donor programs often are made at headquarters, while country office teams have access to local intelligence about how things are evolving on the ground. Local intelligence is now essential for making decisions, given the fluid nature of the pandemic and its effects on local economies and populations. Donors also can support their staff by facilitating a regular exchange among country offices for sharing lessons learned and good practices. Capacity building activities may need to be shifted to virtual channels.

THINK LONG TERM AND SEQUENCE INTERVENTIONS

While COVID-19-related social assistance payments may be an immediate or shortterm response to help poor and vulnerable people, medium- and longer-term recovery and development needs should not be overlooked. Short-term interventions should not undermine relationships, business models, or longer-term development strategies. In fact, some COVID-19-related social assistance payments that had been considered one-off or short-term interventions now have been extended and may continue for months.

This represents opportunities to adapt and improve payments systems to become more sustainable and inclusive over time. For example, during the COVID-19 crisis, the benefits of remote and digital interactions and transactions have gained strong momentum, presenting opportunities to promote changes in the market that previously seemed less attainable. Some examples include adoption of basic regulatory enablers for digital financial services,10 remote customer due diligence for account opening (Jenik, Kerse, and de Koker 2020), expansion of recipient choice from among several participating providers (Baur-Yazbeck, Chen, and Roest 2019), and expansion of authorized cash-out networks (Hernandez 2019a, 2019b). Instead of supporting inefficient workarounds, such as reverting to physical distribution of cash, that might have been necessary for the immediate response to the crisis, donors should be helping senders plan and develop a strategy with short-term,medium-term, and longer-term objectives. In the long term, efforts that promote access and use of digital financial services will lead to a faster and more efficient social assistance response to subsequent crises.

USE ADAPTIVE MANAGEMENT

In the face of uncertainty, adaptive management—structured, iterative decision-making processes—and feedback loops enable donors and senders to test a range of solutions for efficiency and effectiveness. During a crisis, there often is no one clear programmatic response that is likely to be sufficient. Donors and senders need to adapt to the local context and circumstances, which may change over time. Interventions for COVID-19 responses require short feedback loops to determine what is having a positive impact and what other responses may be appropriate. Shifting between payments methods and instruments or using more than one in parallel may be necessary to meet different recipient needs or address challenges encountered during implementation

STAY FLEXIBLE IN CONTRACTING AND PROGRAM MANAGEMENT

Given the complexity of the COVID-19 crisis, donors need to keep operating and contracting procedures flexible. Internal approval and reporting mechanisms may need to be revisited and aligned in the short term. For example, donors should consider faster review and contracting processes, shorter contract periods, and more flexibility and ease in amending contracts. Donor and sender compliance requirements may need to be adjusted, too, especially those related to proof-of-payment mechanisms that involve biodata or fingerprints (WFP 2020).

--

1 Based on live data on global COVID-19-related social protection responses, including social assistance payments. See Gentilini et al. (2020).

2 See also Gerard, Imbert, and Orkin (2020).

3 See the CGAP topic, “Systemic Approach to Financial Inclusion,” available at https://www.cgap.org/ topics/collections/market-systems-approach.

4 See also Una et al. (2020).

5 See CGAP case studies from Bangladesh (Baur-Yazbeck and Roest 2019), Kenya (McKay et al. 2020), and Zambia (Baur-Yazbeck, Kilfoil, and Botea 2019).

6 For example, mobile money providers sometimes connect to a national switch through partner banks. In this case, the payment is processed through a third-party bank. The third party also may be a payments aggregator.

7 See Baur-Yazbeck, Chen, and Roest (2019) on building more robust, integrated, and customer-centric G2P payments systems.

8 Over the past decade, donors and humanitarian agencies have been advocating for and supporting the introduction of digital payments methods. See, for example, guidance provided in the Inter Agency Social Protection Assessments Payments Assessment Tool (ISPA 2016) and “Principles for Digital Payments in Humanitarian Response” (GIE 2016).

9 See also Baah and Downer (2020); Barca (2020); Bodewig et al. (2020); Golay and Tholstrup (2020); and Mercy Corps (2020).

To view full list of references, please see PDF.

|

The authors of this Briefing are Silvia Baur-Yazbeck and Diane Johnson of CGAP. The authors thank Estelle Lahaye, Gregory Chen, and Stella Dawson of CGAP for overall guidance. Alice Nègre and Michael Tarazi provided valuable inputs. |