|

Why Consider Interoperability?

As discussed in “Two-Sided Market Problem,” ubiquity of merchant acceptance points is a fundamental prerequisite for the customer value proposition and, hence, for gaining traction with digital payments in the retail space. Customers will make the effort to learn how to use the product, adjust their routines, load and maintain balances in their e-wallets, and actually use them for daily purchases only if enough retailers accept digital payments. Conversely, merchants will maintain active payment acceptance points only if enough customers want to pay digitally. Therefore, success requires gaining significant scale on both sides of the market within a limited time, thereby generating a critical mass that can then sustain itself.

Providers should reflect on the sheer scale required, how best to reach that scale, and the implications of failing to do so. Interoperability is a critical lever to ubiquity that providers can’t afford to overlook.

When it comes to the scale of acceptance networks, it is useful to consider the number of ATMs and point-of-sale (POS) devices for bank cards in developed economies. While obviously an imperfect comparison in several ways, this can nevertheless give us a general idea of the scale of acceptance networks required to get mass market uptake of digital payments. Across the countries in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), POS devices outnumber ATMs between 7 and 25 times. For the sake of simplicity, we can conclude that the ratio is around 10 or more.

This ratio makes some intuitive sense. For instance, it seems reasonable that the number of different shops, restaurants, buses, taxis, and so forth where a typical cardholder pays for things should be at least 10 times greater than the number of different ATMs that same person visits. And for their part, DFS providers in developing markets most likely have similar ambitions in mind for their merchant payments implementations: their customers should pay digitally 10 times as often as they cash out from an agent. Hence for a general sense of scale, the ratio might have some merit.

From this simple comparison we can conservatively generalize that merchant acceptance points may need to be at least 10 times the size of agent networks. Whether the “true” number might be 8 or 12 is less important than the realization of the scale that this brings.

Managing a distribution network is a daunting task, and many providers are likely to balk at the notion of building another network 10 times the size of an already difficult, expensive agent network. Needless to say, developed markets have taken decades to build up those networks.

However, if digital payments are to succeed, providers need to be prepared to tackle this scaling challenge as aggressively as possible.

To achieve the level of ubiquity that this comparison suggests is needed, providers must be prepared to develop millions of merchant touch points. Rather than do this alone, providers should consider interoperability with other actors in the market.

Another critical aspect of interoperability is how it impacts the value proposition for customers. Without interoperability, digital payments are possible only when a merchant and a consumer are using the same provider, which dramatically reduces the number of acceptance points where customers can transact as well as the share of each merchant’s customers that are able to pay digitally.

Customers may become frustrated seeing that some merchants are digital but still cannot accept their payment because of lack of interoperability. The only solution for customers is to sign up for several wallets and load each with a sufficient balance to transact, which is an unappealing prospect.

It is equally frustrating for merchants who are forced to sign up for several schemes—each of which may involve bespoke hardware, processes, settlement accounts, and so forth.

It goes without saying that the lack of interoperability substantially undermines the value of digital payments on both sides by increasing costs and being inconvenient, and it may prevent the market from ever taking off. For more on the customer value of interoperability, see “Interoperability and Customer Value.”

Global Experiences in Interoperability

Market size aside, DFS providers looking to take on the digital merchant payments space would be wise to study (but not simply copy) the experience of bank cards in developed economies. This includes the question of interoperability, for which the card market in the United States illustrates several important dynamics and which even in the U.S. case was not achieved overnight or in a straightforward manner.

From Bank of America to Visa: Trading proprietary advantage for growth

The modern card scheme came from Bank of America (BofA), which mailed out the first credit cards to customers in California in the late 1950s. The so-called BankAmericard became a great success with customers as well as for the bank itself, not least because of the lending revenue it generated. At the time, BofA was restricted by regulation to operating only in California. However, the bank realized that its customers were traveling and spending across the country, so for the card to be truly useful, it had to be accepted nationwide. Since BofA didn’t have a presence in other states, it couldn’t achieve this on its own. The solution was to take one of its most successful products, a leading source of competitive advantage, and franchise it to other banks in different states. This was the start of what eventually became Visa.

The key takeaway for DFS providers today is that although BofA devised the scheme, the scheme was successful because other member banks saw the commercial upside of interoperability. BofA realized that licensing its technology to other banks to develop a major card payments market was smarter than dominating a small and static piece of it. And it was clear to all the banks involved, in both Visa and Mastercard (formed by another group of banks as a competing association), that developing a market as large as the one in the United States required cooperation. In particular, the need to sign up merchants was too large a task for any one card-issuing bank to undertake.

In joining the card associations, member banks surrendered considerable individual control over how these products worked, but they gained the significant benefits of common product definitions and a global acceptance framework that no one bank could have developed on its own.

Citibank and the ATM: Pressing the advantage

In the 1970s, banks in developed countries were beginning to invest heavily in mainframe computing and automated record keeping at central or regional data centers. However, because customers still frequented branches to deposit checks and withdraw cash, banks competed for customers primarily at the branch level.

At the time, Citibank was one of a dozen major banks competing for consumer checking accounts in New York. With fewer branches than some other banks, Citibank had no particular competitive advantage. To gain a competitive edge, the bank decided to adopt ATM technology, which had just begun to emerge. In 1977, Citibank announced that it would “blanket the city” with ATMs and spent around $630 million in today’s dollars deploying the machines across New York.

The investment paid off—partly due to the weather. In 1978, a huge snowstorm closed the whole city down. No bank was able to open to provide customers with cash to buy groceries and other necessities, but Citibank’s ATMs remained open. Citibank immediately released TV ads showing customers trudging through the snow to get their money out and simultaneously introduced its new slogan: “The Citi Never Sleeps.” In the next 10 years, Citibank’s market share went from 4.5 percent to 13 percent, a growth largely attributed to ATMs.

Citibank could have chosen to develop and introduce these ATM’s in consortia with other banks, much like the POS networks for cards that Visa and Mastercard had taken to scale. This would have significantly reduced Citibank’s hardware investment cost and helped spread the burden of customer education and familiarization with the new technology. But the bank put greater value on growing its share of the pie and maximizing the leverage from its newfound competitive edge, which it did to great effect.

Other banks took a different approach. Realizing the investment required to catch up with Citibank’s lead on ATMs, six of its major competitors opted for interoperability. In 1985, they formed a network called the New York Cash Exchange (NYCE) that allowed one bank’s customers to use another bank’s ATM. Citibank soon began to feel pressure from its own customers to also have access to other bank ATMs. For 10 years, Citibank resolutely refused to join the network, believing that its superior ATMs continued to bring it new customers and preserved existing customer relationships. But in 1994, Citibank finally relented and joined NYCE because the lack of interoperability with non-Citibank ATMs was becoming difficult to justify to the bank’s customers.

The key takeaway for DFS providers today is that, while proprietary acceptance networks can create a temporary advantage in the market, even dominant players are often unable to compete with collaborative schemes over time. Citibank did well from its early bet on ATMs, laying a foundation for its position as the leading bank it is today. However, its reluctance to see the longer-term benefits of interoperability ultimately proved untenable.

For more on interoperability, see “Beyond Switches, What Makes Interoperability Work?”

Mobile money in Tanzania: A rising tide lifts all boats

The lessons from cards are echoed in the development of mobile money interoperability in Tanzania, albeit at a faster clip. As addressed in “How Tanzania Established Mobile Money Interoperability,” interoperability among Tanzanian mobile money providers was the result of an industry-led process to establish the business models and operational rules for interoperability across various use cases. Notably, in this very competitive market, the four major mobile money providers active at the time (a fifth has since been added in Halotel) were part of the process.

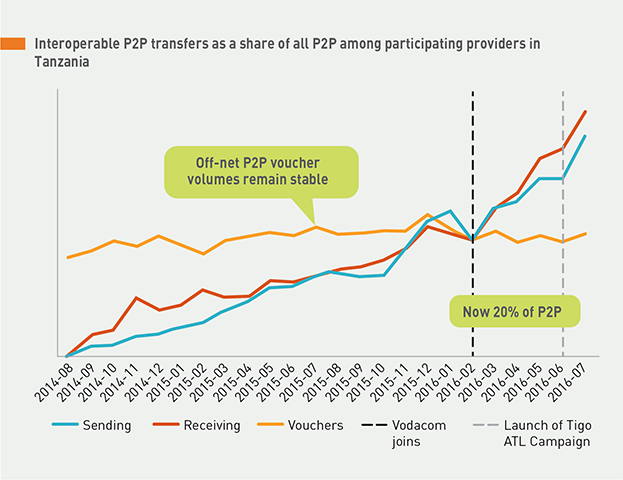

At the end of the process, when the moment came to decide whether to set up and participate in the scheme that the parties had developed, three of the four decided to go ahead, concluding that the gains from growing the market outweighed the risks of losing transactions to competitors. However, Vodacom, the dominant GSM provider with the largest market share in mobile money, stayed out. As person-to-person (P2P) payments across providers in the interoperability scheme grew, so did pressure on Vodacom to participate. After a year-and-a-half, when the participant providers’ share of P2P transfers that terminated with a different provider had reached 15 percent, Vodacom joined the scheme.

The takeaway from this for DFS providers in other markets is two-fold. First, the Vodacom case, like that of Citibank, shows the considerable pressure, even on market leaders, to join an interoperable scheme, which in turn demonstrates the very real advantages of interoperability.

Second, market growth is a very real phenomenon and can happen very quickly, as illustrated by the clear acceleration in the share of interoperable transfers after Vodacom joined the Tanzania scheme (see figure) and by the fact that these transactions are net new transactions, they are in addition to the existing (and rather cumbersome) P2P transfers via cash-out vouchers whose volumes remained stable.

Implications for Competitiveness

The vast majority of digital payments providers will eventually see the benefit of making their platforms interoperable to promote use. And, they may be better off doing so sooner rather than later, especially since the powerful role of network effects in digital payments means that “later” will never come unless they can build sufficient critical mass on their own, which is extremely expensive.

That said, it will always boil down to the economics of the specific market and provider to see what makes sense for them in a given context and point in time. Regulators should not take this to mean that forcing interoperability on providers is a good idea, since the question of regulation is far more nuanced than that. Foisting interoperability on a market in the wrong way—notably with a poor business case for the commercial actors involved—can do considerable harm to the market. For more on the issues around mandating interoperability through regulation, see “Should Funders Support Switches for Mobile Payment Interoperability.”

The most obvious advantages of interoperability to a given DFS provider include (i) reduction in the cost it must incur to establish a large enough acceptance network, and conversely (ii) an improved value proposition for its customers by expanding the number and type of acceptance points where customers can use the merchant payments product. Another potential advantage is the increase in revenue from the providers’ own customers and those of other providers.

Interoperability means that your own customers will transact at merchants “owned” by other providers and that the customers of those other providers will transact at your merchants. Both types of transactions are likely to increase revenue for your business, depending on the acquiring model. Interoperable models that use transaction fees, such as the four-party model used by credit and debit cards, typically generate revenue for both providers involved in the transaction. For example, the credit/debit card model sees the acquiring financial institution charging a fee (a merchant discount rate) to the merchant and then paying a portion of this amount back to the issuing institution via interchange. In this way, interchange balances incentives so that both providers see value in driving transactions within the scheme. See “Balancing the Economics of Interoperability in Digital Finance” for more on the economics of interoperability.

Even in models that do not involve transaction fees (see “Don’t Charge Transaction Fees”) the increased activity will generate data that can be monetized and can improve the usefulness of paid value-added services offered to merchants and/or end customers.

The same benefits accrue to your competitors. Greater transaction volumes mean a larger pie for all, so assuming revenue models are designed well, all participating providers should stand to gain. For more on the revenue model, see “Choosing a Profit Strategy for Merchant Payments Model.”

Despite these advantages, providers often are concerned about the potential negative competitive implications of creating or joining an interoperability arrangement. One of the most common concerns is about other providers free riding on their infrastructure and failing to roll out their own acceptance points. Free riding can indeed be a problem; it can create a market failure in which providers together underinvest in establishing acceptance points. This is particularly the case before a vibrant market for third-party merchant acquirers has been established. While such a market is developed—and providers should consider actively working in that direction from day one—free riding can be addressed by setting minimum requirements on the existing or future acceptance points that each participant in the scheme contributes. However, this is a very blunt instrument that should be used only as a last resort. The best and most effective way to deal with free riding is to get the business case right for the acquiring side of the business. As long as merchant acquiring is profitable enough, free riding should not be a concern.

Providers may also worry that interoperability means that their investment in acceptance points is no longer a competitive advantage that distinguishes them from other providers. This is an understandable concern for mobile network operators because geographic coverage of communications and agent networks is traditionally a key source of competitive advantage. Again, how this plays out depends partially on a combination of the overall business model of the provider and the scheme’s revenue model.

Interoperability can also lower barriers to entry for new providers that want to enter the market, thereby increasing the number and perhaps types of competitors. This applies only to fully open schemes and should be considered part of the short-term costs needed for digital payments to succeed. Providers can always protect themselves from this situation through explicit and implicit requirements for participating in the scheme or by using a statutorily closed scheme or a system of bilateral agreements.

Models of Interoperability

As discussed in “Digital Finance Interoperability and Financial Inclusion,” there are three basic operational models for establishing interoperability in retail payments: bilateral agreement, multilateral agreement, and third-party aggregator.

Bilateral agreement

Bilateral agreements serve to connect two providers directly, creating a tailored link between the two. This solution may seem to many providers to be the easiest path in the short term. However, the model adds cost and complexity at scale. Without common scheme rules, each new participant requires a negotiation around dispute mechanisms, operating standards, interparty economics, and other governance decisions.

Multilateral agreement

A multilateral agreement involves three or more providers that agree on common rules for all participants. A multilateral scheme should not be confused with a financial switch. Three or more providers can agree to a common set of rules, with the actual technical connections for payments clearing executed in any number of ways, as decided by the scheme. These may include bilateral API connections, a central switch, or a third-party aggregator. Yet in practice, the vast majority of multilateral schemes involve a central switch. These schemes can be domestic (e.g., Rupay in India, using the National Payments Corporation of India’s network file system switch), regional (e.g., Southern African Development Community markets, using the Bankserv switch), or international (e.g., Visa and Mastercard using their own technologies).

An essential part of a multilateral scheme is the governance rules that set the requirements for participation, define the key rules and processes, determine how decisions will be made, and ultimately set the terms for how competitors will collaborate. For more on this complex topic, see “Rules of the Road: Interoperability and Governance.”

Third-party aggregator

A third-party aggregator is an organization that offers merchants or customers the ability to connect to several providers who do not otherwise have agreements between them. This model solves the problems of a coordination failure because individual providers sign up with the aggregator on their own terms and timeline and do not need to act simultaneously or establish shared technical or governance standards.

This type of interoperability is common for debit and credit cards, where cards from the various networks (Visa, Mastercard, American Express, Discover, China UnionPay, RuPay, Verve, etc.) are interoperable among participants within each scheme, but not between schemes. Acquirers that participate in several of the schemes can therefore enable their merchants to accept payments from a broader range of issuers without the need for several different hardware, software, merchant accounts, rules, processes, and so forth. These days, most card acquirers participate in several schemes.

There are similar examples outside the card space, including in China, for instance. In China, mobile payments giants Alipay and WeChat are not interoperable; however, merchant acquirers like Wowo Shijie enable their merchants to accept payments from Alipay and WeChat through a single quick-response (QR) code.

Merchant acquirers can unify payment acceptance not just across different issuers of the same type, but across different types of issuers (e.g., bank and mobile money), acceptance technologies (e.g., QR, near-field communications, and the global standard for cards, EMV), and channels (e.g., in store and online). Mature payments markets tend to have a competitive merchant-acquiring space where acquirers differentiate themselves to merchants by creating the broadest and most compelling combinations of issuers, acceptance technologies, channels, and other features.

For more on this and to better understand the roles of different players in the merchant- acquiring ecosystem, see “Acquiring Models.”

Concluding Thoughts

While these models are distinct, it is important to note that they are not mutually exclusive. A given payments provider can participate in several interoperability schemes at once, and in fact, many often do. For instance, multiparty schemes can have a bilateral arrangement between themselves, such as when Nigeria’s card network Verve partnered with its U.S. counterpart Discover to enable payment acceptance at each other’s POS devices. Similarly, it is common for merchants to accept card payments across both Visa and Mastercard through a single merchant aggregator even though these multilateral schemes are not mutually interoperable.

It is also essential to note that the question of scheme type is largely distinct from the question of what infrastructure is used for clearing and settling transactions. But as discussed in “Connecting the Dots: Interoperability and Technology,” while centralized payments switches are often associated with multilateral schemes, the calculus around what infrastructure makes the most sense is in reality more nuanced. Two providers establishing a bilateral scheme can very well agree to clear payments through a switch. Conversely, multiparty schemes can do bilateral payments clearing, as is the case among mobile money operators in Tanzania. For more on this, see “Balancing the Economics of Interoperability in Digital Finance.”

For more resources around interoperability for banks, mobile money providers, and other DFS players, see “Beyond Switches, What Makes Interoperability Work?” which includes an overview of interoperability schemes in 20 countries.