6 Data Protection Rights for Empowering People in the Digital World

The tech revolution is leading to financial services that are more customized to our needs. Driving this revolution are vast amounts of our data that, when combined with digital and analytic technologies, help to create innovative services. Think about robo-advisors that observe our accounts and offer investment advice. Some of these “fintech” innovations are cropping up in emerging markets and focus on expanding access to underserved communities through cheaper, more appropriate financial services. For instance, fintech companies are using satellite and geolocation data to customize insurance policies and payouts for individual farmers. Others are using payment data from women’s savings groups to offer small amounts of credit to customers. These innovations present opportunities to advance financial inclusion, but we must also ensure the security and autonomy of individuals.

Policy makers rightly recognize the need for greater controls to prevent privacy violations in this digital world, and today several emerging markets and developing economies are considering and enacting data protection policies. In an earlier post, “3 Data Protection Approaches That Go Beyond Consent,” we encouraged policy makers to consider going beyond individual consent as the primary basis for data protection. While the concept of consent is fundamental, the choice to accept a set of terms and conditions comes at a time when people are about to access a service, website or app and are, therefore, least likely to consider it fully.

In addition to initial consent, . For instance, what if people had the right to access and correct their information after being denied an account based on inaccuracies in their file? What if after signing up for a service, they were able to move their data to another provider to take advantage of better terms or service offerings? Digital technologies make it possible for people to remain at the center of decisions around their data. The recently enacted GDPR in the EU reinforces the importance of consent but also equips people with other autonomies. And countries like India, Kenya and the United States may be following suit. .

Right to access personal data. Policy makers should grant individuals the right to access their personal data from a data collector and receive it in an easy-to-read format. GDPR requires that people be able to see their data, including which categories of data will be processed and why. In a world of data fluidity, it also requires data controllers to reveal any available information about the source of their data. There are also time limits within which a data controller must make this information available. As with the central banks of many countries, the Reserve Bank of India mandates that credit rating companies provide individuals with one free credit report a year. The Fair Credit Reporting Act in the United States goes further by requiring these companies to inform individuals about who has requested their credit report in the past year.

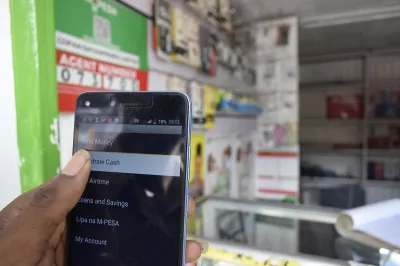

Giving people access to their data can make them more aware of what data are being collected and processed and why. It may also help people to understand and change their behaviors. For example, many payment applications allow customers to see their transaction history, which helps them to understand their spending habits and routinize recurring payments such as bills and subscriptions. A few years ago, M-Pesa began allowing customers to download their transaction data in a few easy steps. This could even be the basis for access to other financial services for the customer.

Right to update your data. Sometimes inaccuracies in one’s personal data may prevent people from accessing important services. This isn’t always due to errors. Sometimes personal data simply become outdated. For instance, someone’s tax filing status and level of education may change over time, and such changes may unlock further benefits if data can be updated. Modern data protection laws must ensure all systems collecting our data are equipped to register changes in a person’s data and that they do so electronically and with relative ease. Article 16 of GDPR not only allows for correction but also the right to complete data that is incomplete.

Right to erase your data. The right to erase one’s data can empower customers to prevent their data from existing or spreading when they no longer consent. While ensuring caveats for security concerns or freedom of information, the right to erasure can allow customers to change their mind about a third party holding their data. This would be relevant when customers stop using a service and no longer wish for their data to reside with the data controller. Or it could apply when providers introduce new ways to use data themselves or through third parties to which the individual does not consent.

Right to port your data. The right to portability goes the furthest in altering the relationship between a data controller and a data subject. GDPR’s right to data portability gives people the right to take their data from one data controller to another. It also mandates that controllers transfer data in a format that is usable by another entity, such as a financial services provider. For example, an M-Pesa customer can take his or her payment data to a bank in Kenya to become eligible for a business account or a car loan. Data portability can have a significant impact on how data-based businesses operate. If customers are not happy with the services they receive, they can more easily switch providers by requesting that the data be sent to a competitor. Portability need not only be for switching services. It can also allow individuals to leverage data from one service (such as payments) and use it to become eligible for other services (such as credit or insurance). This can have significant implications for financial inclusion, through expanded creditworthiness.

Right to object to information use. Even after a person has granted access to their data, they should have the right to reconsider their decision, either after a period of time or for every new kind of use the data controller requests. A key application is the ability to turn off marketing prompts. Another is the option to stop one’s data from being shared with third parties. This is particularly relevant today, when data are increasingly collected for one purpose and deployed for another with third-party applications. GDPR empowers people to object to how their information is used, even after they have provided individual consent. Data controllers will have to abandon all-or-nothing strategies for data use and alert customers on each new kind of processing so they may exercise their choice to opt out. It’s important that customers have the choice to opt out of third-party data sharing just before it happens and not only during sign-up when they are less likely to read terms and conditions.

Rights with regard to automated processing. As technologies like artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) mature, data protection will need to keep up to safeguard customer privacy, including the right to receive an explanation of AI- or ML-based processing and the right to object to decisions made by nonhuman processors.

Are there other ways you would like to see people have greater autonomy over their data in the markets where you live or operate? Please share your comments and questions with us below.

Add new comment