The Business of Aggregators: A Changing Market

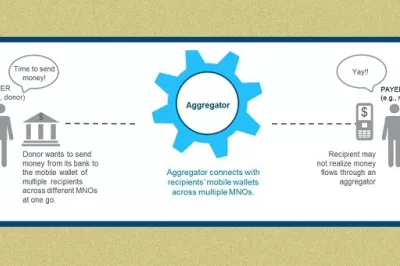

In the digital finance ecosystem, aggregators function as the glue that helps entities like businesses, governments and donors easily connect with a variety of payment platforms--like mobile money services or banks—and the customers who pay via those services. But as CGAP’s deck on aggregators explains, many aggregators function only in the background of transactions and do not directly engage with customers. How do these aggregators get off the ground, what is their size and reach, and what are some key components of their business model?

Aggregators in East Africa started in the telecom or banking industries. Many of today’s aggregators began as airtime resellers for MNOs or backend IT providers for banks. Because of this foundation, the earliest aggregators were companies that already had a certain level of access and credibility among payment instrument providers like banks and MNOs.

As digital payments struggled to gain traction outside of Kenya in the years after M-PESA launched, MNOs were seeking solutions to increase uptake of mobile wallets. Simultaneously, utility companies and other third-party entities were keen to offer customers convenient payment methods - with the ultimate goal of improving collections. But MNO platforms lacked the technical agility and operational bandwidth to lead the integration with multiple third parties themselves. This gave rise to a role for aggregators.

Today, the aggregation business is booming. For example, our interview with Pegasus in Uganda revealed that the company processes nearly 200,000 electricity payments per month totaling $10 million in pass-through value. Cellulant in Kenya currently connects 14 banks into the M-PESA mobile money service for a total value of $70 million pass-through value per month.

While these figures sound impressive, they do not automatically translate into high profits. Aggregators require significant volumes just to break even. This is due to a few reasons:

- The business is capital intensive. Aggregators require costly inputs that range from advanced technology equipment to skilled staff. Each initial integration with a new third party costs anywhere between $15,000 to $30,000.

- Aggregators provide primarily fee-per-transaction models and only receive a portion of each fee received. Most third parties pay aggregators a small fee per transaction, similar to merchants who pay credit card processing fees. These fees, which are either a flat fee (between $0.20 and $1.00 per transaction), or a percent of each transaction value (between 0.5% and 1.5%), are further divided between the aggregator and the provider of the payment instrument (for instance, the MNO), with the aggregator receiving less than half of this share.

So far, facilitating bill payments to utilities and other companies is proving to be the most significant and reliable source of volume for aggregators. They see a lot of future potential in emerging offerings like bank account-to-mobile account integration and vice-versa; however, it remains to be seen how they will work as a revenue stream long-term.

Future of the aggregator industry

Diversification may be an important strategy for aggregators. Though they were key in building the ecosystem, aggregators are now facing intense competition from their own MNO partners in at least a few areas:

- Technical Capacity - As the mobile money ecosystem matured, MNOs upgraded their technical capabilities. Today they can more easily handle multiple direct integrations without the need for an aggregator. MNOs have also begun opening their Application Program Interfaces (APIs), enabling third parties to directly integrate their own software to MNO platforms, thus reducing the need for aggregators.

- Revenue Margins - Powered by increased technical capacity, MNOs are now looking to keep or take back the big revenue generating third party relationships for themselves, thus eliminating the need for revenue splits with aggregators.

Aggregators are responding to these threats in at least 3 ways:

- Value-Added-Services (VAS): Some aggregators are betting that VAS (receipts, reconciliations, troubleshooting, relationship managers for clients) will prove to be their unique competitive advantage – something that MNOs might struggle to replicate. Although Safaricom improved its API to integrate directly with banks, most banks still choose to connect via an aggregator, in large part due to VAS. Interestingly, some aggregators are also developing credit scoring algorithms and are trying to position themselves in the emerging market for digital credit products.

- Industry diversification: There are many business sectors, including education and entertainment, that are still figuring out how to use digital financial services to enhance their customer offerings. Chains of for-profit schools and petrol stations are some of the early targets because aggregators can often use one integration to bring many branches and thus higher volumes.

- Own critical pieces of the value chain: Aggregators who previously only provided back-end services are moving into the front-end space. They are connecting directly with customers either with their own product (e.g. Pesapal’s cross border remittance product – AfroRemit - or Selcom’s own pre-paid cards), or via their own channel (wallets, apps, agents) with the intent to build their own brand and a larger share of the value chain.

Aggregators have played a critical role in building up the DFS ecosystem so far. This will be an interesting area to watch going forward and we think at least some aggregators will adapt to their current challenges with new innovations and strategies and continue in their role of facilitating millions of DFS transactions daily.

Add new comment