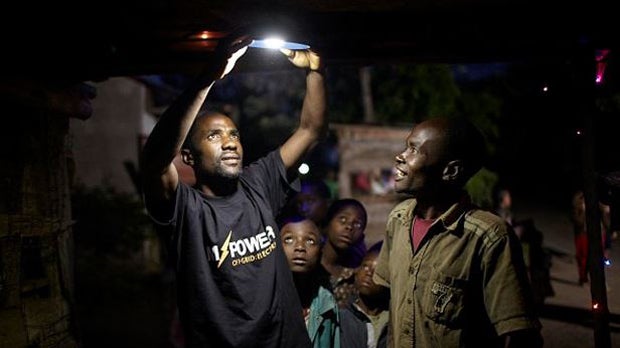

How Can Pay-as-You-Go Solar Work for Poor People?

Poor people are harder to serve. They live farther away from each other, on average. They are more risk-averse. They require more training to use new technologies. And, of course, they have little money. Providers seeking to build valuable long-term relationships with poor households need to account for these realities in their business models, and seldom is it easy.

The thing is, pay-as-you-go (PAYGo) solar companies are almost there. They have found a way to lend to medium-to-low-income households in developing markets. With an average daily cost of around $0.40, they can meet the household energy needs of many people — but not everyone. For a household earning $2 per day (the typical wage rate for a day of casual agricultural labor in East Africa), paying for the average PAYGo product would mean allocating 20 percent of income to energy, far beyond the 10 percent threshold set for “energy poverty.” For poor families, even 10 percent of income going to energy can be a strain because these families have so many unmet needs to cover. Many companies are seeking to make their products more affordable for more people — if not for the $2 per day families, then at least for a larger share of low-income majorities. As part of CGAP and FIBR research into the household impact of PAYGo solar, we looked at the costs and benefits of several tactics that providers have used to increase affordability.

Longer loans

The most common way to improve affordability is to lengthen the tenor of the loan. Going from a 12-month loan to a 36-month loan allows providers to significantly reduce the daily price of energy, making it feel affordable to a larger market segment. However, there are drawbacks to this approach for both provider and consumer. Longer loans mean much higher (and typically opaque) interest burdens for low-income households. Couple that with fewer years of ownership before the device wears out, and you may have a less attractive investment. For the provider, a longer loan creates greater exposure to repayment risks and forces them to raise more expensive liabilities to match their longer-term assets. The cost of defaults and capital must be passed on to the customer and should be factored into any loan tenor decision.

Smaller deposits

Another approach is to reduce the upfront deposit customers pay for a system. This method puts solar within reach of people who can afford the daily expense but not a $20 to $40 lump sum. This approach has its own risks. Most prospective PAYGo clients have no credit histories to check, so providers use the deposit as a screening device. If the deposit is high enough, users will start their loan with sufficient equity that they will be incentivized to continue paying. But when the deposit is set too low, that screening function is lost. In one example, reducing deposits allowed a provider to rapidly grow its customer base but caused non-performing loans to more than double.

Flexible loan terms

As we argued in an earlier post, PAYGo flexibility has been a key aspect of the model’s success. By allowing users to miss a few days of payments without shame or fear of repossession, operators can lend to people with lumpy or erratic income streams. Offering more flexibility can make solar energy more accessible to poor people, but flexibility has a cost. If a 12-month loan is priced for an average pay-off term of 13 months, then those paying on time are subsidizing their slower peers. At a much longer term, this will become unsustainable. On-time borrowers would get a cheaper price from a stricter lender.

Push basic products

One of the key barriers that we saw to the sale of basic solar home systems was the problem of rewarding the seller. Having an affordable solar home system on offer is a good step toward serving poorer customers, but providers do not see much take-up of those units if flat-rate commissions encourage their agents to sell only higher-end items. Devising incentive programs that reward sales (as well as repayments) of lower-end products is crucial to actually reaching poor households.

Successful business models that reach low-income users typically opt for a large-volume, low-margin approach. But for solar, rolling out high volumes requires large amounts of upfront capital to fund hardware and operations costs. This introduces an investment conundrum: Investors want to see profits quickly, which can force socially motivated businesses to focus paradoxically on higher-margin customers buying more expensive units in denser urban areas.

Difficult decisions

These are not simple choices, and serving this market segment may not be the right choice for every company. PAYGo solar will not reach everyone. Somewhere between 15 and 25 percent of off-grid households simply cannot afford market-based solutions and will require some level of public subsidy. But for providers and investors that do make a commitment to go down market, they must be (and often already are) intentional, unrelenting in the search for cost reductions, and uncompromising on customer service. Every effort ought to be made to keep loan tenors short, and deposits must be high enough to demonstrate effective client commitment, at least in the absence of more sophisticated underwriting.

Serving low-income customers while making a profit requires a commitment to scale and to long-term customer relationships, accepting low margins on initial offerings. It requires all of a company’s operations — from finance to agent payment structures and customer care — to reflect and align with this commitment. It’s important for companies and their backers to be clear-eyed about these costs and unified on the objectives. Reaching the poor will not happen by accident.

Comments

Good article.

Good article.

The poor familly if not spending 20% of the low income on the solar home system, it will be spent on alternative not always clean energy, and will spend more on phone charging services.

Add new comment