When is Interoperability Right for Microfinance?

Instant payment systems (IPS), the infrastructure systems enabling real-time, interoperable payments, continue to gain traction around the world. Solutions like Pix in Brazil, Raast in Pakistan and QRIS in Indonesia are changing the way users transact and expanding the horizon for what’s possible when it comes to payments.

Policymakers are increasingly looking toward these systems to help advance financial inclusion goals. Often, this means a universal vision that sees the smallest microfinance organization or savings collective connected to the largest bank. For account holding institutions, this typically means allowing customers to make payments to other providers. For non-account holding institutions (e.g., MFIs), this means enabling digital disbursement and repayment from existing stores of value.

Either way, the argument is simple: all institutions should benefit from the gains presented by real-time, digital payments. In other words, leave no institution behind. But is this the right strategy? New evidence from CGAP interviews with more than 40 small financial institutions (microfinance and rural) suggests a more complex picture.

Not surprisingly, small institutions face the biggest capacity constraints. And while they often serve the poorest and most vulnerable customers, they also typically lack the financial and technical capacity to easily join instant systems. More importantly, the strategic alignment of joining a real-time payments infrastructure can vary greatly by institution.

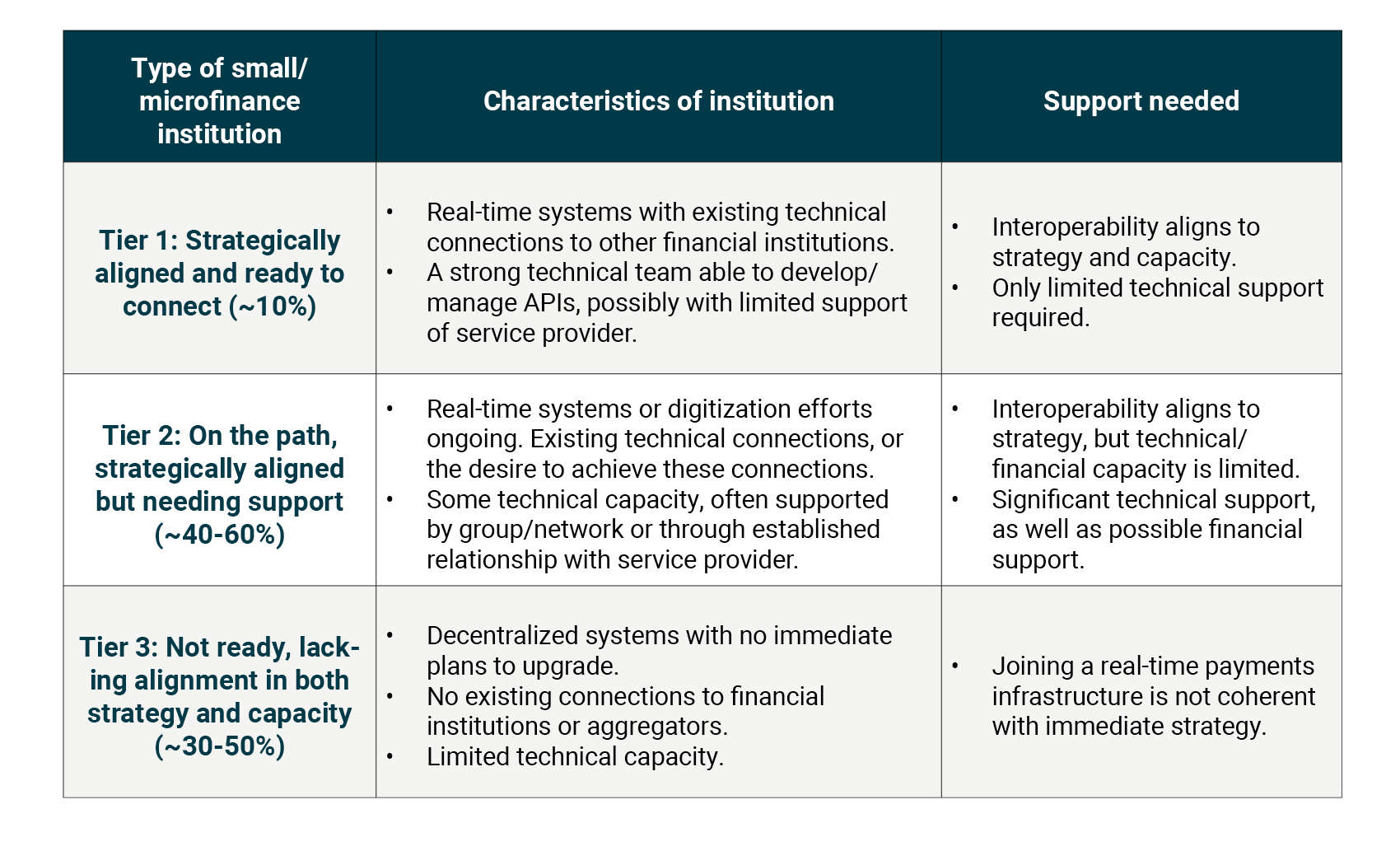

CGAP research suggests that small financial institutions typically fall into three categories related to their strategic and operational readiness for interoperability:

Tier 1: Strategically aligned and ready to connect

The microfinance bank Baobab in West Africa is one example. Each country where Baobab operates has an IT manager supported by a technology hub in Dakar. In Senegal, Baobab connects through the payments aggregator InTouch to large wallet providers such as Orange Money for disbursement and repayment of loans. Real-time interoperability fits an immediate business strategy, and the organization has the technical capacity to support integration. This is similarly true for microfinance institutions like Cantilan Bank in the Philippines and Amret in Cambodia.

However, institutions like Baobab are more the exception than the rule. This top tier often comprises 10% (or less) of the organizations within a regulatory classification of microfinance or small/rural banking.

Tier 2: On the path, strategically aligned but needing support

A larger segment (between 40-60% of small institutions), falls within a second tier. For these institutions, digital payments are a clear strategic priority, if not yet a reality. Examples include Capital Finance in Niger or Proempresa in Peru.

For such organizations, some form of digital enablement likely already exists. Capital Finance customers can follow their transactions through SMS banking, and while no digital payments are offered, a link to a wallet provider is on the horizon. The technical teams in these organizations may have experience in change management, but often with substantial support from outside actors.

For this group – strategically but not necessarily technically aligned – the extent of financial and technical support available is key. The nature and degree of support provided by payment system operators can determine whether connection is a strategic success or failure.

Tier 3: Not ready, lacking alignment in both strategy and capacity

A third group, accounting for anywhere between 30-50% of institutions, lacks both readiness and near-term strategic alignment. These organizations often have decentralized systems by branch location, may lack digital systems altogether, and, most importantly, typically do not see real-time payments as an immediate strategic enabler.

Examples of Tier 3 institutions include URCLEC in Togo or CVECA/ON in Mali. Some of these institutions may be planning to offer SMS communication with customers, but these plans are often prospective and do not extend to payments. As one might guess, this group also has the least technical capacity and most limited financial means.

Supporting small institutions for instant payments

Policymakers and infrastructure operators should ask a few simple questions when considering how to support small institutions for instant payments. First, where is each institution on its digital journey? Is interoperability a value-add for their customers in the near-term? And if so, how do their technical capabilities align to the task?

For the first tier, supporting onboarding may be as simple as clear guidance and project management support. In terms of capacity, these institutions do not look so different from many of the commercial banks or e-money issuers already in the pipeline for onboarding.

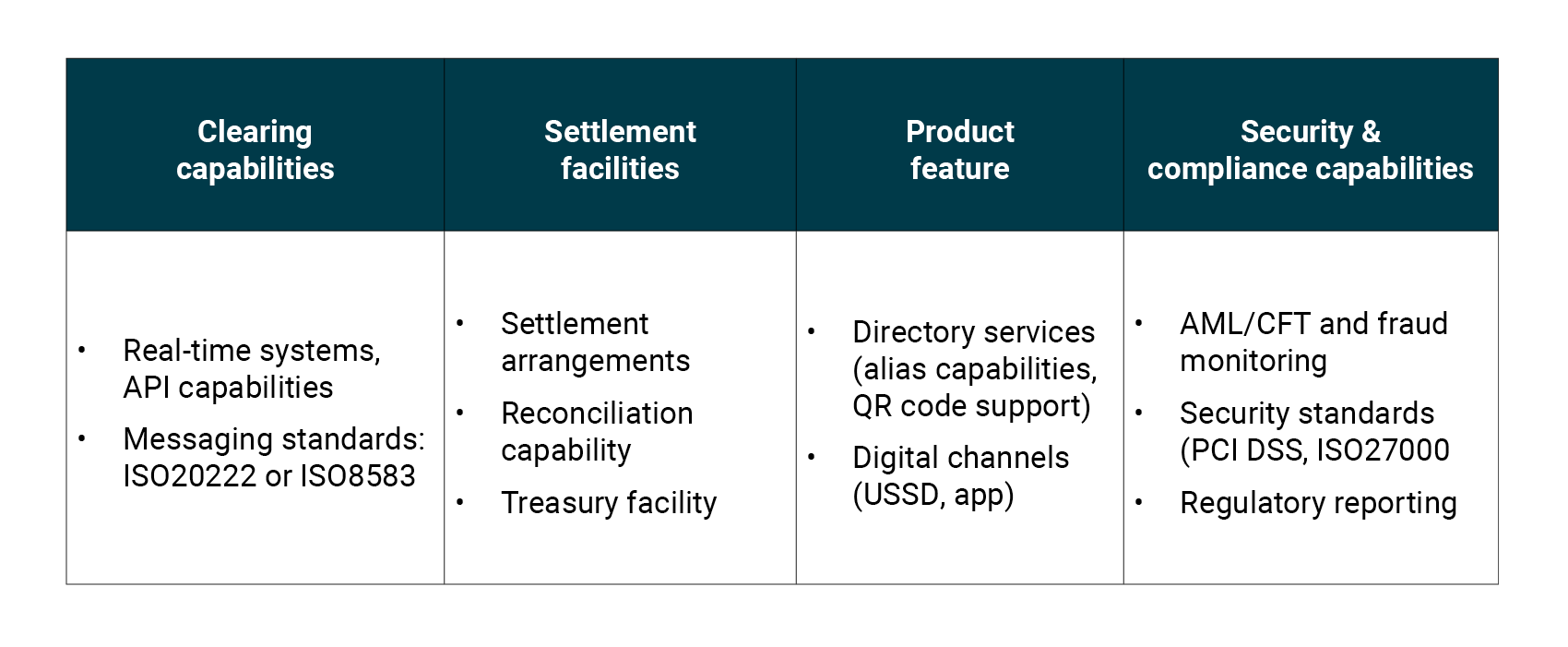

For Tier 2 institutions – those with strategic fit but limited capacity – support is critical. Participants in any instant payment system must meet a variety of regulatory, administrative and operational requirements. At minimum, this means the capability to process digital transactions in real-time. Often, it also means managing settlement facilities, upgrading security capabilities, technical expertise to support integration and administrative overhead (e.g., reporting, reconciliations).

Capacity gaps should be clearly articulated, and plans developed to help bridge these gaps. But help is often available in this task. In Tanzania, for example, UNCDF is helping to address capacity gaps for microfinance institutions by joining the new Tanzania Instant Payment System (TIPS). Africanenda, a new capacity building organization in Africa, also offers this type of support. At the system level, tools like Mojaloop are focusing on easier, more self-service APIs to help simplify onboarding.

Lastly, for Tier 3 institutions – those lacking both strategic and technical alignment – project champions may need to reassess their goals. If interoperability does not fit within the institution’s near-term strategy or operational reality, joining an IPS is likely to be more a strategic distraction than an enabler.

These three tiers may look slightly different in each country, and each institution will have its own set of competencies and constraints. More generally, the roll-out of interoperability to small institutions cannot be a one-size fits all proposition. Policymakers and infrastructure operators should consider both strategic alignment and institutional capacity.

Because in the end, the goal should not simply be to connect everyone, but rather to help each organization grow, adapt and better serve the poor.

Add new comment