Making the Case for Privacy for the Poor

Poor people in developing countries are rightfully concerned about whether their families are safe, sheltered and adequately nourished. Where does privacy fit into that mix? In many parts of the world, by constitution, statute or treaty, privacy is considered a human right. Accordingly, regardless of whether someone is rich or poor, their privacy must be protected. In addition to human rights concerns, however, there are a number of pragmatic reasons why privacy of all people should be respected, including that of poor people.

Inadequate data privacy can result in a variety of harms for anyone accessing digital financial services:

- Identity theft is one such vexing problem. Victims of identity theft spend time and money trying to reclaim their good name and account status, if even possible, after a criminal steals funds or incurs debt in their name. Scam artists also use stolen personal information to take advantage of consumers by tricking them into purchases and investments that don’t exist or are worthless.

- Financial institutions reporting erroneous information to credit bureaus can result in denials of loans, insurance and even employment opportunities. This is especially true when the individual who is the subject of the reporting either did not know the negative information was in his or her file or could not effectively dispute it.

- Some actions that violate privacy could also harm customer reputations. Some digital lenders, for example, have adopted the approach of shaming delinquent borrowers into paying delinquent amounts by disclosing these past due obligations on social media. Not only is this practice highly coercive, it could also compel customers to make payments they don’t owe.

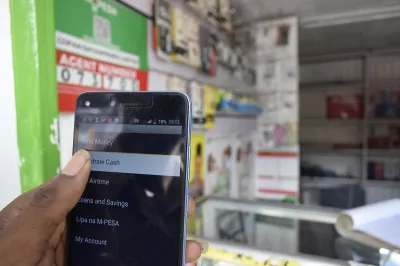

When it comes to poor customers specifically, a lack of privacy could harm broader financial inclusion efforts. Take digital credit as an example. To assess creditworthiness, digital lenders typically use data on mobile phone usage, such as how many SMS messages are sent per month, how often a SIM card is loaded, social media activity and even whether phone batteries are charged only when they are close to empty, as this could reflect on the ability to pay for electricity services. At least one lender even seeks access to the contents of SMS messages to make these determinations.

If customers fear their privacy is being violated, and that their personal information may be used in ways they are not comfortable with, then they may be less likely to use formal financial services. If they experience specific harms or losses resulting from poor data privacy and protection, then they may turn away from formal finance altogether.

Big data

With the advent of Big Data, a diverse range of information about a consumer can be accumulated, in some cases with none of the accuracy, use limitation, access and dispute protections applicable to credit bureaus. This nontraditional data can also be used in risk-predicting algorithms that sometimes result in spurious correlations that are not meaningful or accurate.

Big Data is largely made possible by the diminishing cost of storing data. It can be more expensive for companies to sort through and delete unnecessary data than to keep it indefinitely, even past the time when it is commercially valuable. It also means that lots more information can be collected at relatively little cost. This practice puts consumers at greater risk in the event of a data breach than if lenders were deleting data on a regular basis.

The new European Union data protection regulations will require that individuals’ data be portable, meaning that the data subjects will have the right to receive back the information that they provide to companies, to transmit it to other companies and to have it transmitted directly from one company to another, where technically feasible. This is an important right in the financial inclusion context because it not only empowers consumers to control their own information, but also enhances competition – it allows consumers to move their transaction history to a new provider.

The way forward

In this context, how should privacy for the poor be addressed? In keeping with CGAP’s evidence-driven approach, a key first step is getting feedback from consumers about their personal preferences regarding privacy. To what extent does extensive information collection trouble them – or not? Do they care who sees their data (providers, government or neighbors)? Initial answers to these questions will be addressed in the next blog in this series, and CGAP will undertake new research in the coming months to build the evidence on consumer attitudes and behaviors.

Another important step in addressing privacy is to bring together stakeholders – including providers, regulators, policy makers and investors – to discuss solutions. What personal information is needed to offer products and to be profitable while still providing privacy protections? How can consumer trust regarding use of their personal information be established and preserved? What information should be permissible to use for data mining and cross-marketing? How beneficial are marketing uses of this information for the poor? How can consumers be made aware of secondary uses of their information and perhaps be given the opportunity to opt-out or opt-in to such uses?

Businesses could take steps to educate the poor about how their personal sensitive information will be treated, providing choices regarding information usage and, where appropriate, committing not to collect more information than is needed. Self-motivated companies could undertake these commitments through industry-driven self-regulatory agreements or codes of conduct, or though the imposition of legal requirements.

Regardless, transparency and restraint regarding information collection could benefit both consumers and those offering financial services, thus increasing consumer privacy, decreasing the risk associated with data breaches and expanding consumers’ use of new financial products and services.

Add new comment