Debt Relief in the Pandemic: Lessons from India, Peru, and Uganda

COVID-19 BRIEFING: Insights for Inclusive Finance

|

The widespread use of debt moratoria in response to the COVID-19 health and economic emergencies has succeeded in stabilizing financial systems and given borrowers all over the world immediate, if temporary, relief. Financial regulators in at least 115 countries in March and April 2020 issued special permission for financial services providers (FSPs) to provide moratoria and other debt restructuring, unleashing an extraordinary effort to reprocess millions and millions of loans. In many countries, this restructuring involved major portions of their loan portfolios, and in some countries, efforts focused on loans to small enterprises and low-income borrowers. As poverty rates and food insecurity rose worldwide, the moratoria have helped millions of people, especially the more vulnerable, better manage their shrinking resources. This Briefing examines how the debt moratoria unfolded in three countries - India, Peru and Uganda - to better understand the impact on consumers, especially low-income borrowers, and the tradeoffs regulators and FSPs made between achieving financial stability and meeting consumers’ needs. It builds on CGAP’s preliminary assessment of risks to borrowers to provide recommendations for regulators and FSPs on managing credit in emergencies in a way that gives consideration to balancing the needs of low-income and vulnerable customers (Rhyne, Elisabeth 2020). |

I. Introduction

From a financial stability perspective, the debt moratoria in India, Peru and Uganda represent a successful application of the financial system’s in-built ability to absorb shocks. Financial regulators achieved their two main goals of preventing FSP balance sheets from deteriorating and bringing short term debt relief to millions of borrowers. It is a credit to policy makers and FSPs that they accomplished this massive undertaking so quickly within the first weeks and months of the pandemic.

From the perspective of borrowers, the story is somewhat mixed. Several aspects of design and implementation of moratoria influenced whether borrowers benefitted. For example, the design of most moratoria meant that the additional financial costs of accrued interest were passed to customers. In India, a question arose regarding who should bear this extra cost. Another key issue, particularly in Peru, involved the tradeoff between consumers’ right to choose whether to accept a moratorium and the need for fast, system-wide action to ensure stability. At the FSP level, implementation challenges included the urgency for effective customer communications at a time when face-to-face contact was prohibited – particularly for vulnerable and remote segments. FSPs and regulators had to make extra efforts to ensure that customers understood their choices well. Lessons were also learned about the agility needed to adapt as an emergency unfolds.

The lessons we draw from policy makers involve giving greater weight to the needs of consumers: they need to be well-informed, to have choices, to be protected from the risks that arise during a time of uncertainty, and finally, to be heard and understood. This requires regulators and supervisors to actively monitor the market in real time. For FSPs, we recommend preparing for future disruptions through digital transformation in three areas: client communications, digital transactions, and internal IT systems.

This Briefing is based on interviews with key stakeholders and review of publicly available survey data, regulations, FSP materials and press accounts. It begins with a brief account of the severity of the pandemic in each country and its impact on economies and vulnerable people. The next section explains how regulators framed moratoria policies and how this framing affected customers. The paper then turns to how FSPs implemented the policies and how consumers responded. The fourth section draws lessons for regulators and FSPs on topics ranging from hastening digital transformation to emergency preparedness.

II. The Pandemic and Its Economic Disruption in India, Peru And Uganda

Despite differences in severity of the pandemic, preventive measures delivered serious shocks to all three economies. Peru and India experienced severe epidemics, while the incidence of the COVID-19 virus in Uganda was far lower. Peru at one point had the world’s highest per capita deaths from COVID-19, and India had the world’s second most cases, while Uganda counted fewer than 1,000 deaths by November 2020 (New York Times 2020). Nevertheless, the lockdowns were broadly similar in each country, and all followed roughly similar timetables: restrictions starting in mid-March, and most businesses reopening with safety precautions in place between May and July, though Peru’s reopening was somewhat slower.

Economic restrictions quickly pushed low-resilience people into hardship. Globally, millions of people have become poorer in 2020, including an estimated 88 to 115 million people moving into extreme poverty (World Bank 2020c). In the three countries studied, most families experienced a decline in their financial situation during April and May. In India, about half of lower income people said their family financial situation was much worse, with 81 percent experiencing a decline (60_decibels). In Peru, 30 percent reported being food insecure with another 47 percent somewhat insecure (Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, quoted in Zegarra). In Uganda, 40 percent reported no income, and another 47 percent reported reduced income (Finmark Trust). Starting in July, the situation began to stabilize, and some people returned to work.

Specific segments were more vulnerable. In all three countries, women were more vulnerable than men. For example, in May, Finmark Trust found 28 percent of women saying they were unable to pay for living expenses, while under 5 percent of men said the same. Immigrants and internal migrants faced special hardships, including those in Uganda’s large refugee camps, and Peru’s over one million Venezuelan immigrants. In India and Peru, the lockdown prompted internal reverse migration: daily laborers returned to their rural homes when urban work disappeared. People in sectors especially disrupted by the lockdown were also hard hit, such as urban small businesses, market traders, restaurants and transport operators, and teachers whose schools remained closed. Those dependent on remittances, such as older rural residents, were also affected.

Managing debt became a challenge. With widespread income losses threatening borrower ability to repay, FSPs and their customers focused on debt management rather than new credit. In India, 57 percent of respondents said their payment and repayment obligations were a burden, as did 53 percent of respondents in Uganda. A substantial share of these said they had stopped or slowed repayments (60_decibels 2020). In Peru, 61 percent of survey respondents said they had stopped utility payments and 34 percent had stopped paying rent (Instituto de Estudios Peruano 2020).

In this setting, few people sought formal financial institution loans. In Peru, a May survey by the Instituto de Estudios Peruanos found that only 8 percent of respondents reported that borrowing from a financial institution was one of their coping mechanisms. A minority of people borrowed, and of those who did, few used FSPs. A study by 60_decibels between April and November found two thirds of those who borrowed in India and Uganda borrowed from family and friends, while less than 20 percent borrowed from financial institutions. Small loans from digital lenders were a relevant source in Uganda, with 23 percent of 60_decibel’s borrowing respondents citing that source. To underline the point, FINCA Uganda recorded fewer than 100 loan requests in April.

III. Consequences of Regulatory Decisions on Borrowers

In each country, regulators had to make choices on the design of moratoria. Regulators quickly recognized that the lockdowns would have a serious effect on the liquidity and possibly the solvency of financial institutions. As in many countries across the world, in March and April regulators in these three countries issued special guidance allowing FSPs to grant moratoria and restructuring without recording paused loans as higher risk and without detriment to borrower credit scores. FSPs did not have to provision for rescheduled loans, which protected their capital adequacy, at least on paper. Moratoria were among multiple regulatory measures to protect the financial system and its customers, from easing reserve requirements to supporting borrowers through government-funded loan programs.

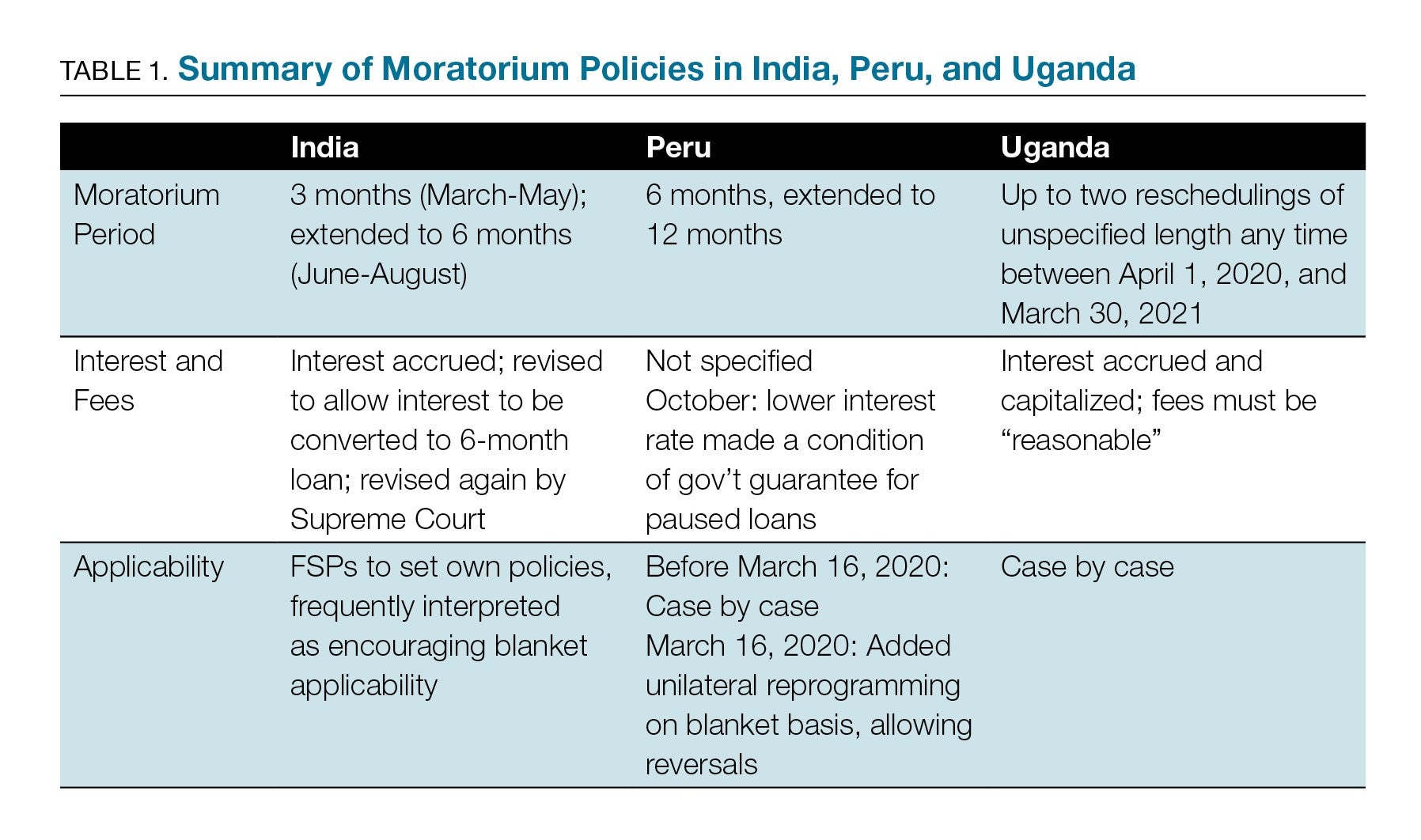

In establishing policies for moratoria, regulators confronted key choices: how long would the moratoria last, how would eligibility be determined, and how would the costs (both interest and administrative costs) be allocated? Each country selected a different approach.

Uganda: Uganda’s approach, which granted wide discretion to FSPs, was perhaps most typical of other countries. The Bank of Uganda (BOU) gave FSPs the discretion to offer moratoria or restructuring on a case-by-case business anytime between April 1, 2020 and March 30, 2021, with up to two reschedulings on any loan. It allowed interest accrual, including interest capitalization (that is interest conversion into principal or interest-oninterest). Fees were to be “reasonable”. At first, only loans in good standing were eligible, but BOU later permitted moratoria even for loans with some arrears.

Peru: Peru mounted a broader, more immediate response. While granting FSPs the ability to offer case-by-case reprogramming, the Superintendence of Banking, Insurance and Private Pension Funds (SBS) also allowed them to unilaterally reprogram entire portfolios nationwide, and many FSPs followed this option. FSPs were allowed to give all loans in good standing moratoria of up to six months (later extended to 12 months, and to include loans up to 30 days late). For unilaterally reprogrammed loans, SBS required FSPs to notify borrowers, but not necessarily until the lockdown was over. Borrowers who wanted to keep the original conditions had to contact their FSP. SBS guidance was silent on interest and fees. In October, 2020, in recognizing that the economic impact of the pandemic had continued for many months, the government of Peru issued a loan guarantee program for paused loans, conditional on the FSP reducing the existing interest rate.

India: The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) issued a directive permitting FSPs to grant three month moratoria on term loans through May 31, 2020 later revised to the end of August, such that the moratoria period in India was fixed across the entire system (Reserve Bank of India 2020a). RBI later allowed accrued interest to be capitalized as a “funded interest term loan” payable over the following six months. Although the provisions gave FSPs discretion, the industry interpreted the guidance as encouraging blanket use of moratoria.

|

Burden Sharing in India: The Interest-on-Interest Conversation In India, the Supreme Court was asked to consider who should bear extra interest charges arising from moratoria. At the time of the request, practices varied widely. Some FSPs simply deferred payments, some charged simple interest, and some also charged interest-on-interest (converting interest to principal and allowing it to compound). A suit before the Court argued that interest-on-interest was unfair and a hardship during the pandemic. The court directed the question to the Ministry of Finance, which took the position that charging a fee for non-repayment of interest is core to how finance works and changing this would be unfair to timely repayers. The court accepted this argument. However, it directed the government to give borrowers relief. This contentious issue was ultimately resolved when government agreed to use its own funds to finance the difference between simple and compound interest for loans in moratorium smaller than roughly US$275,000. Customers pay simple accrued interest, while FSPs receive a refund representing the difference between what customers pay and the full intereston- interest. This case affirmed that, as a core principle of finance, FSPs may charge compound interest. It placed the burden of extra pandemic costs on neither on FSPs nor on small borrowers, but on government. Sources: Rajapa, Battacharya et al. and Venkatesan |

Most moratoria policies increased total costs for borrowers through interest accrual (and sometimes fees). Interest accrual with capitalization fully compensates FSPs financially over the course of the loan, and fees compensate them for additional reprogramming costs. Borrowers end up paying more interest, more principal and waiting longer until a loan is fully repaid and a new loan can be accessed. In Uganda and India policies allowed for accrual of interest during the moratorium period. They also authorized interest capitalization, resulting in “interest-on-interest” during the remaining period of the loan, which became a matter of contention in India (see text box). BOU allowed “reasonable” reprogramming fees. Peru’s SBS at first was silent on interest rates and fees, in line with its longstanding policy against involvement in pricing, until it offered a loan guarantee program for loans in moratoria in October 2020.

For borrowers, additional interest costs are highest for loans near the start of their amortization periods, for short term loans, and for high interest loans. It is likely that many borrowers did not fully understand these implications when agreeing to moratoria.

Communication from regulators with FSPs and borrowers was challenging. Although regulators placed the major burden of communicating with customers on FSPs, as discussed in the next section, they recognized their own responsibility to ensure that everyone would hear about the opportunity of receiving a moratorium. They also quickly realized a need to reduce confusion about terms. Regulators in India and Uganda communicated through mass media and in some cases social media. In India, a large share of respondents in a survey by the microfinance association MFN reported that they were well aware of the moratoria offer, based on large scale outreach efforts by government, local leaders, and community organizations. General awareness, however, was insufficient to convey detailed understanding. In Peru, SBS carried out more limited communications, and this may have contributed to consumer complaints about blanket moratoria.

A key challenge for consumers was the right to choose. In Peru the unilateral blanket approach protected FSP solvency and financial system stability immediately but raised the issue of consumers’ right to choose whether to participate in the debt relief. Customers who preferred to keep paying – either because their income had not dropped or because they wished to avoid additional costs associated with moratoria – faced a fait accompli that was difficult to reverse. At the end of the state of emergency in July 2020, SBS modified its market conduct regulations, requiring FSPs to inform customers on how to reverse the reprogramming of their loans if they did not agree to the unilateral proposal, and, if needed, to offer a restructuring with alternatives based on the customer’s needs. In Uganda, from the start, the guidelines called for borrowers to consent to restructuring and FSPs to keep proof of consent. Indian regulations did not address this question, but many FSPs decided to issue blanket moratoria, generally with an opportunity for customers to opt out. At Ujjivan, a small finance bank, 18 percent of borrowers preferred to keep paying, while at Annapurna, a large nonbank microfinance institution, only 69 percent said that the moratoria benefitted them (Rhyne, Elisabeth 2020).

Despite intent to protect borrower standing in credit bureaus, results are unclear. As the pandemic began, authorities in all three countries directed that placing a loan into moratorium should not damage a borrower’s credit report or credit score.

- In Peru, FSPs were required to continue providing detailed reports on all outstanding loans, identifying loans that had been reprogrammed. Although such identification was not to damage credit reports or credit scores, a number of complaints arose about credit scoring during the early months of the pandemic.

- Similarly, in Uganda, the BOU initially suspended reporting for loans in moratorium but later directed banks to report paused loans with a special template.

- In India, RBI directives were similar, but the response differed. In interviews, lenders said they stopped reporting to credit bureaus. The credit bureaus suspended customer data until the end of the moratorium period, whether a person was paying or not, creating a hiatus in credit information from March to August.

After the moratoria, credit records will be harder to interpret. Many reports will have gaps, while others will have special designations showing reprogramming. New lenders will see these special designations, even as they are told to ignore them, with uncertain consequences for credit approvals. It is also likely that many inaccuracies will occur, due to the volume of irregular loans and limitations of reporting system.

Portfolio quality became opaque. Once FSPs began implementing moratoria widely, standard portfolio quality indicators were no longer reliable, neither for individual FSPs nor at the system level. Regulators and FSP managers became unable to monitor the soundness of the portfolio for the obvious reason that with repayments not expected, no information flowed in about borrower willingness and ability to repay. Due to limitations in IT systems and confusion over guidance, it is also possible that FSPs may not have reported uniformly to regulators on portfolios in moratoria, making national aggregates difficult to interpret.

IV. FSP Implementation Challenges Had Consequences for Borrowers

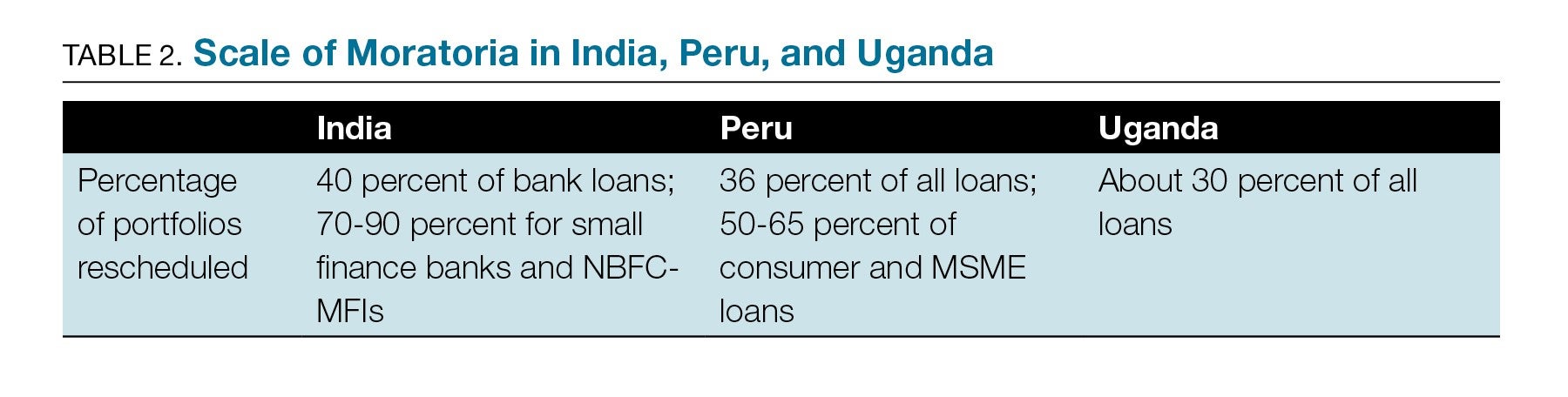

FSPs applied moratoria to the loans of many millions of clients. Across the world, FSPs put major shares of their loan portfolios on hold in an effort of unprecedented scale. In the three countries studied, one third or more of all loans were put into moratoria, with a much higher percentages for small loans. For example, in the case of Indian NBFC-MFIs, as many as 90 percent of the loans were paused. Moratoria use was slightly lower in Uganda, possibly because blanket moratoria were not provided. The typical length of moratoria in Uganda, three to four months, was also shorter than in India, where it was six months, and in Peru up to 12 months).

Managing an operation of this scale, especially during a lockdown, involved major implementation challenges. FSPs devoted staff and technology resources to processing the changes, even as they were also managing other pandemic-related problems, including maintaining basic operations and preserving their liquidity.

The pandemic created urgency to communicate with clients while simultaneously blocking communications and transactions. During the strict lockdown periods, transport restrictions curtailed face-to-face interactions with borrowers. This was especially problematic for the many microfinance institutions relying almost exclusively on face-to-face client contact. In Uganda, although FSPs were deemed essential, staff who rely on local boda bodas (motorcycle taxis), were unable to reach their workplaces or visit clients. In both India and Uganda, restrictions disallowed group meetings.

The first effect of these restrictions was reduced FSP ability to collect loan repayments. According to Sa-Dhan, an Indian microfinance association, repayments among their members were below 12 percent in May. The second effect of transport restrictions was difficulty in informing clients about moratoria and negotiating moratoria with them.

FSPs turned to digital means and mass media, but this disadvantaged vulnerable customers. In Uganda, FSPs used radio for mass announcements and SMS for individual communications. However, 44 percent of Ugandans, including the majority of the poor, do not have a mobile phone or SIM card (Financial Sector Deepening Uganda 2020), and even with a phone, many lacked airtime. Similarly, in Peru, FSPs discovered difficulties in contacting clients by phone, as many had changed phone numbers or lacked airtime, and in rural areas mobile coverage was often spotty.

In Uganda, BRAC Microfinance Bank purchased airtime for customers so that its staff could talk with or text them. Some MFIs in Peru decided to break operational protocols and contact clients by phoning neighbors, friends or relatives. FSPs also put forth steady streams of announcements on social media, but such channels were not the best way of reaching lower income borrowers. In a typical example, Facebook posts by Finance Trust Uganda had at most a few hundred hits. FINCA Uganda held webinars to inform clients, though it is not clear how many clients they reached this way.

Importantly, even though SMS and phones proved to be the best ways to reach customers, they, too, were restricted, because many FSP call centers were closed or thinly staffed. Staff could not reach call centers and were not equipped to work from home.

|

Regulators in Peru Created New Ways to Hear Consumer Complaints During lockdown, SBS and the consumer protection agency INDECOPIa found new ways to interact with customers. SBS strengthened its call centers, website and capacity to manage the large volume of queries and complaints. INDECOPI also deployed a range of means to reach people, using websites (“Reclama Virtual”), WhatsApp numbers, e-mail addresses, and hotlines to receive complaints. It launched the “citizen report”, an online platform that enables citizens to express concerns and complaints, which has provided crucial real-time information to INDECOPI and other agencies. It received 21,116 reports against FSPs, including 2,143 related to credit reprogramming, according to its press release. Source: Moreno Sancheza Instituto Nacional de Defensa de la Competencia y de la Protección de la Propriedad Intelecual |

Moratoria terms were hard to explain and understand, opening the way for mistakes and abuses. FSP staff and borrowers had to learn new terminology and parse the complicated arithmetic of interest accrual. FSPs did not always use terms precisely or in the same ways, especially in local languages. These difficulties increased the chances of poor customer decisions and calculation mistakes.

Despite directives mandating full disclosure and the production of educational material, customer complaints about lack of understanding show that communications did not go far enough. Client complaints rose in India and Peru. In a customer survey by the Microfinance Institution Network (MFIN), an Indian microfinance association, a quarter of respondents said they did not fully understand the choices confronting them regarding costs and loan terms.

Implementing moratoria raised several consumer protection risks, some of which were mitigated. There is global evidence that consumer risks increased during the pandemic (Medine 2020). At least three factors contributed to an environment conducive to frauds, unfair treatment and lack of transparency: pressure on FSPs (internally and from funders) to restart their operations, customer need for fast cash, and confusion throughout the sector. In the three countries reviewed, regulators and industry associations took measures to improve customer protection.

In India, many FSPs encouraged borrowers to make partial payments, which in itself is not a problem. However, the fact that such collections did not follow the automatically-generated schedules that normally track payments due created a window for employee fraud. Staff could record a smaller repayment than received and pocket the difference. Some FSPs that identified this loophole instituted follow-up verification calls to borrowers.

|

Self-Regulatory Organizations in India Helped Make the Moratoria Process More Orderly and Safer for Borrowers “The concept of moratorium was new to MFIs, and the arithmetic of it was unclear. So we had to work with the sector as a whole to decide different ways in which it could be implemented” -MFIN Throughout the pandemic, the two leading Indian Microfinance industry associations, Sa-Dhan and the Microfinance Institution Network (MFIN), in their designated roles as Self-Regulatory Organizations (SROs), have helped microfinance lenders to interpret regulatory guidance, plan their operations, communicate with customers, and forestall potential customer risks. Both SROs operate helplines for receiving customer queries and complaints. After RBI gave its broad policy statements, MFIN issued more specific guidance about moratorium terms and the rights of customers. At the same time, MFIN surveyed consumers and shared results with FSPs. Findings were used to develop training for FSP staff and improve messaging across the sector. Surveys also provided early warnings about consumer problems such as loan officer misconduct. Source: Venkatesan and MFIN |

People in need of quick cash turned to less-regulated lenders, including digital apps (India and Uganda) and informal moneylenders (Peru). In India and Uganda, digital lenders have proliferated in recent years, and most are not regulated. Evidence surfaced on Indian social media that digital lenders were not providing moratoria and may have used coercive collections practices. The Twitter hashtags #saveourcontactlist and #OperationHaftaVasooli featured examples in which digital lenders sent messages to borrowers’ phone contacts, harassing them with unwanted calls, shaming borrowers, or threatening legal action. Given the unregulated nature of most digital lenders, customers have limited means of recourse. However, a digital lender trade association is working to establish norms, and the RBI has attempted to ensure that there is some oversight of these lenders through instructions to the regulated FSPs – banks and nonbank finance companies – that partner with them (Reserve Bank of India 2020a).

Confusion about the cost of moratoria also raised disclosure and transparency issues, which were reflected in complaints. Complaints about lack of clarity in messages arose in India and Peru, including a few complaints that FSPs were deliberately obscuring the cost implications. In a customer survey by MFIN, a quarter of respondents were concerned that they did not fully understand their choices. In Peru, complaints addressed not being informed about unilateral reprogramming and credit scoring issues, among other topics.

Limited FSP capacity to process the large number of reprogrammings shaped the offer and customer experience of moratoria. Blanket moratoria were a fast alternative to case-by-case reprogramming, but they did not suit everyone. In ordinary circumstances, negotiating a moratoria involves several steps: the borrower asks for relief, the lender offers terms, the borrower accepts, and the loan documents are revised and signed. Such a step-by-step process was used in Uganda for all moratoria, and in India for loans to middle-income segments. It was an unprecedented, staff-intensive process. FINCA Uganda pulled in staff from every department of the organization for an all-hands-on-deck, weeks-long effort. Recognizing the challenge, BOU informally signaled to FSPs that they could approve moratoria through phone calls, with formalities later. The workload associated with case-by case processing basis may have led to delays and possibly to lower uptake.

Recognizing this heavy workload, the regulator in Peru and some FSPs in India opted for blanket moratoria covering all loans at once, or all loans of one type. In India, many FSPs, especially in the microfinance sector, recognized the limits of their IT systems and staff in processing case-by-case reprogramming. For the group lenders prevented by lockdowns from receiving cash repayments in the field, blanket moratoria simply formalized reality.

The need for digital upgrading was highlighted. Many FSPs in India with older IT systems had to process revisions manually, and some systems were simply unable to cope with so many loans with unconventional schedules. FSPs in Peru reported that their customer relationship management (CRM) systems were not good enough at retrieving up-to-date customer information. Peruvian FSPs had to reprogram their systems several times as guidance changed. A number of FSPs, such as Mibanco and Caja Arequipa in Peru and Centenary Bank Uganda, had previously introduced app-based services for transactions, but customers had not taken them up widely. During the pandemic, FSPs relentlessly promoted their digital services, sensing an opportunity to change customer behavior. Overall, the pandemic brought out the need for FSPs to invest in digitization at all levels: CRM systems, call center technology, digital apps, and other means of communicating and transacting remotely.

V. Lessons on Moratoria and Emergency Preparation

In our previous Briefing on borrower risks, we proposed preliminary recommendations for managing credit during the pandemic. Now, with insights from India, Peru, and Uganda, we can refine those recommendations for regulators and for FSPs.

LESSONS FOR REGULATORS

Debt moratoria were an effective way to provide quick and necessary relief to FSPs and borrowers. The quick decisions of policymakers to encourage moratoria and rescheduling may well have averted much greater cost and instability that would have come if FSPs had failed. For borrowers, too, credit relief may have helped families meet basic needs during the time of greatest stress. Moratoria made good use of the shock-absorbing capabilities built into the financial system.

Regulators must consider how to allocate the cost burden imposed by a crisis. In all three countries, regulators put the burden on customers to pay the extra financial costs through accrued and compound interest, and in some cases fees. These decisions reflected concern for FSP viability and financial system stability. However, a counterargument can be made for burden-sharing in a general emergency such as the pandemic, with special consideration given for the more vulnerable. Under that argument, borrowers would be offered as much relief as possible, consistent with FSP survival. In India, the Supreme Court ultimately required government to carry the extra burden of compound interest, taking it off the shoulders of both FSPs and borrowers.

Consumers should always have the right to accept or reject a change in the terms of their loans, even if the change is being made for their benefit. Because moratoria impose a long run cost on borrowers, borrowers who can continue to repay are better off doing so. The response of consumers in Peru to unilateral reprogramming demonstrated that borrowers are sensitive to their right to choose.

Regulators have a duty to communicate with consumers. While regulators placed most of the burden for communicating with customers on FSPs, they also found that, as a matter of forestalling consumer risks, they needed to communicate directly through mass media. Communications were intended to ensure that the public heard about the possibility of moratoria and especially to ensure that the messages the public received accurately reflected official policy. Some financial system authorities also provided scripts and messages for FSPs to use. In a time of potential confusion, regulators may need to ensure uniformity in the messages they and the FSPs send to the public.

Agile and consultative regulation is essential as a crisis evolves. Regulators in all three countries responded to the pandemic with admirable speed, possibly forestalling deeper problems. Initial responses were based on past experience and forecasts about the pandemic. However, these responses had to be revised repeatedly, both because the pandemic lasted longer than initially expected and to respond as implementation challenges emerged. Agility requires policy makers to monitor both FSPs and customers to glean information needed for fine-tuning. BOU held weekly meetings with its FSPs throughout the pandemic, which allowed it to provide informal guidance. MFIN in India monitored complaints. SBS and INDECOPI in Peru met often with FSPs and developed new tools to monitor consumer complaints.

Regulators and supervisors can monitor the market in real time. There is a growing recognition of the need for pro-actively using a range of tools to monitor consumer risks. Given the particular stress put on borrowers during the pandemic, regulators and supervisors needed real time information. There are several ways for regulators to monitor the market and better listen to the collective voice of consumers, for example through consumer associations, regulatory consumer councils, and use of supervisory technology and social media (Griffin and Duflos). It is also important to publish information from customer complaints so that other customers can make appropriate decisions.

Greater scrutiny is needed on digital lenders. Observers believed that many customers were turning to digital lenders to meet immediate cash needs, especially when mainstream FSPs stopped operating. However, because these lenders are not always directly regulated, it was not possible to determine whether digital lenders were offering relief such as moratoria or on what terms. In India, social media revealed complaints about collection pressure from digital lenders. This experience made it clear that policy makers need to be able to see the scale and scope of digital lenders’ activities. Market monitoring tools, such as the ones developed by CGAP to monitor digital credit in Kenya and Tanzania and mystery shopping, could be considered (Kafenberger and Sobol 2017).

LESSONS FOR FINANCIAL SERVICE PROVIDERS

FSPS need to communicate proactively with consumers. Before an emergency, FSPs should develop and test multiple channels for contacting customers, with special attention to reaching the most remote and vulnerable. Technology-based channels proved to be particularly important, as did keeping contact information up to date. During an emergency, messages must be clear, consistent, and easy-to-understand. In this pandemic, borrowers needed extra help to understand the moratoria.

FSPs can take the opportunity to accelerate digital transformation. If there is a silver lining for FSPs in the pandemic, it may be that it will accelerate their installation or upgrading of digital means to communicate and transact with their clients and their internal systems. Many FSPs in Uganda moved quickly to install digital systems, and some FSPs reported that necessity drove them to change much faster than they believed possible. FSPs in Peru noted that previously digital-shy customers used digital channels for the first time. Inside FSPs, difficulties processing moratoria revealed the need to upgrade IT systems to cope with irregular loan schedules and to maintain more current CRM systems.

FSPs need to update their emergency protocols. Many FSPs were caught flat-footed because their business continuity scenarios did not cover the situations brought on by the lockdowns. Staff could not reach offices and were not set up to work from home. FSPs can incorporate the strategies developed during the pandemic into current operations and future emergency protocols.

Seek clarity around credit bureau treatment. Given the confusion that emerged around credit bureaus in receiving, recording, and reporting moratoria, it would be useful to conduct post-pandemic investigation to determine whether borrowers’ standings were effectively protected. In India, where credit bureau reporting all but stopped for several months, a more thorough reckoning of the role of credit bureaus may be needed.

VI. Concluding Note

We cannot yet say how the story will turn out for borrowers and for FSP portfolios in the long term. Many loans have completed their moratoria periods, while other moratoria are still in effect, and it will be some months before complete data on loan repayment is available. Given the uniqueness of the moratoria experience, it will be important to examine that data a few months from now, to draw a full picture of its impact on borrowers.

Moratoria involved regulators, FSPs and consumers in important tradeoffs, most notably between the immediate needs of FSPs and the financial system and the needs of customers for clear and beneficial choices. Going forward, it would be useful for regulators to better understand how the moratoria affected customers so that they can uphold the needs of consumers when making emergency decisions in the future. FSPs and regulators, both separately and together, should set aside time to analyze the lessons from the moratoria experience and incorporate them into their emergency protocols.

To view full list of references, please see PDF.

|

The authors of this Briefing are Elisabeth Rhyne and Eric Duflos. Jayshree Venkatesan, and María Moreno Sanchez provided significant research. We thank Gerhard Coetzee and Juan Carlos Izaguirre for their input, and Stella Dawson and Esther Lee Rosen for their editorial support. |