Complaints data are often the first type of data a market conduct supervisor (MCS) uses to build up its market monitoring function. An MCS usually starts with analysis of aggregated complaints data obtained from reports financial services providers (FSPs) are required to submit on the number, nature, severity, and resolution of complaints received. The MCS may also gather information from other teams within its authority, other regulators, consumer associations, and ombudspersons that handle consumer complaints or disputes.

Not necessarily. Consumers more likely are reluctant to make complaints because they do not trust the system to help or do not have the knowledge or resources to do so. When consumers rarely complain, an MCS can monitor FSP conduct through other means, such as thematic reviews and consumer surveys. These types of solutions build consumer confidence and understanding of complaints processes through public awareness and education campaigns, as do enhanced disclosure of complaints processes by FSPs.

Although complaints data are anecdotal and not statistically representative, their analysis can be a starting point to help the MCS identify consumer risks, prioritize work, and take supervisory action. For example, the MCS may use complaints trends to schedule thematic reviews; refine the scope or timing of scheduled examinations; provide input into risk assessment matrixes and reports; and flag problems that may require consumer warnings, financial education efforts, or regulatory changes. Some MCSs publish anonymized complaints data and trends in official reports or on their websites, which adds transparency and a deterrent effect by shining a light on problematic products and FSPs. Regulators, policy makers, consumer advocates, researchers, law enforcement, and members of the public may also use market-level complaints data for various analyses.

For the purposes of this toolkit, we define “complaints” as expressions of dissatisfaction by (or on behalf of) customers that are related to their experiences with FSPs. Complaints may relate to the quality of a product or service, treatment by an FSP (including its agents and other third parties), or suspected wrongdoing. Complaints are different from general inquiries (e.g., where can I find an ATM?) or legal disputes between parties that may require formal dispute resolution.

This tool describes how MCSs focused on protecting financial consumers can analyze data from consumer complaints and use it as an effective market monitoring tool. The tool only relates to the use of complaints data for market monitoring purposes.

Benefits and opportunities >

Characteristics of this tool >

How to use this tool >

Limitations of this tool >

Other resources >

Benefits and opportunities

Incorporating complaints data into market monitoring activities offers a number of benefits:

- Responsiveness. It allows an MCS to identify and more quickly respond to increasing risks— depending on consumers’ propensity to complain, recorded categories of complaints, and timeliness of access to complaints data.

- Segmentation. It enables an MCS to identify the different risks and problems various consumer groups face, especially vulnerable segments (e.g., gender-based discriminatory treatment during the complaints handling process), by segmenting complaints according to gender, location, age, income, and other consumer characteristics.

- Supervisory effectiveness. It helps an MCS prioritize supervisory programs and resources based on assessed risk, for example, segmenting complaints data by product and provider type to identify

- The most common problems consumers face

- Serious issues that require immediate supervisory action

- Types of complaints that take longer to resolve or persist over time

- Geographic concentrations or seasonal influences

- Variations by gender or by vulnerable group(s)

- Variations by access or communication channel

- Subsectors (e.g., digital lenders) that produce disproportionately higher levels of complaints or a growth in complaints over time (compared to size or number of accounts

- Issues with new licensees or issues resulting from intense competition in the sector

- FSPs that are slower than average to resolve complaints or have high rejection rates

- Gender differences in resolution time or percentage resolved in favor of the customer

- Dissemination. It helps an MCS to push for better FSP practices by periodically circulating main aggregated complaints indicators that provide additional resources for consumers, consumer groups, and the media.

Systematically automating the collection and analysis of complaints data (e.g., through new suptech techniques based on supervisory needs) can also improve data quality and the overall efficiency of an MCS department and its functions.

Back to top ↑

Characteristics of this tool

Complaints analysis can draw from numerous sources, including regulatory reports submitted by FSPs, complaints MCSs have directly received, and information shared by dispute resolution mechanisms or other sources. A good place to start is data obtained from regulatory reports.

Aggregate complaints data from regulatory reports

Aggregate complaints data submitted by FSPs is often one of the first types of market monitoring inputs an MCS uses. These data are helpful in highlighting potential conduct or operational issues at FSPs, including issues related to complaints handling. To ensure the data are comparable across institutions and provide an accurate market-level perspective, it is beneficial to establish a common framework for how FSPs report complaints. The framework could include templates, definitions, and guidelines. An MCS typically would require FSPs to:

- Register complaints submitted through all channels (digital, phone, mail, in person)

- Note all complaints, including any that were immediately resolved

- Differentiate the reasons for closing complaint cases (e.g., complaint was resolved to the customer’s satisfaction, complaint was rejected because it did not pertain to a product or service being offered)

Granular data from regulatory reports

Market monitoring also uses the granular data that underly aggregated complaints. These data provide the greatest level of detail on FSP operations with customers and are valuable for measuring certain risks. For example, an MCS monitoring consumer loan risks may choose to monitor the indicator of number of complaints received in relation to the number of loans at the FSP level on a quarterly basis. To monitor this indicator, the MCS has the following options:

- Collect the ready-made indicator from FSPs

- Collect the ready-made numerator (total number of consumer complaints each FSP received in the quarter) and denominator (total number of each FSP’s outstanding loan contracts by the end of the quarter), then calculate the indicator using these two data points

- Collect granular data, including:

- A complete list of complaints received in the quarter to calculate the numerator

- A complete list of loans outstanding at the end of the quarter to calculate the denominator

The MCS may feel more inclined to collect ready-made aggregated data (options 1 and 2 above), as this requires the least amount of resources. However, these data are also the most rigid and allow the MCS no room to complete other types of analyses. Granular data (option 3) would allow the MCS not only to recreate the ready-made data but to run other data queries, conduct additional and deeper analyses, spot broader sets of patterns and issues, and construct additional or alternative indicators based on supervisory needs. It is useful for MCSs to thoughtfully and strategically balance these pros and cons when deciding what to monitor, which data are needed, and the most efficient way to obtain the data.

Data from MCS complaints handling and dispute resolution functions

In some jurisdictions the authority responsible for conduct supervision responds to consumer complaints or has a dispute resolution function as well. In addition to receiving consumer complaints, an MCS may receive inquiries through a customer service or orientation desk, a chatbot, or a social media channel. It may also have an office that registers consumer calls to sanction certain FSPs. In such cases, the authority would integrate all this information into market monitoring activities, including complaints data analysis, and explore measures for anonymizing information to protect consumer privacy. Over the long term, authorities that have adopted more sophisticated technologies to process unstructured data such as complaints narratives would incorporate these as well.

Information from alternative (out-of-court) dispute resolution mechanisms

An MCS can complement the information submitted by FSPs and complaints received directly from consumers with aggregated or detailed information on complaints handled by dispute resolution mechanisms. These may include statutory or voluntary public- or private-sector ombudspersons, mediation, or arbitration schemes. It is important that the MCS have access to this information in at least the same frequency and detail as the information it requests from FSPs, so both types of information can be compared and used in conjunction to provide a comprehensive picture of consumer risks and problems.

Other sources

An MCS can also request information from other authorities (e.g., the telecommunications regulator, the general consumer protection authority, the competition authority), consumer associations, industry associations, and research firms, which may be gathering periodic information on financial-sector consumer complaints. Additionally, the MCS can use technology providers to gather information on consumer complaints and issues as reported in online reviews or social media.

Back to top ↑

How to use this tool

Incorporating complaints data into market monitoring does not need to be an expensive or elaborate process. An MCS can start with data it already has from regulatory reports submitted by FSPs, or complaints directly submitted by consumers, and strategically add more advanced supervisory technologies over time to collect and analyze complaints data.

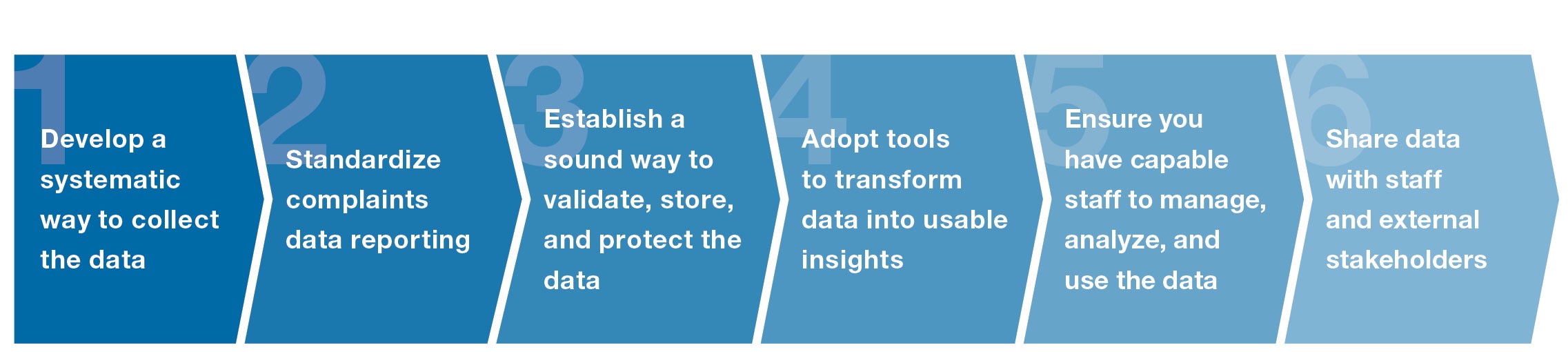

There are six key steps to consider when implementing this tool:

STEP 1:

DEVELOP A SYSTEMATIC WAY TO COLLECT THE DATA

This can be achieved through different platforms, depending on the source of the data. Collection tools may range from basic web portals that interface with FSPs, other regulators, and customers to advanced technologies such as smartphone applications or chatbots that directly connect an MCS with consumers. The MCS can also use social listening or web scraping tools which connect it to the marketplace to learn about customer experience. It’s important that the MCS consider the costs FSPs may encounter with enhanced data collection and ensure the compliance burden does not outweigh the overall benefits of collecting information. For example, the cost of reporting granular complaints data can vary according to factors such as whether desired data points (e.g., customer gender) are already available in an FSP’s information system. The MCS should closely consult with FSPs before imposing significant new requirements, including determining realistic implementation schedules.

STEP 2:

STANDARDIZE COMPLAINTS DATA REPORTING

To meaningfully use complaints data for market monitoring purposes, the data collected from FSPs needs to be standardized. The MCS needs to set up common definitions for the different types of complaints (or nature of the problem consumers face) that FSPs report on. If reports require data organized by product type or other criteria (e.g., complaints status), the MCS needs to set up common definitions to ensure the data are comparable across FSPs. In addition to these definitions, the MCS will need to impose common formats for each data field of regulatory reporting templates to ensure the collected data are useable.

STEP 3:

ESTABLISH A SOUND WAY TO VALIDATE, STORE, AND PROTECT THE DATA

The data need to be stored in a database that can integrate information from different sources (including manual submissions), interface with other IT systems, and allow access by designated users for analysis and follow up. The MCS needs to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the data, for example, by testing and validating information at onsite FSP exams or by automating plausibility checks. Due to the personal information consumers typically provide during the complaints process, it is important for the MCS to ensure strict data privacy and security protocols when analyzing granular data.

STEP 4:

ADOPT TOOLS TO TRANSFORM DATA INTO USABLE INSIGHTS

Options run the gamut from simple to sophisticated. At the simple end of the spectrum are tables with different types of aggregated data that can be used to construct indicators, plus formats that may vary slightly—depending on whether information comes from FSPs or other actors. In the middle are widely available software programs that filter and sort aggregated or granular complaints data by product or provider type to discern high-level trends. At the other end of the spectrum are data analytics that mine structured and unstructured granular data for patterns that indicate potential consumer harm. Examples include tools that scan complaints narratives and documents submitted by customers for key words, as well as algorithms that flag unusual spikes or statistical anomalies.

To help decision makers translate data into analyses and analyses into supervisory response, outputs from tools need to be incorporated into an analytical framework that describes the methodologies used, provides reporting guidance, and outlines standardized procedures. With so many available options, it is advantageous for the MCS to take the time to develop a sound strategy and prioritize tools that are the most relevant and cost effective based on perceived risks, staff skills and experience, and management information needs. As capacity grows and risks evolve, additional tools can be incorporated as further building blocks.

STEP 5:

ENSURE YOU HAVE CAPABLE STAFF TO MANAGE, ANALYZE, AND USE THE DATA

It is critical for the MCS to have market monitoring tools which are not so complex that they exceed staff ability to competently and effectively manage, analyze, and use them. Managing databases and analyzing data may require experts, such as data scientists and data analysts, who have technical skills that may be new to some authorities. It is equally important to have experienced supervisory staff that possesses the requisite judgment and skills to translate data analyses and reports into sound supervisory decisions. The MCS should avoid purchasing or using tools that are not readily understood or explainable (i.e., black box tools promoted by software suppliers).

STEP 6:

SHARE DATA WITH STAFF AND EXTERNAL STAKEHOLDERS

Those responsible for collecting and analyzing data will, at some point, need to securely share it with others inside and outside the organization. For example, examiners require timely access to complaints information for onsite and offsite reviews, while law enforcement and other financial sector regulators may require complaints data that is externally transmitted. The MCS needs to establish technical systems and procedures to ensure sensitive data is appropriately handled and securely transferred or shared.

Back to top ↑

Limitations of this tool

Although complaints monitoring is a valuable input to MCS work, there are limitations to consider:

- Limited depth. Complaints do not provide a complete view of the market on their own. They are anecdotal information that must be paired with an experienced supervisor’s judgment before firm conclusions can be drawn or enforcement actions taken. Gathering data from multiple sources provides a more comprehensive view of consumer problems, but it also requires greater effort to standardize definitions, content, and frequency.

- Unrepresentativeness. Complaints are subject to self-selection bias and do not give a statistically valid view of consumer issues in the market. Some consumers may be more likely to complain due to characteristics such as age, income, education, or gender, while others may never report the problems they experience. In the latter case, the MCS can proactively use tools like surveys and focus groups to detect unreported consumer harm.

- Reactivity. Complaints data are also lagging indicators of problems consumers have already experienced and may not allow for preemptive measures. For example, issues with long-term products such as life insurance may not surface until they are too late to remediate.

- Resource intensiveness. The collection and analysis of quality granular complaints data through traditional technologies consumes significant time at any MCS. When complex technology is used, more intense use of skilled resources is also required. Otherwise, analysis may lead inexperienced or poorly trained staff to draw inadequate conclusions. Data analytics can deliver false positives, false negatives, and spurious correlations, whereas inadequate understanding of complex, opaque models may impact the validity of conclusions.

Back to top ↑

Other resources

- Innovative Technology in Financial Supervision (Suptech)—The Experience of Early Users (Financial Stability Institute (FSI) 2018)

- Suptech: Leveraging Technology for Better Supervision (Toronto Centre 2018)

- SupTech Tools for Market Conduct Supervisors (FinCoNet 2020)

- The Next Wave of Suptech Innovation: Suptech Solutions for Market Conduct Supervision (World Bank Group 2021)