Market Monitoring FAQ

Market monitoring is a supervisory activity that takes a broad look at an industry, sector, or market (e.g., the credit market) as opposed to focusing on individual financial services providers (FSPs). However, market monitoring can and often does trigger institution-focused supervisory actions (e.g., inspections). Market monitoring is an integral element of financial consumer protection and market conduct supervision. It typically involves offsite supervisory tools and techniques that may be combined with other efforts, such as focus groups, consumer surveys, and mystery shopping. Market monitoring is an ongoing and systematic effort. Some activities are repeated over time to support the benchmarking comparisons and trend analyses that are the basis for risk-based and forward-looking supervision.

Other actors sometimes perform market monitoring to complement or support the work of the market conduct supervisor (MCS). For instance, an academic or research institution may conduct regular consumer surveys that the supervisor later calls upon for information.

Market monitoring plays an important function in consumer protection supervision and may lead to various benefits. It can be used to understand consumer risks, spot emerging risks that have yet to fully materialize, monitor market developments (e.g., the use of artificial intelligence in lending decisions), assess and monitor regulatory compliance, track consumer behavior and preferences (e.g., the use of digital payments and channels), follow consumer sentiment toward FSPs (e.g., negative/positive tweets), and measure customer outcomes (e.g., loss of money after a security breach). Market monitoring complements the institution-focused activities of market conduct supervisors. In fact, one of the weaknesses of institution-focused activities is that they do not sufficiently allow supervisors to spot emerging consumer financial-sector risks before they crystalize. Supervisory failure to identify and act upon emerging risks is often linked to the failure to conduct effective market monitoring.

For this reason, market monitoring is especially useful in the context of rapid change, such as in digital financial services, as it can provide more timely insights about the emergence or prevalence of the risks or harm consumers face and facilitate deeper analyses of vulnerable segments such as low-income women or female farmers. These benefits can transcend analyses performed at the individual provider level. By enabling a dynamic and preemptive view of the evolution of consumer issues and trends over time, market monitoring provides valuable input into the development of a risk-based supervisory approach and a consumer protection framework focused on customer outcomes.

Finally, the findings of market monitoring conducted by supervisors and other actors can be of special relevance to regulators and can contribute to evidence-based policymaking. By extension, effective market monitoring may become one of the richest sources of information to help international donors and funders decide the best ways to support supervisors in developing economies.

Although market monitoring is widely used by market conduct supervisors, there is no single formula for monitoring each individual context. There is also no straightforward answer to the question, “what is the best market monitoring tool?” The frequency various tools are used varies according to a supervisor’s objectives and factors such as budget, level and severity of risks, availability of quality data, and data analytics capacity. For instance, in most contexts the frequency of regulatory report analysis is higher than the frequency consumer surveys are conducted. However, some supervisors with large budgets can conduct more surveys than those with tighter resource constraints.

Yet no single tool suffices for all scenarios. Building an effective market monitoring framework requires a mix of tools. Resource constraints in the early stages of market monitoring implementation may limit the supervisor to analyzing aggregated indicators already collected through standardized, quantitative regulatory reporting. However, a wider range of data, tools, and techniques can gradually be deployed as resources become available and supervisory objectives increase in complexity.

The tools described in this toolkit are not mutually exclusive and supervisors will use them in different combinations. But regulatory reporting is the one tool that must be used in all combinations. When deciding to invest in a new tool or to improve an existing one, it is crucial to know your priorities. Fixing quality issues in regulatory reporting should be a top priority for every supervisor—even higher than investing in other tools. Suptech can considerably improve regulatory reporting, and the cost of suptech investment for this purpose depends on factors like existing data collection mechanisms used, provider legacy systems, number of providers, and type of suptech tool chosen by the supervisor. If your regulatory reporting data is already of high quality and has the desired level of granularity, you may encounter less urgency or less need to invest in complementary tools. As regulatory reporting becomes stronger, more opportunities will emerge to invest in different tools—including suptech, based on your supervisory needs and objectives plus your data gaps. Setting up a data strategy can help you plan and implement data improvements.

Finally, market monitoring itself does not produce changes in market practices that lead to positive consumer outcomes. Alongside institution-focused activities, market monitoring tools gather the evidence that allows supervisors to take necessary actions at the institution or market level that aim to generate desired outcomes. It is unlikely, for instance, that a supervisor will take an action against a provider solely based on a mystery shopping exercise or from social media insights. If the evidence collected from tools and the data obtained from regulatory reporting point in the same direction, the supervisor has a much stronger basis for action.

For the purposes of this toolkit, no. CGAP uses the term “offsite supervision” to refer to offsite procedures that typically follow a schedule of individual FSP “examinations.” The term “market monitoring,” on the other hand, looks at a sector as a whole, with consumers and their relationships with FSPs being the key target of analyses. One of the main objectives of offsite supervision is to assess the consumer risk profile of individual providers, while one of the main objectives of market monitoring is to spot emerging consumer risks at a market level. There is a fine line between these two types of supervisory activities since both use data as their main input and both (mostly) take place offsite. The terms are also used differently from country to country. For example, “offsite supervision” in one country could include the market-level analyses referred to in this toolkit as “market monitoring.”

At the country level and as a part of market conduct supervision, market monitoring is situated within a competent financial supervisory authority that holds a financial consumer protection or market conduct mandate. When multiple groups conduct financial supervision, it is important to clarify the mandates of different authorities and the division of roles within single authorities.

The location of the market monitoring function within a financial supervisory authority depends on factors such as the availability of resources and the size of sectors to be monitored. For larger sectors, market monitoring can be centralized to a specialized and dedicated team. For smaller markets, the function can be situated with the same team that conducts institution-focused market conduct supervision. In all cases it is important to clearly define work programs, roles and responsibilities for market monitoring that are separate from prudential supervision —and that complement institution-focused supervision. Such clear definition ensures the allocation of adequate market monitoring resources.

Other authorities and stakeholders, such as academic and research organizations and international funders, may complement and support the role of the market conduct supervisor. Skillful coordination between actors reduces the risk of duplicative and contradictory efforts.

In the strictest sense, no. Market monitoring as a supervisory activity primarily covers regulated markets over which market conduct supervisors have supervisory powers. In most cases, traditional tools like regulatory reporting and thematic reviews are only applied to regulated entities. Most supervisors do not have legal powers; for example, they cannot require regular data reporting from unregulated providers.

However, there is value in monitoring unregulated sectors to detect illegal activities or consumer harm, to assess their overall growth or prevalence in certain consumer segments, and to identify regulatory reforms needed to expand the supervisor’s purview. Monitoring may be carried out by the supervisor or it may be the focus of activities conducted by actors such as the consumer research or policy unit within a financial supervisory authority, the consumer protection authority, international funders, industry associations, and research organizations. Tools can vary but most often involve consumer surveys, interviews, and mystery shopping. Suptech tools such as web scraping or crawling and social media monitoring may be particularly useful in scanning unregulated activities since they do not require data requests from unregulated actors and are more efficient than manual procedures. The amount of effort put into monitoring unregulated markets varies according to existing concerns (e.g. suspicion of abuse by unregulated lenders, suspicion of illegal deposit-taking such as pyramid schemes) and, naturally, available resources.

At the most basic level, market monitoring involves the analysis of quantitative and structured data reported by regulated FSPs. These activities require staff that has basic data analytics skills (e.g., data crunching via common database management and spreadsheet software like Microsoft Access or Excel). Larger volumes of data collected at a higher level of granularity require staff with more advanced skills, such as programming languages that make data analysis faster and visualization tools to improve analyses presentation. More specifically, processing large volumes of unstructured data may require additional skills and tools to automate collection and analysis. For example, receiving standard-form consumer contracts and aiming to automate key word and phrase scanning and quickly analyze contract terms requires expertise in areas such as Boolean searches (depending on the technology tool used), big data analytics, machine learning, network analyses, natural language processing, and topic modeling, among others. It also requires additional software, which can be externally procured from a vendor or developed in-house. Dealing with data is only a means to an end; the ultimate goal is to arrive at useful supervisory insights. This requires staff with the appropriate skills and experience, including deep knowledge of consumer protection issues, laws and regulations, regulated products and providers, and a commitment to supervisory objectives.

If you are a market conduct supervisor, chances are you already collect or have access to a broad range of data reported by FSPs. Regulatory reporting, including but not limited to complaints data, is usually the baseline for market monitoring for consumer protection. Start by listing your supervisory objectives (based on the legal and regulatory frameworks in place) and identify the basic indicators you need to monitor under each objective. If the data is not deep enough to produce such indicators or has quality issues, first create a roadmap (data strategy) to improve it. Your data strategy identifies opportunities to invest in system improvements to standardize or integrate information collected through disparate databases. It also pinpoints the additional tools required to capture emerging consumer risks or market practices and deal with the wide range of unstructured data your team may already handle (e.g., draft or actual consumer agreements, marketing materials). Since supervisors spend most of their time analyzing unstructured data, any opportunity to increase efficiency is welcome.

The term “tool” is loosely used throughout this toolkit to refer to different types of analytical operations and data-gathering procedures. A tool does not necessarily mean a specific type of software or technology. For instance, analysis of regulatory reporting data is considered to be a tool because regulatory reports are usually the first source of information a market conduct supervisor can access. Reports are typically submitted in highly structured forms, with predetermined data fields that expedite easier data upload, usage, and storage in dedicated databases. Regulatory reporting in many countries entails submitting unstructured data reports in Excel and PDF formats. The required reporting of consumer contracts is a good example: although contracts are collected through regulatory reporting, contract analysis is considered to be a separate tool because the collected data (which is unstructured and primarily qualitative) varies.

Not all tools require investing in suptech, which uses advanced analytics and combinations of data types. However, one of the greatest advantages of gradually investing in suptech is enhancing the use of the abundant unstructured data that market conduct supervisors collect. Suptech also increases a supervisor’s ability to collect, analyze, and visualize large sets of structured data, as well as to combine structured and unstructured data. Additional information on suptech can be found in the Suptech FAQs: a quick reference to existing guidance from the World Bank, FinCoNet, and other sources. The Suptech FAQs [see section below] also provide market conduct supervisors with suggestions on how to select suptech vendors, costs associated with suptech solutions, and how to set priorities for suptech investment.

Collecting and analyzing gender-disaggregated data can strongly support policy objectives—from prudential supervision and market conduct supervision to financial inclusion. From the perspective of market conduct supervision, incorporating gender-disaggregated data into market monitoring is essential for identifying instances of poor conduct and consumer outcomes that impact specific segments, such as women or vulnerable populations. Analysis of granular gender-disaggregated data (e.g., demographic, transactional, financial, and operational components) can yield significant insights about the discriminatory practices and biases women and minority groups face, including higher interest rates and insurance premiums; higher rejection rates for loan applications; and longer complaints resolution times. Gender-disaggregated data can help identify gaps in the access, use and quality of financial services and support the design of policies to bridge those gaps. Supervisors can request that regulated institutions collect information about customer gender and include it in their regulatory reports (see analysis of regulatory reporting).

Suptech FAQ

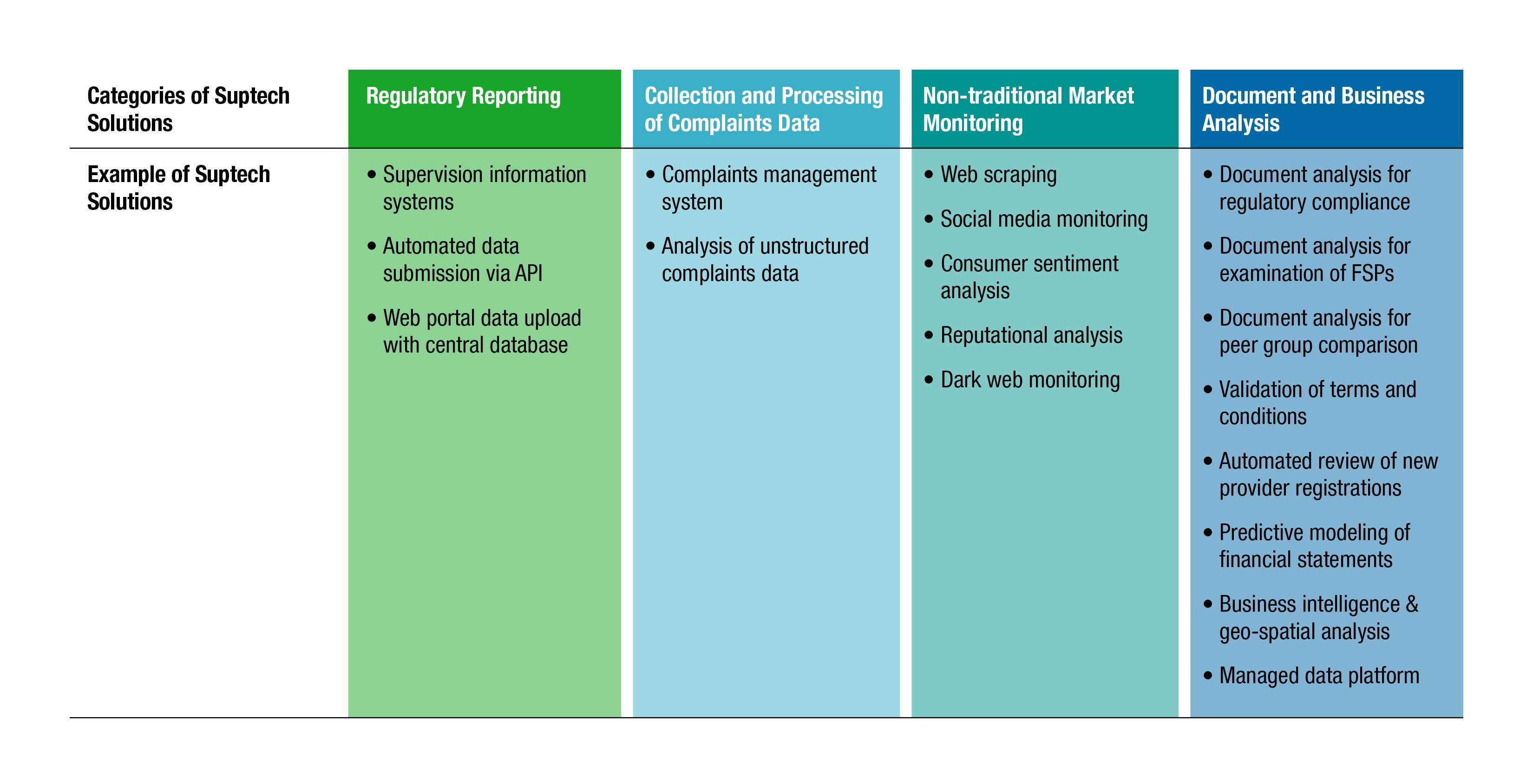

Supervisory technology (suptech ) is the use of technology to improve supervisory effectiveness and efficiency. Suptech includes:

- The use of innovative or cutting-edge technologies (e.g., artificial intelligence, natural language processing)

- The use of traditional technologies in a way that allows innovative supervision methodologies (e.g., process digitalization and automation, new ways of using databases)

A recent FinCoNet survey of 21 market conduct supervisors (MCSs) found that traditional technologies are used more frequently, primarily to process structured data (i.e., data with standardized elements). At the same time, MCSs are increasingly applying innovative suptech solutions to collect and analyze unstructured data, such as text from complaints narratives. Many different types of suptech solutions correspond to the four generations of technology (i.e., 1G–4G) across five data functions: collection, processing, storage, analytics, and visualization. Click here to see how these functions have evolved through each generation.

Suptech can be used to support multiple stages of market monitoring. A market conduct supervisor (MCS) can use suptech solutions to identify and prioritize consumer risks or issues at the preparatory stage, as it develops supervisory plans or determines the scope of a thematic review.

Suptech may be the data collection or analysis technique behind some market monitoring tools. For example, MCSs can use suptech to improve interfaces and reduce compliance costs for regulatory reporting by financial services providers (FSPs). Suptech can be employed to analyze large volumes of consumer complaints, to monitor social media advertising, or to assess whether consumer contracts comply with market conduct regulation.

Another emerging suptech use case is streamlining workflows and analyses of market monitoring activities. For example, suptech can automate or speed up labor-intensive tasks and processes via solutions such as extensible business reporting language (XBRL, an international open standard for digital reporting), interactive visualizations, and artificial intelligence for data analysis.

Suptech solutions have many uses related to data collection and analysis. For example:

Data collection. Suptech helps overcome challenges with collecting structured and unstructured data, including insufficient granularity, redundancy (different disclosures or templates that provide the same information), manual aggregation (especially for large FSPs with multiple systems for generating various templates), low quality (missing data points, errors in calculation and coding), and manual validation.

Collection of standardized structured data. E-reporting is a type of suptech tool that aims to reduce or eliminate laborious routine manual tasks tied to regulatory reports handling. By automating data validation, e-reporting mitigates human error and improves data. (The Mexico case study provides an example of e-reporting.). The main features of e-reporting include:

- New reporting interfaces with FSPs

- Reporting taxonomy that clearly defines each regulatory report in a structured, machine-readable way

- Secure reporting channels

- Automatic validation and transformation to ensure data quality

- Raw information reporting by FSPs (granular data without transformation)

E-reporting can be carried out via two main groups of suptech solutions: (i) tools to fill in data (e.g., XBRL, Excel spreadsheets, CSV), and (ii) tools to exchange data (web-based systems and portals, server-to-server encrypted channels, APIs). Solution selection depends on data volume, rapidity of exchange, and the technological and financial resources of both market conduct supervisors (MCSs) and financial services providers (FSPs).

Collection of unstructured data. Innovative data collection tools like web scraping and social media monitoring applications focus on collecting and converting unstructured, publicly available data into structured data. Information is collected from a range of sources, almost in real time.

Data analytics for unstructured data. Machine learning-based applications allow for the automated and accelerated analysis of unstructured data, based on identification of patterns, trends, and continuous inference. For example, natural language processing (NLP) provides automated mechanisms to read or listen to human language, transform it into computer code, and perform tasks such as identifying relevant topics or summarizing text.

NLP facilitates (i) text mining, which is the process of deriving high-quality information from unstructured text—typically by finding patterns and trends, and (ii) topic modeling, which is the use of statistical models to identify recurring themes across multiple documents. NLP allows an MCS to thoroughly analyze large volumes of information rather than perform the traditionally limited analysis of small samples of information. Successful use cases include the monitoring of unfair contract terms, social media monitoring, and customer complaints analysis.

Suptech solutions are beneficial for improving the quality and efficiency of day-to-day monitoring and supervision. For example:

- Workflow improvement. Suptech can help a market conduct supervisor (MCS) to automate workflows, streamline and expedite day-to-day processes, connect various data sources, and manage communication among consumers, financial services providers (FSPs), and authorities. For example, suptech can improve complaints data management and analysis.

- Development of conduct risk profiles and early warnings. Suptech can develop automated systems that carry out efficient analysis on large numbers of FSPs, build their risk profiles, and rapidly detect early warning signals.

While suptech solutions can be highly useful in monitoring market conduct, they may also introduce or increase risks. While not an exhaustive list, the following potential risks illustrate key issues to consider when planning a new suptech solution:

Data quality and reliability risks

- False alerts or erroneous outputs from poorly designed algorithms

- Opaque machine learning tools whose output cannot be explained (black box)

- Incorporating and reinforcing human bias in suptech algorithms

- Excessive reliance on data analytics, a.k.a. “data blindness,” and losing sight of qualitative (or even quantitative) aspects not captured by suptech

- Unreliability and low quality of certain types of big data (e.g., social media)

- Potential for third-party manipulation of big data used as suptech input. For example, FSPs may try to “game” MCS algorithms via bots that post fake social media messages in their favor or against a rival FSP, or by changing model consumer contracts after learning about specific terms the MCS has searched

Data unrepresentativeness

- Data does not represent all consumer segments. For example, some segments may not feel comfortable posting on social media, may find it too costly or difficult due to lack of access to a digital device, or may prefer other communication channels

- Data does not capture all main consumer issues

Data privacy, security, and operational risks

- Heightened cyber security and data security vulnerabilities

- Increased third-party dependency (e.g., cloud computing, algorithm providers)

- Other operational risks (e.g., disruptions to power or communication)

- Data privacy risks, including alternative data such as social media

The term “suptech strategy” can be interpreted in different ways, depending on whether it has been formulated at the board level or at lower levels within a market conduct supervisor (MCS); whether it has been formalized and approved in a written document; and whether specific suptech developments have been initiated. In practice, a formal strategy is not always necessary for a successful suptech pilot, especially in developed countries, because the first stages of suptech development often use a bottom-up approach (i.e., solving one problem faced by one supervisory team). For example, Banco de Portugal started investing in suptech by piloting a solution to a specific problem: the need to reduce the time supervisors take to analyze consumer contracts. A successful suptech pilot is now being scaled up as part of an initiative to revamp the bank’s entire data infrastructure.

However, a suptech strategy may be quite useful to an MCS in an emerging market for assessing how suptech tools will address specific data gaps, align with strategic supervisory objectives (a top-down approach), and complement or replace investment in other tools. A suptech strategy contributes to effectively integrating sustainable suptech efforts into MCS work, considering resource constraints and overall supervisory priorities.

Most MCSs that participated in a recent FinCoNet survey had a suptech strategy. But rather than formulating a suptech strategy, some MCSs employ a broader data strategy[link to Taking Action] that plays a similar role in suptech investment. Examples include the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) and Banco de Portugal.

Above all, a successful suptech strategy is tailored to your unique context and circumstances. Important elements to cover include:

- Supervisory and policy objectives that could be enhanced by suptech

- Achievable targets

- An assessment of the current environment (e.g., data availability, data quality, analytical resources)

- Priority areas for suptech investment

- Specific solutions to be explored or the process used to identify specific solutions

- Infrastructure and organizational resources needed, including storage capacity and training data required for algorithm development

- Approach to integration with legacy systems

- Risks and limitations of suptech solutions

- Implementation challenges

- Risk management framework, including cyber risk

- Vendor selection criteria

- Vendor management process, including retention of source codes

- Algorithm management and governance

- A step-by-step implementation action plan

Choosing a suptech solution depends on stated objectives, data needs, and budget. Each data need may require a different solution, and a combination of needs may impact the priority of your decisions about which solutions to adopt. This emphasizes the importance of developing a suptech strategy that keeps the bigger picture in sight. (See FAQ #18, “Where can we learn more?” for resources that contain examples of solutions that market conduct supervisors (MCSs) have chosen to solve their monitoring and supervisory challenges).

If the choice is still not immediately apparent, some innovative approaches can help an MCS narrow down potential suptech solutions to make a final choice:

- Innovation labs or innovation centers set up as units or programs within a supervisory authority, which allow technical solutions to first be internally tested for each supervisory use case in a secure development environment.

- Example: Banco de Portugal created an innovation lab to find ways to streamline supervisory processes such as the use of natural language processing (NLP).

- Innovation accelerators, either one-time or ongoing programs involving outside parties, which develop exploratory proofs of concept or prototypes in a defined timeframe to demonstrate the viability of a certain solution or concept prior to deciding whether to invest in it.

- Example: The Bank of England has published the results of many proofs of concept for potentially modernizing its supervisory activities in areas such as digital regulatory reporting and data visualization.

- Tech sprints, hackathons, or codeathons, like accelerators, seek to develop proofs of concept but in a much shorter timeframe in the form of intensive two-to-five-day workshops. They bring together internal experts plus vendors and other outside experts around specific challenges and use cases. During these events, vendors go from ideation to development to proposal of a technical solution. An MCS can then compare and choose whether any of the solutions fit its needs and can be implemented.

- Example: The UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) has pioneered tech sprints since 2016, summarizing lessons and challenges in a recent publication. The Central Bank of Argentina has co-organized financial innovation hackathons since 2016, including calls on regulatory or supervisory challenges in consumer protection and financial inclusion.

- Challenges or public requests for proposals on solutions to a problem posed by the regulator.

- Example: The Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) partnered with the Department of Industry, Science, Energy, and Resources to launch a challenge for innovators. The idea was to propose a technology solution to analyze market announcements and other corporate disclosures by listed companies and entities to identify and assess poor market disclosure. The goal was to increase ASIC’s efficiency and effectiveness in supervising and enforcing business conduct, plus disclosure and reporting obligations by listed companies, since most of its supervisory activities are currently manual.

Throughout the decision-making process, it is important to consider suptech a continuous learning process rather than a one-time investment. Even an already-implemented tool can be improved, while its architecture and concepts can also be applied for other purposes.

Many suptech projects can be collaboratively developed in-house (with or without external vendors) between an MCS and its IT department. This strategic decision is based on whether the MCS wants to (and can) invest staff time and resources to develop suptech alone—or prefers third-party outsourcing. Purchasing from an industry vendor may make sense on complex projects, allowing the MCS to more quickly complete a project due to resources, technical expertise, and experience. It is likely the MCS will end up using a combination of solutions to tackle its various supervisory problems.

A market conduct supervisor (MCS) may find it challenging to amass comprehensive knowledge about the pool of potential suptech vendors, which range from small startups to well-established global technology firms. (For reference, R2A offers a list of vendors and their main areas of expertise.) While standard procurement procedures need to be observed, the MCS can benefit from innovative approaches such as innovation accelerators, tech sprints, and challenges (see FAQ #8) to not only understand and compare potential solutions, but also to amass a pool of vendor candidates.

Selecting a vendor for a particular solution must be based on clear criteria such as technical expertise, ability and willingness to pilot prototypes before full contractual commitment, strong cost-benefit analyses, or previous work with supervisors.

When engaging an external vendor, the MCS needs to have a clear concept of which data gap needs to be addressed (e.g., sweeping the internet to collect marketing materials on a specific type of product) and the desired supervisory objectives the suptech solution will contribute to (e.g., reducing staff time currently allocated to a particular task). Vendors most often specialize in solutions to private-sector problems rather than supervisory problems. This is one reason off-the-shelf solutions rarely meet an MCS’s needs. Customization is almost always required; the MCS must be heavily involved in developing the solution’s specifications, rather than leave IT department programmers and data scientists to engage with the vendor. Subject matter expertise is also key to successful suptech project implementation.

Multiple vendors will likely be required to implement different suptech solutions to fulfil your priorities. It is useful to guide suptech implementation by first designing a strategy. This will ensure that your various tool implementation projects complement each other and are prioritized according to your supervisory objectives and data needs. Using suptech is a continuous implementation process that favors further development of tools once they are in use. Tools should be subject to periodic assessment in the same manner supervisory procedures are assessed.

Costs of suptech tools vary widely, depending on the project, and especially considering that most are developed with a combination of in-house and vendor resources. For this reason, it is difficult to put a price tag on an individual suptech solution. A suptech solution may be part of a larger project (such as a complete revamping of the data infrastructure and reporting mechanism of a supervisory authority) or part of a multiple-solution package negotiated with a vendor or a consortium of vendors.

Even comparing vendors for a specific solution is not a straightforward process. For instance, most vendors of social media monitoring solutions focus on commercial clients that want to track their brands on social media and do not follow consistent criteria to set their solution’s price. Some price the solution based on the number of data points collected, some on the number of analytical dashboards provided; others combine the two variables.

Price is also determined by the market conduct supervisor’s (MCS’s) own preferences. For example, an MCS with greater analytics capacity may prefer to purchase a “bare bones” solution and pay less than an MCS with limited analytics capacity that prefers built-in analytics capabilities (e.g., dashboards, visualization options, user-friendly filters). Typically, the more complete the solution the greater the cost.

An MCS should also consider combining vendors or in-house tools with open-source solutions available on the internet, including for big data analytics and advanced visualization tools. Their use could reduce the need for the MCS to purchase similar solutions from a vendor—as long as adequate data protection and privacy measures are taken.

Different users require different levels of training and expertise. Not everyone needs to be a data scientist, but a market conduct supervisor (MCS) engaged in suptech needs sufficiently specialized human resources to effectively use suptech. The MCS should consider its strategy to attract and retain staff with specialized expertise in data sciences and related expertise, as well as ensure that institutional knowledge is maintained should staff turnover reach high rates. Suptech increases the need for better risk management capacity at supervisory agencies. For example, if more data are digitally managed and sophisticated data analytics are outsourced to third parties or housed in third-party cloud environments, better cybersecurity and business continuity frameworks must be in place.

The most common challenges a market conduct supervisor (MCS) may face when implementing suptech include:

- Gaining buy-in and involvement by top management

- Clearly articulating suptech objectives and goals • Prioritizing suptech use cases

- Coordinating and managing relationships with internal and external stakeholders

- Overcoming budget or administrative constraints to procure suptech projects

- Need for highly qualified staff to support the development and management of suptech tools (e.g., data science, advanced analytics, data visualization), and a team dedicated to suptech project implementation

- Costs of upgrading manual processes and documentation at financial services providers (FSPs)

- Rigid existing legacy processes and systems

- Limited IT infrastructure to ensure adequate data availability, quality, standardization, and representativeness

- Data silos at supervisory agencies

- Finding customizable suptech solutions in the market

Some hurdles Canada’s Autorites des marches financiers (AMF) faced when implementing an artificial intelligence (AI) suptech solution include:

- Technologies based on AI need significant amounts of data to be effective.

- Adequate training required teams working on the tool to first build a database with large volumes of data.

- AI algorithms require data structured with labels.

- Dataset creation and labeling (the addition of meaningful data tags) are time-consuming.

- Machine learning still requires significant manipulation of the data, which is also time-consuming.

- Solutions require an iterative development process with input from subject matter experts.

Possible solutions to address common suptech implementation challenges

| Challenges | Solutions |

| Lack of management buy-in and resistance to change |

|

| Lack of financial resources |

|

| Need for skilled staff |

|

| Costs and |

|

| Cohesion with existing legacy systems |

|

| Underdeveloped IT infrastructure |

|

Source: Adapted from World Bank (2020).

It depends on where you are in your market monitoring journey [see Taking Action]. A market conduct supervisor (MCS) should prioritize strengthening its foundation, especially regulatory reporting, before considering suptech investment. Otherwise, suptech solutions may divert valuable scarce supervisory resources away from the supervisor’s most basic needs. Many MCS weaknesses cannot be solved with better technology. It is also important to keep in mind that innovation is not limited to the use of suptech—it encompasses the application of new procedures or institutional arrangements to market conduct supervision. An open MCS mindset is essential for effective use of suptech to achieve supervisory effectiveness.

Resources on suptech are abundantly available. The following resources have been consulted in formulating these FAQs and are a good place to start.

Fostering Innovation through Collaboration: The Evolution of the FCA TechSprint Approach (Financial Conduct Authority [FCA] 2020)

Innovative Technology in Financial Supervision (Suptech): The Experience of Early Users (Financial Stability Institute [FSI] 2018)

The Suptech Generations (Financial Stability Institute [FSI)] 2019)

From Data Reporting to Data-sharing: How Far Can Suptech and Other Innovations Challenge the Status Quo of Regulatory Reporting? (Financial Stability Institute [FSI] 2020)

Suptech Tools for Market Conduct Supervisors (FinCoNet 2020)

Suptech: Leveraging Technology for Better Supervision (Toronto Centre 2018)

A Roadmap to Suptech Solutions for Low Income (IDA) Countries (World Bank 2020)

The Next Wave of Suptech Innovation: Suptech Solutions for Market Conduct Supervision (World Bank 2021)

Back to top ↑

What do the standard-setting bodies say about market monitoring?

International standard setting bodies (SSBs) as well as other global bodies recommend the adoption of market monitoring by supervisors, including in terms of consumer protection, market conduct and financial inclusion. Below is a non-exhaustive list of examples.

“[…M]onitoring and surveillance are still needed to identify when certain players or sectors grow to such an extent that the risks become systemically significant, requiring a different approach. With new technologies (eg mobile phones and the use of non-bank agents) being increasingly deployed by financial institutions to serve low-income customers who were previously excluded from formal financial systems, the speed with which risk grows or concentrates in individual institutions may be different from that historically observed in conventional retail banking.”

“[…T]he supervisor should monitor the emergence of new products and services (eg through market monitoring, allowing providers to launch and test pilots with real customers in a monitored and controlled environment, or studying similar developments in other countries) and be ready to modify the list of permitted activities, as needed.”

“Authorities should pay special attention to individual and industry-wide competitive practices in unserved and underserved market segments to identify abusive or unfair business practices harming or limiting options for consumers. Responsive measures (eg recommendations, regulations, corrective actions, sanctions) should be taken in coordination with competition and other authorities, such as the telecommunications authority or payments overseer. The use of adequate monitoring and supervision tools (eg mystery shopping, focus groups, advertising review) can help authorities understand the market context and the effect of such abusive or unfair practices on consumers and take better-informed supervisory decisions.”

“Effective oversight of products which are offered to customers is fundamental to maintaining fair, safe and stable insurance markets and as such, effective oversight is considered a key responsibility and activity of the insurance supervisor. Further, supporting the development of the market, particularly in the context of inclusive insurance, may also be considered part of an insurance supervisor’s key objective. Effective requirements and monitoring of products can support the market’s development by ensuring that products are fair, sustainable, provide value and build a positive reputation for insurance amongst previously excluded customers.”

“The global financial crisis highlighted the importance of not only monitoring threats to individual institutions or groups, but actively monitoring risks to the stability of the financial system as a whole. The crisis demonstrated that systemic risks can arise not only through failings in individual institutions’ and groups’ financial and capital management, but also in poor conduct of business (COB) practices. The indiscriminate marketing and poorly targeted sales of sub-prime mortgage products is a well-documented example of how COB failings can contribute to systemic financial instability. […] Supervisors must have tools to detect as soon as possible any COB risks that could negatively impact individual policyholders, insurers and, potentially, the financial system as a whole.”

Reading Tip: Application paper on product oversight in inclusive insurance

“Supervisory authorities have a major role in monitoring and contributing to the enhancement of business conduct by pension services providers and their agents. [...] The role of pension supervisors may involve closely evaluating and monitoring the new products entering the market, as well as the marketing and advertising strategies used by the pension services providers and their agents for existing and new products.”

Reading Tip: The role of supervision related to consumer protection in private pension systems

“[T]he rapid pace of technology advancement makes it critical for supervisors to closely monitor developments in the entire financial industry. It is also important that supervisors educate staff on new technologies and build supervisory skills and resources to understand changes in the market at an early stage and to anticipate future developments. [...] Innovation occurring in the financial sector, including private pensions, has become an area of increased supervisory attention. Supervisors aim in the first place to offer support and foster financial innovation, through the organization of regular meetings, establishment of innovation hubs and/or regulatory sandboxes. In parallel, they also intend to closely monitor developments and address any emerging risks involved with FinTech for the financial sector and consumers.”

Reading Tip: Impact of digitization on financial services on pension supervisory practices: case studies

“[T]here may be value in taking an iterative approach to disclosure design and testing—monitoring the effects of new disclosures on behaviour and adapting as these effects change.”

Reading Tip: The application of behavioural insights to retail investor protection

“Regulators should have in place appropriate supervision and market monitoring measures to hold DFS providers accountable for consumer protection outcomes. These should include standardized, electronic reporting requirements for fraud, complaints, products, etc. Regulators should also consider using consumer research, such as mystery shopping and SMS or IVR surveys, and other consumer engagement. [...] Regulators should engage in regular consultations with digital credit providers, consumer organizations, and other stakeholders to stay apprised of market developments, including new digital credit products and services being offered, the types of providers offering them, and consumer experiences and risks associated with them.”

Reading Tip: ITU Focus Group on Digital Financial Services

"Since consumer protection is about the relationship between a financial services provider (FSP) and its customers, it has different criteria than prudential risk assessment […] Supervisory tools can also differ from those traditionally used in prudential supervision, such as mystery shopping, market monitoring and focus group research are more prominent in market conduct."

Reading Tip: Market Conduct Supervision of Financial Services Providers - A Risk-based Supervision Framework “Globally, digital financial services (DFS) are playing a key role in helping AFI members reach the underserved and unbanked. [...] However, these innovations are introducing new risks and challenges that need to be monitored carefully to ensure they do not create systemic risks to financial stability, jeopardize consumer trust or compromise financial integrity.”

Reading Tip: Global Policy Forum (GPF) 2018 Report

“To identify the potential risks of DFPS [digital financial products and services] and to design effective regulatory and supervisory measures requires monitoring the digital products and services in development by industry in each jurisdiction, and across borders.”

Reading Tip: Practices and tools required to support risk-based supervision in the digital age

“Supervisors should make use of a set of effective tools to oversee that the provision of STHCCC [short-term high-cost consumer credit] through digital channels complies with the applicable rules, including not only traditional but also innovative tools specifically designed for the digital environment.”

Reading Tip: Digitalisation of short-term, high-cost consumer credit. Guidance to supervisors

“Technological developments present a range of challenges and opportunities for domestic public authorities responsible for the oversight of financial consumer protection. […] Oversight bodies should ensure they have adequate knowledge of the financial services market. […] Oversight bodies should ensure existing regulatory and supervisory tools and methods are adapted to, and explore new avenues for operating effectively in, the digital environment.”

Reading Tip: Financial Consumer Protection Approaches in the Digital Age

“The speed of technological innovation in financial services and the specialised knowledge that may be required to understand the technical underpinnings of the services being developed implies that dedicated resources may be needed to monitor developments and the emerging risks and implications for financial consumer protection.”

“Financial markets will need to be carefully monitored to ensure that new and emerging business models and products are being appropriately regulated. Mechanisms need to be in place to quickly adapt to changes in the financial landscape.”

Back to top ↑

Other resources

Conduct: Prevention, Detection and Deterrence of Abuses by Financial Institutions (Toronto Centre 2016)

Good Practices for Financial Consumer Protection (World Bank 2017)

High-Level Principles for Financial Consumer Protection (G20/OECD 2011)

Implementing Consumer Protection: Technical Guide (CGAP 2013)

Making Consumer Protection More Customer-Centric (CGAP 2020)

Practices and Tools required to support Risk-based Supervision in the Digital Age (FinCoNet 2018)

Proportional Supervision for Digitial Financial Services (CGAP)

Regulating for Innovation Toolkit (Cenfri 2021)

Risk-Based Supervision in Low-Capacity Environments (CGAP 2019)

Supervisory Toolbox (FinCoNet)

UNCDF Policy Accelerator: Policy Tools and Resources (UNCDF)