Fair contract terms and conditions—and their effective disclosure to consumers—are key to consumer protection, particularly for vulnerable segments such as low-income women and previously excluded customers. Members of the Consumers International network have identified unfair contract terms and conditions as the third most important challenge for financial consumers in a 2021 survey covering 32 low- and middle-income countries.

Market conduct supervisors (MCSs) analyze the content of standard-form contracts and actual contracts used to govern commercial relationships between financial services providers (FSPs) and consumers.

- Standard-form contracts are the general, nonpersonalized documents FSPs often disclose on their websites and premises, or by other means. They may also be referred to as standard-form agreements or adherence contracts, and often include annexes that determine the complete contractual relationship. A key objective of analyzing this type of contract is to identify unfair or illegal contract terms and discover new products and services.

- Actual contracts are the confidential personalized contracts signed by customers that become the legal foundation and proof of a commercial relationship. They include actual terms such as interest rates, amounts, and the tenure of a financial product acquired by an individual customer. A key objective of analyzing these contracts is to assess whether specific consumer segments are treated fairly.

Analyses of these two types of contracts do not have the same objectives, so they complement rather than act as a substitute for each other.

Benefits and opportunities >

Characteristics of this tool >

How to use this tool >

Limitations of this tool >

Other resources >

Benefits and opportunities

Contract analysis offers several benefits:

- Responsiveness. It allows an MCS to identify and respond to noncompliance with regulatory requirements on contract terms, including by determining abusive or unfair contractual clauses and issues of accessibility and understandability of contract language.

- Proactivity. It can help an MCS to monitor new product launches and spot emerging risks before they become widespread.

- Timeliness. It can help an MCS to identify changes to product terms and contract clauses as quickly as it is able to conduct contract analysis.

- Segmentation. Analysis of actual contracts can help an MCS to identify discrimination (e.g., higher prices) against specific customer segments (e.g., older women, people living in certain areas).

- Dissemination. Publishing the overall results of ongoing contract analyses could lead to the improved accessibility of contractual language (i.e., make contracts easier to understand) and fairness in contract terms for widely used retail products. Consumer and industry associations and the media could use publications to push for better FSP practices.

Back to top ↑

Characteristics of this tool

MCSs in different jurisdictions use contract analysis in various ways. Some countries use the tool as part of their ongoing market monitoring activities, including Malaysia, Mexico, Peru, and Portugal. Many MCSs analyze contracts on an ad-hoc basis as part of an institution-focused examination (usually limiting it to a sample) or as part of a thematic review. In the latter case, the MCS would possibly analyze all standard-form contracts related to a financial product. The difference between these scenarios is discussed below.

TABLE 1. Types of consumer contract analyses

Back to top ↑

How to use this tool

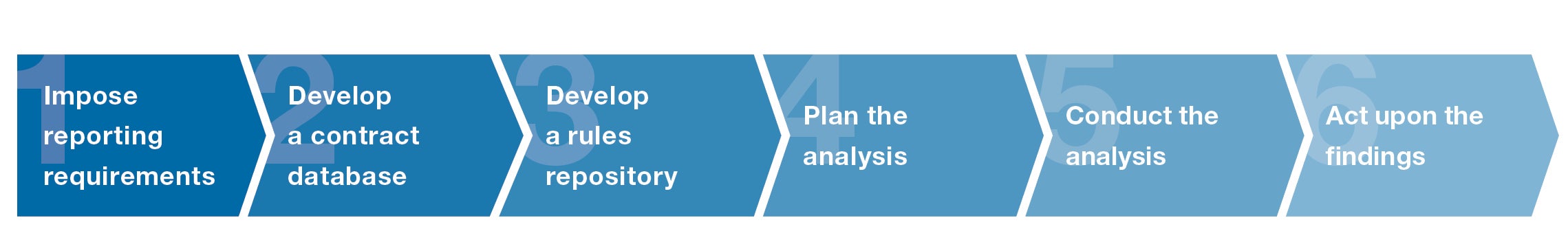

For MCSs with the capacity to conduct contract analysis as an ongoing market monitoring activity (i.e., an exercise to be periodically repeated), we propose the following six steps:

There are six key steps to consider when implementing this tool:

STEP 1:

IMPOSE REPORTING REQUIREMENTS

MCSs need to impose specific reporting requirements. For example, FSPs may be required to report all standard-form contracts for certain relevant product categories once a year, and immediately report previously unreported contractual changes or new standard-form contracts. Some MCSs require prior approval of new products or new standard-form contracts before adoption. In this case, there is no need to impose additional reporting requirements for market monitoring. If the product or contract approval process is conducted by another team within an MCS, interdepartmental coordination is required. For actual contract reporting, an MCS needs to determine a reporting frequency commensurate with its analytical capacity—considering the potentially high volume of documents that could be reported.

For both standard-form and actual contracts, the MCS should determine file format (e.g., PDF, Word) to facilitate storage, retrieval, and analysis. For example, depending on available technology, it may be best to avoid images or other formats that do not respond well to text searches.

STEP 2:

DEVELOP A CONTRACT DATABASE

The next step is to build a contract database to safely store collected documents and facilitate their analysis. Precautions that ensure data safety and integrity should be doubled when handling actual contracts since they may include a client’s personal information. Some MCSs choose to collect only actual contracts that are already anonymized by FSPs. The contract database needs an adequate system for categorizing and labeling different types of contracts, building on the development of a rules repository (see Step 3). Product categories may include consumer loans, mortgage loans, savings accounts, payment accounts, health insurance, disaster insurance, property damage insurance, and others. Contracts that are clearly labeled in the database make the job easier for analysts and, potentially, for automated tools.

STEP 3:

DEVELOP A RULES REPOSITORY

It is useful to develop a rules repository comprised of a list and description of all regulatory requirements that apply to each type of retail product, as well as brief instructions on how to analyze each, including examples of unfair terms and conditions, abusive and prohibited clauses, misleading or ambiguous terms, etc. A rules repository ensures a minimum level of consistency in analyses conducted by various analysts. It is a living document that continuously improves as experience with analyses increases, and as regulations and market practices change—a process called “rules management.” A rules repository can be a simple Excel spreadsheet that includes source regulations, requirements, and the products to which each requirement applies. A single requirement may apply to multiple products. Product categories in a rules repository should match those used to label documents in a contract database.

STEP 4:

PLAN THE ANALYSIS

The next step is planning the analysis. Most MCSs are unable to cover all rules, each contract, and every FSP—even if they have a team dedicated to contract analysis full time. An MCS needs to prioritize according to the risk-based methodology it uses to optimize supervisory resources. For example, based on the rapid growth of digital loans in a country, the MCS may decide that its priority for the year is to analyze digital loan contracts, specifically the following regulatory requirements: disclosure of a consumer warning on the consequences of defaulting on a loan, standardized disclosure of an annual percentage rate (APR), and length of a digital contract.

The most important consideration for an MCS as it embarks on contract analysis is to pursue clear supervisory objectives that follow a risk-based approach to supervision. The MCS could otherwise risk spending a significant portion of staff time without seeing tangible results. It is also important to keep in mind the timing element of standard-form contract analysis. For example, an analysis may become meaningless if it is performed too late and the risks posed by abusive contractual terms and conditions have already materialized and affected a large number of consumers. At that point the results of the negative terms and conditions may already be reflected in other sources of information, such as complaints data. To the extent possible, the time lag between collecting and analyzing standard-form contracts should be minimal.

STEP 5:

CONDUCT THE ANALYSIS

The objectives for conducting the analysis of standard-form contracts and actual contracts differ. One type of analysis does not replace the other.

A standard-form contract analysis carries the following potential objectives:

- Checks for the presence of minimum contractual elements (e.g., name and address of FSP and client)

- Checks compliance with specific consumer disclosure requirements (e.g., mandatory clause that warns consumers of certain risks, inclusion of a standardized effective APR)

- Checks compliance with broader transparency requirements (e.g., plain language)

- Checks for presence of prohibited contractual clauses or terms and conditions (e.g., imposition of arbitration, forgoing recourse rights)

- Checks overall fairness of contractual terms and conditions (e.g., responsibility for unauthorized transactions)

An actual contract analysis, on the other hand, usually focuses on additional objectives that cannot be achieved through standard-form contract analysis. Actual contract analysis is particularly useful for spotting discriminatory treatment such as women facing higher interest rates on loans or higher insurance premiums. For example, contract analysis may check whether an APR is calculated and disclosed according to regulation or monitor geographic and demographic trends in service provision. While an MCS may sample actual contracts during an onsite inspection to confirm whether they match standard-form contracts, this is not the objective of analyzing actual contracts as a market monitoring tool.

Opportunities exist to combine different types of market monitoring tools. For example, contract analysis may be combined with and complemented by analyses of complaints on specific products— some of which may relate to issues brought to light by contract analysis. An MCS may also analyze information on “rejected clients”—those whose loan applications have been rejected by FSPs—to confirm any suspicions raised by contract analysis about discrimination against certain client segments.

STEP 6:

ACT UPON THE FINDINGS

Contract analysis most often leads an MCS to act upon findings at the FSP level rather than the market level. The most common action spurred by standard-form contract analysis is to require individual FSPs to make changes to their standard-form contracts. Problems in actual contracts may lead to warnings; client reimbursement or compensation, if warranted; and even remedies such as requiring an addendum when a contract is still in place. When a market monitoring team is different from an FSP’s supervision team, FSP-level actions will require interdepartmental coordination.

If analysis spots significant weaknesses in standard-form contracts that could harm a large number of consumers or cause a small number of consumers serious harm, the MCS should promptly take either/both market- and FSP-level actions. Contract analysis findings often complement other evidence (e.g., analysis of consumer complaints, mystery shopping, meetings with FSPs). Findings on market-level harm or potential serious harm may require actions that affect a whole sector or multiple FSPs. These could include:

- Proposing a change to the regulation or issuance of a supervisory or policy note affecting all FSPs that offer similar products. For example:

- A direction to adjust an APR’s disclosure format

- Inclusion of a standardized disclosure of the phone number of an FSP’s complaints handling unit

- Prohibition of a particular exclusion from insurance coverage

- Addition of a certain clause to the list of prohibited contractual clauses (e.g., clauses that exempt FSPs from responsibility for data breaches)

- Less common but more serious actions such as a complete ban on a product considered harmful (e.g., phone-based contracting of payroll loans being banned in Brazil based on market monitoring findings)

Back to top ↑

Limitations of this tool

- Supervisory powers. Collecting contracts may not be an option. MCSs may lack the power to impose contract reporting, especially where regulation requires FSPs to disclose standard-form contracts on their website. In this case, web scraping may be a substitute to reporting. An MCS may also negotiate voluntary reporting of standard-form contracts.

- Data protection issues. Data protection legislation may prevent some MCSs from collecting actual contracts for market monitoring purposes. To overcome these restrictions, an MCS could require FSPs to anonymize contracts prior to reporting. However, this may increase compliance costs for the FSPs. Anonymization could also make it impossible for the MCS to complete certain analyses, depending on whether client particulars such as gender and address have been anonymized.

- Resource intensiveness. Contract analysis is time-consuming because it mostly involves manual activities such as document retrieval, classification, analysis, and reporting. In addition, while contract analysis requires a high level of specialization and legal expertise, it may become repetitive over time and demotivate staff.

- Limited depth. MCSs are often unable to cover the entire universe of standard-form contracts available in the market and all regulatory requirements that apply to them—let alone the same details for actual contracts. As a result, an MCS may resort to sampling, which can carry the risk of failing to spot problems.

Many MCSs are looking to address the shortcomings of contract analyses by investing in suptech—particularly solutions that at least partially automate the process of retrieving, classifying, and analyzing contracts, and reporting and organizing findings. If an MCS already has a database for standard-form contracts and a rules repository, it can more easily apply technology to sweep the database and analyze contracts based on its rules repository. Analysis may range from simple compliance checks (e.g., “yes” or “no” determinations) to question-based approaches (e.g., “Has the APR been disclosed?”, “Is the client address included?”, “Is the customer service number disclosed?”) to sophisticated analyses of contractual language to identify hard-to-understand or misleading terms.

The core technology is natural language processing (NLP), which translates human text into computer language. More sophisticated tools use machine learning to go beyond a document analysis that is solely based on a straightforward set of rules. Machine learning improves a rules repository by developing new and constantly changing internal “rules” in the form of algorithms. This is possible when a suptech tool is fed a large volume of previously completed human-based contract analyses, and when each new analysis validated by human analysts provides feedback to the constantly changing algorithms.

Banco de Portugal piloted a suptech tool in the context of standard-form contract analysis and is moving toward its full-scale implementation in 2021. This case illustrates the power of suptech to optimize the use of supervisory staff. Banco de Portugal expects the tool will save 8–16 months of staff time per year, allowing staff members to apply their intellectual capacity to more complex analyses.

Back to top ↑

Other resources

- SupTech Tools for Market Conduct Supervisors (FinCoNet 2020)

- A Roadmap to SupTech Solutions for Low Income (IDA) Countries (World Bank 2020)

- The Next Wave of Suptech Innovation – Suptech Solutions for Market Conduct Supervision (World Bank 2021)

- Regulatory Sandboxes: A Tool for Fostering Financial Innovation - Collection (CGAP)

- Implementing Consumer Protection (CGAP 2013)