Financial Inclusion is Key to Fulfilling the Promise of Platform Work

A growing class of platform workers and sellers are digitally savvy and literate, yet because they are largely from low-to-middle income communities they remain financially excluded and unable to reap the opportunities and mitigate the risks of platform work. As platforms transform the nature of work in emerging markets, embedding financial services for workers into platforms is pertinent and could point to pathways for including the greater informal economy as well.

In the years leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic, digital platforms that mediate the exchange of goods and services had been steadily growing across emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs), attracting a diverse group of individual workers and micro-businesses searching for higher incomes and larger customer bases.

With the lockdowns came paradoxical effects – on the one hand, “at-home workers” fueled growth of e-commerce and deliveries, aiding livelihood generation for platform delivery workers and microenterprises, albeit amidst unprecedented challenges. On the other hand, services like taxis, home-cleaning and other home-and-personal services came to a grinding halt, rendering many without a livelihood overnight and highlighting the same precarity to this new form of work as informal workers have experienced historically.

Platforms are slated to continue their growth; however, the pandemic has only further highlighted the growing sense that with new opportunities come new risks and uncertain futures for workers and sellers pursuing these new types of livelihoods.

CGAP’s research with platform workers and sellers in five EMDEs revealed that almost everyone entering the platform ecosystem in search of a better livelihood are literate and digitally savvy, but beyond basic bank or mobile money accounts, most are financially excluded or underserved, leaving them less able to leverage the opportunities and mitigate the risks inherent in this work. Here is how a lack of financial inclusion inhibits this group.

Workers and sellers cannot leverage growth opportunities due to lack of capital

A worker’s trajectory in the platform ecosystem is determined by their skills and prevailing gender norms that place them in specific types of platform work – whether ride-hailing, deliveries, e-commerce or e-lancing. To grow in an area of work, access to capital can be a gamechanger, allowing workers to buy better equipment and tools or train in new skills and techniques, in turn commanding higher pay for the same job or entering higher paying platform niches. For instance, a hair stylist could offer hair color services. An e-lancer could bid for bigger, more prestigious work that involves hiring a team. A ride-hailing driver could own his own car instead of paying rent on it, and perhaps even eventually build a fleet of cars for hire on platforms. However, such access to credit and investments is extremely rare among platform workers today – only 16 percent used loans to support their platform work.

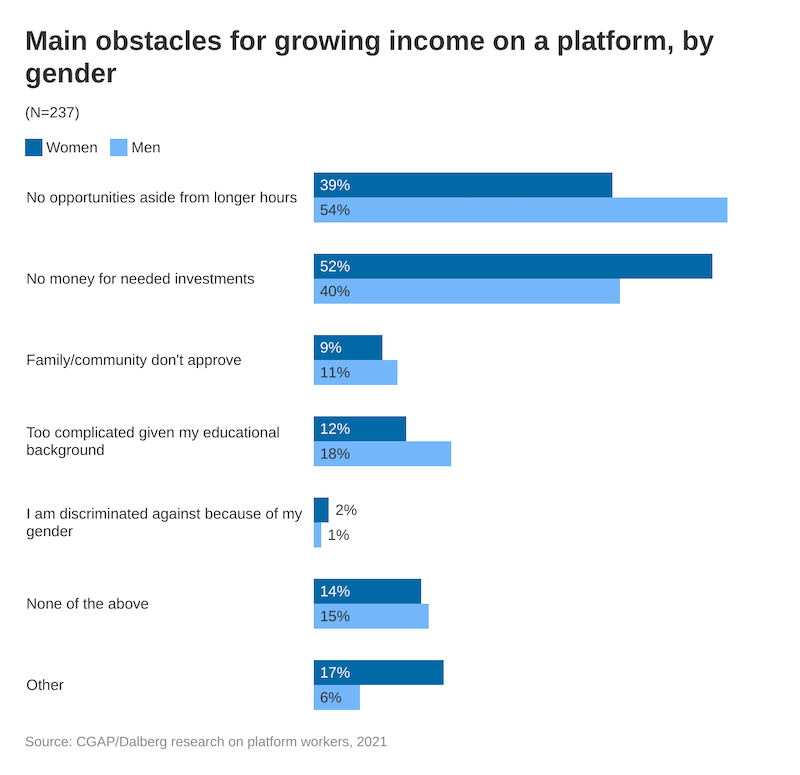

In fact, 52% of women and 40% of men surveyed in our research said they did not have access to money for investments that could help them grow their income on platforms (see Figure 1). Such access is particularly challenging for women sellers just starting a business. As Archie Osongo, a Kenyan small business owner that participated in our research said, “I would…maybe get a loan from a bank that’s giving a low interest rate. But I didn’t have security for it, so I didn’t manage to get it from them.”

Monthly money management is challenging amidst recurring and unpredictable expenses

Workers, most of whom come from the informal economy, are used to liquidity gaps between paychecks, but the growing unpredictability of platform incomes adds to this challenge. Understanding how much income they might earn in a pay cycle involves complicated calculations around peak and low hours and incentives — more so if they work across several platforms. Platforms rarely help workers understand earnings through tools within the app that could help them make sound financial decisions. Through past research with low-income communities, we know that medical emergencies (both large and small) are common and can lead to significant economic instability. Despite this fact, only 7% of male and 20% of female platform workers and sellers said they have insurance that would support such needs. Further, the tools workers use (i.e., cars, equipment, cell phones) are rarely, if ever, insured, leading to expenses, halting of work and immediate wage loss.

Though less visible, there is more digitalization of work happening alongside platforms

Aside from large platforms, which are some of the biggest companies in existence globally, other avenues for the digitalization of work are also afoot. Many workers we spoke with had also enrolled with digital labor aggregators that supply labor to large platforms, businesses and private customers. In addition to selling on e-commerce platforms, some sellers conducted digital sales and marketing on social media and chat platforms like Instagram and WhatsApp. Smaller, more local platforms are also emerging that systematize different aspects of sales for artisans and small sellers.

So, with the digitization of work taking place in various ways through platforms, aggregators, and other avenues, the size of the platform economy in EMDEs (while still much smaller than the total informal labor market) may be larger than publicly available numbers suggest. This means that embedding financial services in this digital ecosystem holistically requires participation and partnerships within a wide group of actors. Solutions designed purely for one kind of worker or one type of platform may not work as well as those designed for the broader ecosystem. It also means that if financial services are successfully embedded in this digital ecosystem, they could, with some effort, also be made applicable to the larger labor market.

The pandemic also made clear that when big public shocks related to public health, climate change and economy fluctuation arrive, platform workers are no better protected than others in the informal and semi-formal economy. Like informal workers, they continue to exist outside the traditional employer/employee relationship, yet are above the threshold to qualify for government benefits. In the pandemic, several platforms did provide their workers support, but they rarely proved adequate. Once again, the growing size of this cohort with recent access to internet connectivity and bank or mobile money accounts, but without the full support of formal finance, presents an opportunity for testing new kinds of public safety nets that connect workers’ digital data identities on platforms with a suite of services that can range from savings deposits and insurance in stable times to short-term loans and advances against term deposits to cope with sudden shocks. However, this idea remains largely theoretical, and the public sector’s engagement with platforms on worker welfare has been limited in EMDEs.

Today, much of the potential of using the platform ecosystem to financial include platform workers is unrealized, both because of the nascency of the ecosystem and the lack of insight on what innovations and market coordination are needed. In the coming weeks, experts from the platform livelihoods team at CGAP will unpack various facets of our extensive research with platform workers, platforms and FSPs to describe 1) the types of innovations that will be valuable for workers, 2) key challenges to extracting the value of platform work data responsibly, and 3) reaching marginalized groups of platform workers, especially women workers.

This blog is part of a broader CGAP effort over the coming months to work with platforms and financial services providers to pilot new financial solutions for this small but fast-growing segment of the economy that is transforming livelihoods opportunities for low-income communities. Visit www.cgap.org/platform-workers for more information, and see our paper and reading deck for a deeper dive into the ideas introduced here.

Add new comment