Inclusive Finance in Fragile Countries: Advancing a Vital Agenda

With 80% of the world’s poorest expected to be living in fragile countries by 2030, fighting poverty means addressing fragility. This is why fragility has become a priority on the international agenda in recent years, and more so since the COVID-19 pandemic reversed decades of progress in fighting extreme poverty. Yet, .

What is fragility?

Like poverty, fragility has multiple interrelated dimensions. According to the OECD, fragility refers to the "combination of exposure to risk and insufficient coping capacity of the state, systems and/or communities to manage, absorb or mitigate those risks." It not only impedes a country’s ability to deliver equitable and sustainable development, but also renders a country more prone to conflict, which tends to escalate when basic social, economic, legal and security services are weak or absent.

Fragile countries have distinct characteristics. First, large illicit financial flows and net capital outflows — estimated to exceed the inflows of both official development assistance and net foreign direct investments — lead to the depletion of governmental resources and prevent the provision of strong public goods and infrastructure. This, in turn, requires almost half of official development assistance to be used for humanitarian purposes or peace financing.

Second, 70% of fragile countries have a tax-to-GDP ratio below the minimum 15% needed to finance basic services. This indicates lower economic development and less equitable distribution of wealth. Factors such as corruption; significant informal employment; formal productive sectors, including natural resources, that are dominated by a small number of economic and political elites; and inefficiency in sectors such as agriculture all contribute to this low ratio.

Third, gender inequality is exacerbated in fragile countries. In times of crisis, women are more likely to lose livelihood sources due to responsibilities of caring for children and the elderly, experience displacement and have their education interrupted.

Poverty rates and financial exclusion levels tend to be higher in fragile countries than in non-fragile countries. The financial sector often remains underdeveloped in fragile countries. Although informal financial services are widely used and trusted, the number of formal financial service providers (FSPs), including commercial banks, microfinance institutions, insurance companies, and mobile money agents, are significantly lower than in non-fragile countries. For example, IMF FAS data shows about eight commercial bank branches per 100,000 adults in fragile countries, compared to 22 in non-fragile countries. A notable exception is the number of credit unions and cooperatives, which is higher in fragile countries, with roughly 2.5 times more branches per 100,000 adults.

The weak FSP capacity in fragile countries is generally due to lack of competition, non-existent or low-quality resources, low operating capital, out-migration and the absence of a conducive regulatory environment. It can drive illicit finance and weigh on correspondent banking relationships, many of which have been terminated in recent years due to perceived or actual compliance concerns, thereby disrupting or increasing the cost of financial services. In light of these supply-side limitations, it is not surprising that access to formal financial accounts, savings, credit and funds runs lower in fragile countries. Based on a CGAP analysis of the Global Findex data, formal account ownership in fragile countries is only half of that found in non-fragile contexts (36% vs. 71%, respectively). Women are 38% less likely to have a formal account compared to women in non-fragile countries and 11% less compared to men in fragile countries, signaling a need for gender-intentional financial system development.

Access to credit is also limited, with only 8% of adults having borrowed from a financial institution in fragile countries, compared to 14% in non-fragile. And there is a 10% discrepancy in individuals who could come up with emergency funds in fragile and non-fragile countries — at 48% and 58%, respectively.

Notably, mobile money account ownership is 8% higher in fragile countries, indicating a potential to reach individuals with meaningful services. However, the number of active mobile money agent outlets per 100,000 adults is more than six times lower in fragile countries, suggesting more investments (e.g., distribution networks) are needed to realize the potential of digital financial services (DFS).

How can funders play a bigger role in highly fragile countries?

Based on OECD’s fragility framework and severity ranking, CGAP identified the 23 most highly fragile countries with active financial inclusion commitments in 2019, home to approximately 10% of the global population. We then leveraged the 2019 CGAP Funder Survey data to analyze the role financial inclusion donors and investors are playing in these countries.

Only 9% of active single-country financial inclusion projects were implemented in these countries in 2019, totaling $2.9 billion and representing 8% of total active commitments. These are particularly low numbers given the scale and consequences of continued exclusion in fragile environments, especially since funding is concentrated in a handful of countries. However, the positive news is that financial inclusion projects tagged to women are proportionally more common in highly fragile countries (15% compared to 10% globally), rightly tackling women’s greater exclusion in these contexts.

Unsurprisingly, the predominant form of funding is grants (36% compared to 16% globally), which may reflect the earlier stages of market development, associated needs and perceived investment risks. Like global funding trends, most funding in highly fragile countries supports microfinance activities, primarily through direct funding to microfinance institutions, funding to microfinance investment vehicles (MIVs), and support to strengthen the policy environment or build capacity at the retail or market level.

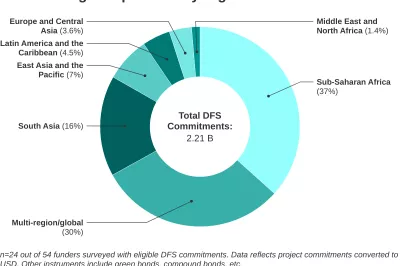

Only 5% of all DFS commitments went to highly fragile countries, proportionally less than the 8% share of total funding for financial inclusion. Possible explanations for this low figure include the earlier stage of DFS development relative to microfinance, DFS potentially being commercially viable and not requiring development funding, and the complexities of working in fragile countries for development funders, which range from data gaps to intricate political dynamics and instability.

The COVID-19 pandemic and recent economic crises have impacted funders and recipients alike, introducing new dimensions of fragility in communities around the globe and simultaneously revealing fragility in funding flows themselves. Many funders are dealing with budget fluctuations and shifting priorities that will impact the aid ecosystem for years to come. This changing landscape will impact the fight against poverty, and fragile contexts stand to be left behind if funders are not willing and able to engage proactively.

. To unpack the multiple interrelated dimensions of fragility, CGAP is delving into the topic: is it possible to build an inclusive finance ecosystem if the basic causes of fragility are not effectively addressed? If so, how can inclusive finance be built and strengthened in such countries? And what would be the role of development finance? Exploring these questions is an important next step for the funder community in its fight against poverty, to collectively ensure low-income populations are better equipped to manage crises and shocks.

Add new comment